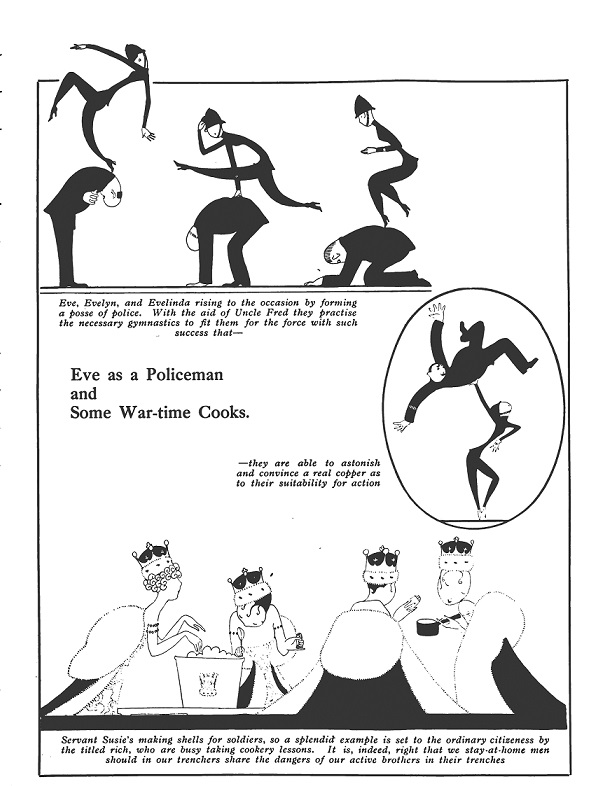

The early twentieth century can be considered the beginning of the golden age of illustration. From James Montgomery Flagg, to Charles Dana Gibson, to Nell Brinkley, magazines and advertisers and newspapers attracted and delighted millions of consumers using eye-catching graphics. On the other side of the pond, illustrators like Leslie Ward, Beatrix Potter, and Arthur Rackham, to name a few, brought England’s luminaries–and nature–to the masses. The popularity of witty illustrations didn’t end during WWI; in fact, it grew, particularly when paired with an unforgettable character. Britons of the Great War era found this in “Eve.” Created by Olivia Maitland Davidson in early 1914, the character was a “chatty, light-hearted society girl, flirtatious, vivatcious, fun loving, fond of fashion and ‘frivol’ (frivolity).” 1 Illustrated by Anne Harriet Fish, “Eve” harkened back to Aubrey Beardsley, but with an insouciant, feminine flair. Between the two talented women, “Eve” took readers’ minds off the grimness of the war with her exploits and adventures, and, as Luci Gosling argues, acted as a “tour guide to Great War Britain” through her letters to her best friend Betty.

August 5th, 1914.

Oh, Betty, so it’s really, really war ! It’s been the awfullest week-end … of course Cowes and every other plan blown to the winds utterly. One has just waited — your Eve must be at the heart of things, as well as of men! And here in London these last days the very heart of the world has seemed to beat. They were so vast, so far-reaching, the issues facing

England, our England,

one has felt as if we stood on the edge of a precipice.

Everything else has seemed dwarfed. With such great affairs at stake, even one’s own small personal interests, generally so important, haven’t mattered; they’ve been engulfed and swallowed up in the great cataclysm. No one’s cared to go anywhere or do anything, or make any kind of plans. We’ve been like a people suffering from shock, and even the masses didn’t, thank goodness, maffick over the Declaration of War — the nearest they got to it being to collect in large clumps round the Palace and at Westminster and cheer Majesties, Ministers and anyone else who turned up.

Nothing’s been talked of and nothing thought about except war, and all war may mean to this little island we all, at the bottom of our unexcitable English hearts, adore so passionately and so devotedly. I suppose truly and clearly to realise the real depth and size and nature of this most awful European convulsion — that isn’t possible But it’s been a nerve-shattering two weeks. We were all for peace, and we came to war. Truly a mad world, my masters.

Yours sadly,

Eve.

—

October 21st, 1914.

Dearest Betty,

What’s been christened ” the Antwerp week-end ” has been a stern chastener of our spirits. And the treachery in South Africa, on top of the fearful wearingness of no news at all from the Front, fairly put the lid on it.

Still, here in London, save for the darkness, you’d even now hardly know we were at war — not from any outward and visible signs, anyway. The Dansants are still going merrily in Bond Street and elsewhere, you just can’t move at the Savoy for the dancing supper crowds, and ” There wasn’t a seat in the house,” I heard, on the very day that “impregnable” Antwerp fell, at a theatre where a German musical comedy is being run by a Hun proprietor.

But at Ostend, such is the rush of our wounded, they say they’ve been performing operations without chloroform — the supply of everything, doctors and nurses as well as medical necessities, is quite unequal to the demand. The W.O., I suppose, is doing its best, and everyone says the heroism of the R.A.M.C. in the field is simply wonderful. But it’s all been a million- times-bigger thing than anyone ever imagined, and our poor men, of course, are the sufferers for the muddle.

And meantime — well, really, you know, Betty, I’m not sure there isn’t a limit in war-time to the Business-as-Usual, Everything-as-Usual idea. Life must go on, of course, even in the midst of the dreadfullest of wars. But it’s really seemed hardly decent — the rush to Scotland, the crowd at the Cesarewitch, and the swarms shopping, theatreing, motoring and feeding just as usual everywhere, while over there it’s all we can do to keep our end up against the Hun and things are so awf’ly critical and difficult. It’s a much more in-the-picture, tho’ a rather touching sight — all those hundreds of thousands of our civilian men drilling away so intently in all the squares and open places everywhere. Most are hardly even in uniform yet, the rush on the factories and shops has been so tremendous. But they’re all tryin’ so very hard to be soldiers, poor dears, that sometimes they nearly make me cry, they do.

Doesn’t make things ‘zacly easier for them, you know, that such a lot of the men who rushed to the colours are the kind that aren’t used to discomfort. Roughing it in camps and sticking it in fearf’ly leaky huts is a stiff strain on the quality of patriotism, and some poor dears who’ve never slept before in anything but fine linen I’m told find the frequent liveliness of the army blanket not the least of life’s new crosses. But they’ve done a good five months’ work in five weeks, they say, such is their martial ardour, at which rate we’ll really have an army by Christmas, won’t we? And, ‘cording to the optimists, it’s just about by that date, too, you know, that we’ll also be starting on the long, long road to — no, not Tipperary, but Berlin.

Women, too, of course, are really getting through quite a lot of war- work, and “comforts” are going out to the troops and the Navy in such billions they say the ports are blocked with ’em. In the race to be charitable, seems only the motor-car owners aren’t quite coming up to the scratch. Cars are simply dreff’ly wanted in France, ‘specially for the wounded. But walk down Piccadilly any fine morning or afternoon and you can still count in hundreds the cars de luxe carrying ladies de luxe to nowhere in particular.

Yours, nearly dead knittin’,

Eve.

—

March 1st, 1916.

Betty mine,

You wouldn’t b’lieve how womanly we’re getting ! Work-parties are the rage. And what ‘muses me is how the winsome war-workers always bind their heads up a la Red Cross sister and garb themselves that way, too. Very becoming, you know ; and I s’pose head-dress and uniform do help after you’ve sewn about the fifteenth shirt for soldiers. But they do say that gags ‘d be really more useful than anything. The talk that goes on in those work-rooms . . .

Rather a blow, by the way, when Lord Grenfell at the Horticultural Society’s Show last week said we simply must grow vegetables, and didn’t even mention flowers. Gardening’s been the last cult we thought the old war ‘d interfere with — so innocent and healthy and all that, you know, and so smart.

The Very Best people are all simply mad on Japanese gardens and sunk ones and water ones and pergolas and rose – walks and herb – runs and lavender hedges and all the rest. The talk of the town’s all of money, money, money; and we’re watchin’ out fearf’ly interested to see how the new War Savings Committee is going to start in to make people save ‘cos of the “grave condition of national finance.” Which even that most irrepressible of optimists, the P.M., now finds not only a serious but a ” staggering ‘ burden. There’s at least one millionaire among ’em, and a few more not eggzacly paupers, you know — Lord Curzon f ‘rinstance, and the Archbish of Canterbury, and Lord Burnham and Lord Balfour ; and p’r’aps to the mere outsider it doesn’t look as if domestic thrift’s quite the sort of subject for these kind of people to give advice on to those who support life on £2 a week as against their £200 or so.

Still, there certainly is quite a lot of economy goin’. Closing down the houses you don’t want and cutting down the courses at dinner f ‘rinstance, and talking about giving up your maid. But even then I s’pose we’re still left with lots more luxuries than’s really necessary to support life. There’s a story the Germ women are selling their wedding-rings to pay for tho war. Haven’t heard of anyone goin’ to any lengths like that here, have you? But really, you know, we get a bit discouraged at times. Did you hear of that canteen secretary person who wrote to tho papers the other day to say it ‘d be much better if the stream of ” fitful, irresponsible, capricious and easily offended lady workers “would do their own house work and so set free the real ivorkers? Great mind to take along Tou-Tou to bite her, I have.

The crocuses are all blazing away on the grass in the Park, and the trees bursting into bud, and the birds chirpin’ — another spring and still that awful war ! Tou-Tou and me we’re fair fed up with it we are. Really, if they ever do fix up about that new Air Minister they say we simply must have, I think I’ll have to get him to fly with me. There must be somewhere where there isn’t a war !

Yours flightily,

Eve.

—

April 10th, 1917.

Dearest Betty,

So America’s really ” in ” at last ! Well, well . . . Better late, etc., but we won’t be able to call her ‘zacly a hustler any more, will we? Tho’ they do say that the U.S.A. Navy has really been quite looking forward to some fun some time. Fightin’s after all the fashion, you see, and for God’s own partic’lar country to be out of the ” movement ” for nearly three years . . . But now they have come, makes you quite breffless, the huge numbers the country that was too proud to fight seems to have to juggle with. Fifteen to twenty millions of men of military age ready to draw upon straight away. , . . Think of it !

Talk about some of us ” enjoying the war.” In this little land that we love we’ve known anyway a few war trials — our men leaving us every day and every day returning hurt and broken, or not returning ever; air raids and bombardments and conscription and all the rest. And never even at our gayest have we risen to such heights of revelry as they have in New York since Europe went to war and poured out her millions in millions.

Dancing’s the great craze, led by the Vernon Castles ; and the fearful expense of everything doesn’t in the very least matter ‘cos everyone’s got money to blow.

Here, so set is Sir Frankie Lloyd upon the primrose path of purity as the proper place for the modern soldier-man to walk in, that really we look like becoming respectable to tedium, and deader than the dodo soon will be our latent passion for dancing in the public places rag-time from Kentucky, Paris and Broadway. But the truth is, you know, as even the fluffiest are discovering, there just isn’t time for anything much these days ‘cept for battle-fighting. ” The strength of the brute’s stupendous even now,” a letter from the thick of it’s just told me. “Don’t you listen when they tell you the Hun’s nearly done. Done ! Not a bit of it. Much more like getting a fresh wind.”

And this Russian Revolution business — what does it all mean, and what’s it the beginning of, and how will it affect us? More effort, more treasure poured out, more everything for poor dear England, I suppose.

A poor life this if, full of care,

We have no time to stand and stare,

sings W. H. Davies, poet. But it’ll have to be a “poor life,” I’m afraid, for once again the great man-power question’s the topic. They say if they can’t get enough from the rejected and Whitehall and the trade unions they’ll really have to put up the age-limit to forty-five and even fifty. Which, of course, the ‘thorities most dreff’ly don’t want to do. It’s this lot that pays most of the taxes, you see, and with a seven or eight million a day war to keep goin’, s’pose we do want a few businesses turning the money out.

They say, by the Way, that theatres are getting it a bit in the neck under the war regime. But I haven’t noticed any slump, tho’ really, you know, if revue does get soon to the shut-eye stage you couldn’t be frightfully surprised. No one’s said one funny thing or sung a pretty one at the last fifty I’ve been to. Made me almost agree with Mr. Bernard Shaw on the subject — ” The effect of revue is to reconcile me to death “; tho’ I wouldn’t like to be quite as drastic as Augustus John, who says, ” All are rotten. I hate ’em.” Nicely dined and wined, I can always do with anyway an hour of ’em, or say half an hour.

Yours While the Great Big World Keeps Turning,

Eve.

—

— The Letters of Eve by Olivia Maitland-Davidson

- Great War Britain: The First World War at Home by Lucinda Gosling. ↩

“We were all for peace, and we came to war. Truly a mad world, my masters”. Yet we cannot even blame Eve for misreading the world situation in August 1914. Everybody thought that war would be averted, or at least that the soldiers would be back by Christmas 1914. What a miserable time, that was 🙁

Definitely.