Though the educational acts passed after the 1870s provided free, mandatory schooling for both sexes, girls were not only educated differently than boys, but they had to fight for schooling beyond the grammar level. Even after the foundation of famed women’s colleges such as Somerville, Girton, or Lady Margaret Hall, and the opening of universities to women, they still grappled with proving their relevance in an era where a woman’s sole purpose was to marry and tend to her home. Yet, pioneers such as Dorothea Beale and Frances Buss marched on with the foundation for female education laid in the 1830s-1860s, and became synonymous with the topic of womens’ higher education.

By the Edwardian era, there were twenty-one girls’ public schools, teaching approximately 5,000 pupils, and even more girls’ high schools (and some co-educational secondary schools) in existence across the whole of Britain. The average curriculum balanced the typical feminine accomplishments such as sewing, cooking, housewifery, and infant care and the “harder” subjects such as chemistry, mathematics, and languages, and most girls colleges featured a separate institution for the training of teachers. In fact, the push for higher education for women went hand in hand with the increase in education for the lower and working classes since in the late 19th century teaching had become a woman’s profession (those poor governesses notwithstanding).

In tandem with the rigorous and challenging curriculum at girls’ schools was the formation of ladies’ colleges at the university level. Miss Beale, the formidable headmistress of Cheltenham Ladies’ College, spearheaded the founding of St. Hilda’s College at Oxford in 1893, determined as she was to continue her crusade to educate girls who would go on to change the world. St. Hilda’s joined Somerville, St Hugh’s, and Lady Margaret Hall as pioneer women’s colleges at Oxford, and its sister schools at Cambridge–Girton and Newnham–to change society’s minds about women’s education (though not without a considerable battle against the jokes and harassment at the expense of female students). Nevertheless, these pioneer headmistresses and students soldiered on, breaking the glass ceiling in many traditionally male fields, and earning respect for their achievements and mental prowess in their own right.

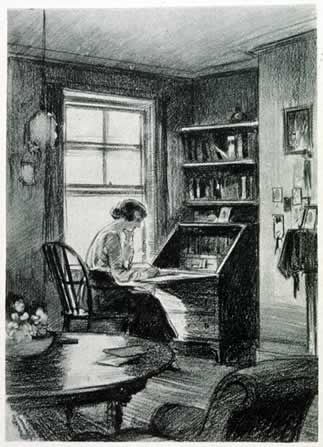

Unfortunately, upper class and aristocratic women were barred–by social norms–from these great educational strides and remained as poorly educated as their Regency and Victorian forebears. For them, a governess who taught the rudimentary topics of reading, writing, and arithmetic and the social graces, with a varnish of sophistication provided by a few months in Germany or Switzerland before their debut were good enough. Some upper class and aristocratic women furnished their own self-education, courtesy of their family libraries, but since they were supposed to worry more about their court curtseys and small talk, and their reading was strongly censored, quenching the thirst for education could be difficult. Nevertheless, these women gained a “hands-on” education in politics, hostessing, and managing estates, and though most considered their “power behind the throne” as the basis of their anti-suffrage stance, they proved that an educated and intelligent woman was the new norm for the modern age.

Further Reading:

Girls Growing up in late Victorian and Edwardian England by Carol Dyhouse

The Victorian and Edwardian Schoolchild by Pamela Horn

The Public School Phenomenon, 597–1977 by Jonathan Gathorne-Hardy

The Edwardian Lady by Susan Tweedsmuir

Education of Girls and Women in Great Britain by C.S. Bremner

The Renaissance of Girls’ Education in England: A Record of Fifty Years’ Progress by Alice Zimmern

I’m reading a book from 1914 right now with a female doctor in Germany. Do you know if Europe was ahead or behind the US when it came to letting women into universities?

Ahead, surprisingly (though I believe France was much less progressive). I’ll have to look at my sources, but I recall an Italian university that opened psychiatry courses to female students.

Great topic!

Free, mandatory and equal education for all youngsters came in during the 1870s, yet we have to ask if the legislation worked. How old did a child have to be, before he could leave school and move into the labour force? What happened if working class youngsters were sent down coal mines or into textile factories – were their parents pursued?

I am trying to differentiate between gender and social class issues here.

An article in Slate delineates similar activities in contemporary France: http://tinyurl.com/98hj2mc

or

http://www.slate.com/articles/double_x/doublex/2012/09/having_it_all_in_belle_poque_france_how_magazines_remade_the_modern_woman_.html

There was an Italian woman who received a degree in the 17th century and women had also been teaching at Italian universities,.

Great overview, thank you. Dorothea Bealen the headmistress mentioned was appointed headmistress at the age of 27 and was also a great suffragist.

Thanks for the link to the Slate article, NJ Gill, it was a very interesting read.