When Sophia Smith made plans to bequeath her fortune to the foundation of a women’s college in the sleepy town of Northampton, Massachusetts, she laid the foundation for one of America’s premiere women’s colleges: “1) the educational advantages provided by it would be equal to those afforded by young men in their colleges; 2) Biblical study and Christian religious culture would be given prominence; 3) the cottage system of buildings, or homes for the students, instead of one mammoth central building, would prevail; 4) men would have a part in the government and instruction in it as well as women, ‘for it is a misfortune for young women or young men to be educated wholly by their own kind.'”

After Miss Smith’s death in 1870, her estate, appraised at $500,000, went almost entirely to the college for which she had designed it, and in September of the following year, the first building acquired by Smith College was purchased. A committee was formed to select a president for Smith, and Reverend Lauremus Clark Seelye, LL.D., was chosen. This careful, intelligent man enhanced Sophia Smith’s vision for her women’s college; after surveying women’s colleges and universities at home and abroad, and consulting with the leading educators of the time, he determined that Smith should have no preparatory department connected with it and decided that it should be a college where young women would have superior opportunities for increasing their education. Up to the founding of Smith, no other college for women had been founded without a preparatory department, none had required Greek for entrance, and the majority of them demanded little more, and often less, than that accomplished in the best secondary schools. But Seelye was determined that Smith be different, and in the summer of 1875, College Hall, the first academic building, was finished and dedicated, and at a quarter to nine, September 9, 1875, Smith College opened at morning prayers with four residing teachers and fourteen students. From then on, Smith College devoted itself to excellence in women’s higher education, and began to carve its own niche amongst its “seven sisters.”

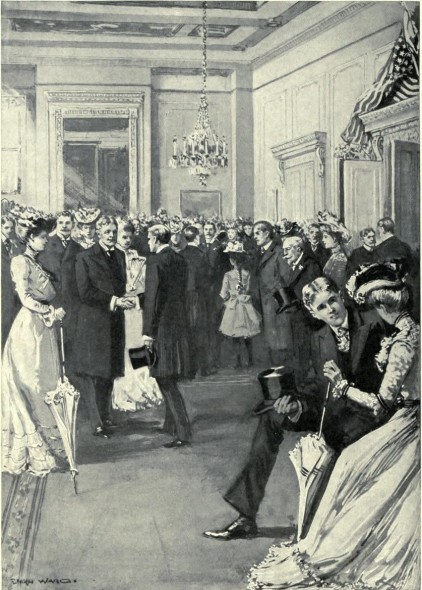

The college year at Smith opened with a dance known as the “Freshman Frolic,” then in October, came the reception given by the sophomores to welcome the entering class. A new girl would be escorted to this occasion by an upper class partner, who, in addition to filling out her dance card and sending her flowers, saw to it that the freshman met the right person for each dance. The upper class partner entertained the freshman during refreshments and then saw her home. A dance of the same sort was given by the junior class members as a farewell to the senior class. Other important events were Mountain Day, where everyone took the day off for outdoor excursions, and Rally Day, which was held informally in the mid 1890s, and was celebrated in the Spring.

Since there was no preparatory department attached to Smith, its curriculum was vigorous and thorough, “a year’s work being required of all students in certain specified studies. A certain number of papers was to be submitted to the English department for criticism every year in which the requirement in English was not taken. All required studies except Philosophy must be taken in the first two years. Each student must pursue a main study which shall consist of related three-hour courses, taken consecutively through the Junior and Senior years, and based, so far as is specified by the several departments, upon preliminary work of the earlier years.” Physical training was also required, and each member of the first and second classes was required to take gymnasium work for half hours a week from November 1st to the spring recess. Juniors and Seniors were required four periods of exercise a week of not less than one hour each from October 1 to June 1. Neither were considered a hardship for Smith’s students, particularly the latter, when a mania for basketball and (field) hockey swept through women’s colleges in both America and England in the 1890s.

Tuition in 1905 was $100, and room and board, $300 a year, which was moderately expensive, especially since it was not yet fashionable for the daughters of extremely wealthy men to attend college. To help with the expenses, Smith not only had a many, many scholarships for students, but a Student’s Aid Society, which assisted those who lacked the means to finish their education by offering loans without interest to needy and worthy students of the three upper classes, allowing them three to five years for the payment.

Though women’s colleges in America later followed Smith’s lead in abolishing preparatory departments and increasing the rigor of their curriculum, Smith nonetheless remains dedicated to producing women of intelligence and achievement, and of broad outlook.