Margot Asquith (1864 – 1945) was born to Scottish industrialist Sir Charles Tennant and his retiring wife Emma. As the sixth daughter out of eleven children, Margot’s upbringing was rather wild for the day, and the high-spirits and independence of her and her sister Laura entranced a number of people upon their entry into late Victorian high society. In her autobiography, published in four parts in the early 1920s, Margot reflects upon her upbringing, marriage, and position within The Souls. In the following passage she describes her education before making her debut, which was rather typical of upper-class and aristocratic young women of the 1880s.

ALTHOUGH I did not do much thinking over my education, others did it for me. I had been well grounded by a series of short-stayed governesses in the Druids and woad, in Alfred and the cakes, Romulus and Remus and Bruce and the spider. I could speak French well and German a little; and I knew a great deal of every kind of literature from Tristram Shandy and The Antiquary to Under Two Flags and The Grammarian’s Funeral; but the governesses had been failures and, when Lucy married, my mother decided that Laura and I should go to school.

Mademoiselle de Mennecy—a Frenchwoman of ill-temper and a lively mind—had opened a hyper-refined seminary in Gloucester Crescent, where she undertook to “finish” twelve young ladies. My father had a horror of girls’ schools (and if he could “get through”—to use the orthodox expression of the spookists—he would find all his opinions on this subject more than justified by the manners, morals and learning of the young ladies of the present day) but as it was a question of only a few months he waived his objection.

No. 7 Gloucester Crescent looked down on the Great Western Railway; the lowing of cows, the bleating of sheep and sudden shrill whistles and other odd sounds kept me awake, and my bed rocked and trembled as the vigorous trains passed at uncertain intervals all through the night. This, combined with sticky food, was more than Laura could bear and she had no difficulty in persuading my papa that if she were to stay longer than one week her health would certainly suffer. I was much upset when she left me, but faintly consoled by receiving permission to ride in the Row three times a week; Mlle. de Mennecy thought my beautiful hack gave prestige to her front door and raised no objections.

Sitting alone in the horsehair schoolroom, with a French patent-leather Bible in my hands, surrounded by eleven young ladies, made my heart sink. “Et le roi David déplut á l’Éternel ” I heard in a broad Scotch accent; and for the first time I looked closely at my stable companions.

Mlle. de Mennecy allowed no one to argue with her; and our first little brush took place after she informed me of this fact.

“But in that case, mademoiselle,” said I, “how are any of us to learn anything? I don’t know how much the others know, but I know nothing except what I’ve read; so, unless I ask questions, how am I to learn?”

Mlle. De Mennecy: “Je ne vous ai jamais défendu de me questionner; vous n’écoutez pas, mademoiselle. J’ai dit qu’il ne fallait pas discuter avec moi.” (I’ve never defended questioning me, you do not listen, miss. I said that one should not argue with me.)

Margot (keenly): “But, mademoiselle, discussion is the only way of making lessons interesting.”

Mlle. De Mennecy (with violence): “Voulez-vous vous taire?” (Would you shut up?)

To talk to a girl of nearly seventeen in this way was so unintelligent that I made up my mind I would waste neither time nor affection on her. None of the girls were particularly clever, but we all liked each other and for the first time—and I may safely say the last—I was looked upon as a kind of heroine.

…On my arrival in Grosvenor Square I told my parents that I must go home to Glen, as I felt suffocated by the pettiness and conventionality of my late experience. The moderate teaching and general atmosphere of Gloucester Crescent had depressed me, and London feels airless when one is out of spirits: in any case it can never be quite a home to any one born in Scotland.

…[M]y father was too busy and my mother too detached for me to have told them anything. I wanted to be alone and I wanted to learn. After endless talks it was decided that I should go to Germany for four or five months and thus settle the problem of an unbegun but finishing education.

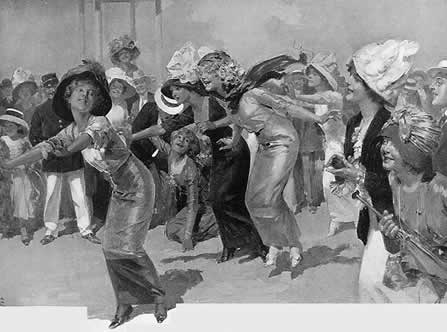

Looking back on this decision, I think it was a remarkable one. I had a passion for dancing and my father wanted me to go to balls; I had a genius for horses and adored hunting; I had such a wonderful hack that every one collected at the Park rails when they saw me coming into the Row; but all this did not deflect me from my purpose and I went to Dresden alone with a stupid maid at a time when—if not in England, certainly in Germany— I might have passed as a moderate beauty.

Frau von Mach kept a ginger-coloured lodging-house high up in Lüttichau-strasse. She was a woman of culture and refinement; her mother had been English and her husband, having gone mad in the Franco-Prussian war, had left her penniless with three children. She had to work for her living and she cooked and scrubbed without a thought for herself from dawn till dark.

There were thirteen pianos on our floor and two or three permanent lodgers. The rest of the people came and went—men, women and boys of every nationality, professionals and amateurs—but I was too busy to care or notice who went or who came. Although my mother was bold and right to let me go as a bachelor to Dresden, I could not have done it myself. Later on, like every one else, I sent my stepdaughter and daughter to be educated in Germany for a short time, but they were chaperoned by a woman of worth and character, who never left them: my German nursery-governess, who came to me when Elizabeth was four.

The Dresden of my day was different from the Dresden of twenty years after. I never saw an English person the whole time I was there. After settling into my new rooms, I wrote out for myself a severe Stundenplan (timetable), which I pinned over my head next to my alarm-clock. At 6 every morning I woke up and dashed into the kitchen to have coffee with the solitary slavey; after that I practised the fiddle or piano till 8.30, when we had the pension breakfast; and the rest of the day was taken up by literature, drawing and other lessons. I went to concerts or the opera by myself every night. I made great friends with Frau von Mach and in loose moments sat on her kitchen-table smoking cigarettes and eating black cherries; we discussed Shakespeare, Wagner, Brahms, Middlemarch, Bach and Hegel, and the time flew.