“You can always tell Suffragists by the way they are dressed,” pontificated an anonymous gentleman in 1913. “There’s that Mrs Chew, for instance – her hat’s never on straight!”

Stalwart suffrage campaigner Ada Nield Chew felt she had far more important concerns than a tidy appearance. Years later Ada’s daughter Doris commented, “How much easier it would have been today when she would not have needed to wear a hat!”

The truth is, hats, gloves, hemlines and handbags were all vital indicators of social status in the Edwardian era. Correct dress represented respectability. Women who stepped out of an acceptable female role were almost automatically branded unladylike, and satirised as unattractive.

If we view style of one hundred years ago, we find the fashions of 1914 quite alarming in their weight and constraints. The silhouette is long and sheath-like, moulded around form-fitting steel-structured stays and all-encompassing underwear. By contrast, the ideal of feminine beauty is dainty, delicate and generally pastel-shaded – hardly an icon of education, capability, or political power.

Some commentators did acknowledge the constraints of contemporary female fashion. “A man knows that if for a year he were to submit himself to the restraints which a woman puts upon herself, he would mentally, morally, and physically degenerate,” wrote a journalist in April 1914.

One Edwardian woman who certainly didn’t let fashion hobble her was martial arts expert Edith Garrud. Her ju-jitsu skills made a mockery of would-be muggers and over-assertive policemen alike. She kept wooden clubs in her hand-warming muff. If she sweetly dropped her handkerchief in the street it was as a prelude to a devastating bit of self-defence.

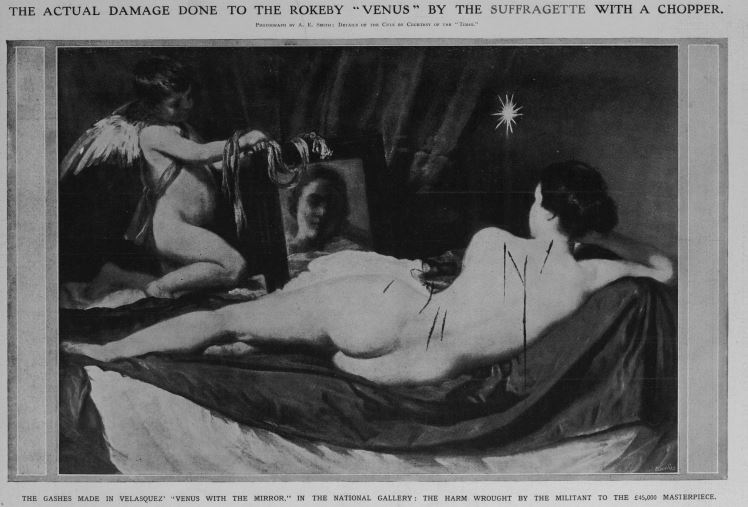

Undaunted by the contrast between the demands of appearance and the demand for political representation, both militant and non-violent suffragists learned to use their clothes as part of a series of battle tactics. For example, women who were dressed impeccably could pass without suspicion into public spaces or political meetings. Once in place they could whip chalk from their purses to scrawl slogans on pavements; they could pull chains from their handbags to secure themselves to railings, in order to have their say while someone searched for bolt-cutters. ‘Slasher’ Mary Richardson even concealed a small axe in her blouse sleeve, ready to attack Velasquez’s painting, the Rokeby Venus, at the National Gallery.

More generally, the tactic of adopting all-white ensembles in mass public rallies was hugely dramatic and it gave women a tremendous sense of solidarity. The militant Women’s Social Political Union went one step further and promoted specific WSPU colours. White was for purity, purple represented loyalty to the King, and green was for hope.

Militant suffragettes used clothes creatively to disguise themselves. Emily Wilding Davison made a fetching telegram ‘boy’ attempting to gain access to Parliament. Lady Constance Lytton took on the disguise of a working-class seamstress in order to highlight the prejudiced treatment of lower-class women in prison. On one glorious occasion, several WSPU suffragettes disguised themselves as their leader, Emmeline Pankhurst, in order to foil an attempt to arrest her.

Once women behaved in unladylike ways, chivalry from men was forgotten. The gloves came off on both sides. There were many reports of violence against suffragettes, from the minor outrage of torn clothes–or clothes stained with rotten eggs–to serious cases of sexual assault during suffrage rallies. Edith Garrud was employed to lead a team of bodyguards to protect WSPU speakers.

If arrested, female protesters were subjected to the further humiliation of having their respectable carapace of clothes quite literally stripped away and replaced with deliberately de-feminising prison garb.

By 1914 the green ‘hope’ of the WSPU banner was very much mingled with bitterness. Cat and mouse games between police and protesters, parliament and petitioners had reached an angry impasse. Militant terrorism was becoming increasingly shocking; peaceful petitions were still limited in success. With the declaration of war in August 1914 women found themselves facing different enemies, and poised on the brink of a veritable social and sartorial revolution. Their wardrobes would never be the same again.

To find out more on this subject Great War Fashion: Tales from the History Wardrobe by Lucy Adlington is available online and in bookstores. Pre-Order on Amazon US or Buy from Amazon UK.

Follow Lucy on twitter @historywardrobe or on the History Wardrobe facebook page. Visit www.historywardrobe.com for details of costume-in-context presentations, or www.greatwarfashion.com & www.ljadlington.com.

Good morning!

Can you tell me why ladies during the Edwardian era fold their hands on their lap with the palms facing upward? I’ve seen Cora do this on DA and have also seen photos of Queen Elizabeth The Queen Mother when she was Duchess of York, keeping her hands the same way. Is there any significance to it?

Thanks!

I suppose that since a lady was supposed to rest her hands quietly in her lap, holding them palms down wasn’t quiet! It is likely that it was also ill-bred to twitch or drum one’s fingers when bored, so palms up would keep one from doing so. 😉

You noted that the fashions of 1914 were quite alarming in their weights and constraints, and that correct dress still dictated respectability in pre-universal suffrage Britain. Agreed.

Now I wonder if countries that introduced universal suffrage decades earlier (especially New Zealand then Australia) reflected politically equality in their women’ dress. If this is correct, antipodean women should have well and truly freed themselves and their wardrobe from nasty restrictions.