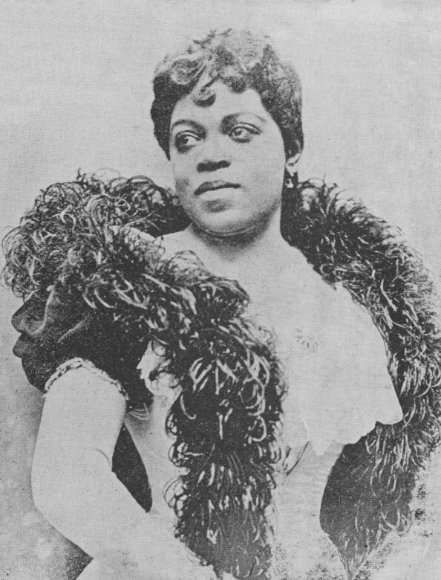

Opera singers were the world’s first pop stars, and the nineteenth century saw the apex of diva and divo worship, with hundreds of thousands left spellbound by the heavenly voices of Jenny Lind, Nelli Melba, Enrico Caruso, and Jean de Rezke, to name a few stars. Since this was before radio, and definitely before television and sound motion pictures, the opera found fans across the spectrum of class, social status, and even race. Into this unique setting, Matilda Sissieretta Joyner Jones made her debut.

Jones was born in Portsmouth, Virginia, in 1869 to Jeremiah Malachi Joyner, an AME minister, and Henrietta Beale, from whom Jones is said to have inherited her voice. When she was seven, the family moved to Providence, Rhode Island in search of better economic and social opportunities, and it was in her new home where Jones began the many steps which led to her lasting fame. She enrolled in the Providence Academy of Music in 1883, the same year in which she wed David Richard Jones, a hotel bellman who was to become her great sorrow until their divorce in 1900, and later at the New England Conservatory of Music. She made her formal debut in Boston before an audience of 5,000, and 1892 was the year in which she garnered the name “the Black Patti”:

If Mme Jones is not the equal of Adelina Patti, she at least can come nearer it than anything the American public has heard. Her notes are as clear as a mockingbird’s and her annunciation perfect.

Though she preferred to be called “Madame Jones,” the nickname stuck.

The 1890s were the pinnacle of Jones’s career. She performed throughout the United States, Europe, Australia, the Caribbean, South America, and South Africa; sang before four U.S. Presidents (Harrison, Cleveland, McKinley, and Roosevelt) and the British royal family; and became the first African-American to sing at the Music Hall in New York (renamed Carnegie Hall in 1893). She also collaborated with Czech composer Antonín Dvořák, singing parts of his Symphony No. 9, and a solo he wrote especially for her.

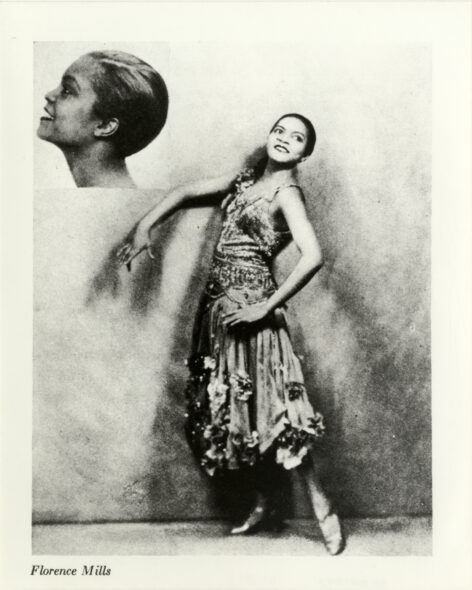

Despite this outstanding success, Jones found the doors to most of America’s concert halls closed to her, and when she formed the Black Patti Troubadours, the soprano diva discovered she had to walk the tightrope of American race relations as the group’s first shows featured only the minstrel and musical skits allowed to black performers. Jones was troubled by the minstrel skits, finding them demeaning, and she soon found a way to integrate opera arias and spirituals into the show to balance their image. Between the years 1896 to 1915, “Black Patti’s Troubadours” traveled internationally, performing operatic arias, art songs, and sentimental ballads, and served as training ground for thousands of black performers, including Bert Williams of Williams and Walker fame.

By the early 1900s, Black Patti’s Troubadours tightened its repertoire and now included original pieces which featured Jones in the diva roles denied to her: A Trip to Africa (1909-10), In the Jungles (1911-12), Captain Jaspar (1912-13), and Lucky Sam from Alabam’ (1914-15). During the travels of the group, later renamed the Black Patti Musical Comedy Company, accolades both written and tangible piled on her, and “Jones was given many gifts from admirers, among them, a medal from President Hippolyte of Haiti, a bar of diamonds and emeralds from the citizens of St. Thomas, an emerald shamrock from the Irish people of Providence and a diamond tiara from the governor general of a West Indies island. And she often wore her 17 medals across her chest during performances.”

Sissieretta gave two final performances: at the Grand Theater in Chicago and at the Lafayette Theater in New York City in October 1915, and returned home to Providence to care for her ailing mother. Her stint with the Black Patti Troubadours was rumored to bring in excess of $20,000 a year in profits, but Jones was penniless in her retirement, and she was forced to sell three of her four houses, and her jewels and mementos to remain solvent. When she died of cancer in 1933, at the age of 74, William Freeman, a real estate agent and president of the local NAACP had provided money for her bills and living expenses during the last years of her life, and he also paid for her burial in Grace Church Cemetery in Providence. A rather ignoble end for such a success, but Sissieretta Jones nonetheless paved the way for respected black entertainers to come, including Marian Anderson, who in 1955 was given the opportunity to sing in the Metropolitan Opera House of New York, which was denied to Jones in her lifetime.

Comments are closed.