For most girls of the Gilded Age, marrying a wealthy man was success enough, but for Mrs. Leslie Carter, this was the least of her accomplishments, which would eventually outstrip her coup of marrying up.

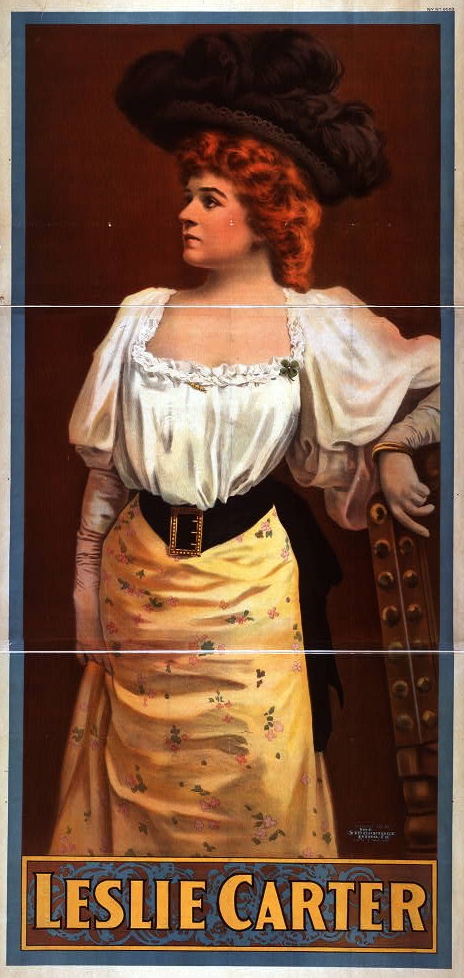

A native of Lexington, Kentucky, Caroline Louise Dudley was born in 1862 to Orson Dudley, a moderately wealthy wholesale dry goods merchant, and his wife Catherine. Most of her childhood was spent in Dayton, Ohio, where she nursed aspirations of becoming an actress–a very shocking desire in those days, since “actress” was practically synonymous with “prostitute.” As she matured, her vivaciousness and striking red-headed prettiness caught the eye of many, but she chose to wed Leslie Carter, a lawyer and son of a Chicago millionaire, in 1880. Their union produced a son, Dudley Carter, but trouble arose early on in the marriage. Leslie was attracted by her beauty and personality, and she by his good looks and wealth, but they were completely incompatible. This was further exacerbated by the newly-wed Mrs. Leslie Carter’s traumatized reaction to her wedding night and by her incredibly spendthrift ways.

Throughout their brief marriage, Caroline spent lavish sums and lavish amounts of time away from her husband, establishing herself in Europe’s capitals and classiest hotels, where she made it clear that she was not to be the respectable “little wife.” While she lived it up in Europe, Leslie Carter made plans to divorce his wife and hired his brother, also a lawyer, to monitor her activities. But Caroline stole a march on him, suing for divorce in 1887 on the grounds of physical assault and abandonment. Leslie Carter then counter-sued, charging that his wife committed adultery with no less than four different men.

A storm of the publicity Caroline dreaded fell upon her head, and the divorce proceedings created enough fodder to last for months on the front pages of Chicago’s newspapers. Her suit was proved flimsy and embarrassingly vague, particularly when Leslie Carter was able to produce the names, dates, and times of her adulterous liaisons. To her horror, innocent meetings Caroline made in New York with actor H. Kyrle Bellew for acting lessons were produced as proof of her adultery and Leslie Carter was granted his divorce. Humiliated and penniless, and also a single mother, the newly divorced Caroline Carter needed not only an escape, but a way to make a living, and she turned to the field that brought about her notoriety: the stage.

She made a bold move in approaching the famed producer and impresario David Belasco to train her in stage acting, but approach him she did, and despite her inexperience, Belasco saw something in her, his first impression of this fierce young woman as “a pale, slender, red-haired girl with a pair of green eyes, gleaming under black brows, who alternately wept and smiled, whose gestures were full of unconscious grace, and whose voice vibrated with musical sweetness.” In this step, Caroline hoped to avenge her wrongful divorce, stating:

I am going to be known to the world. Electric lights over the theatre lobbies will carry the name of Leslie Carter in five-foot letters. I hate the name, consequently I will bear it to the end. Newspapers shall spread it forth, the streets shall hum with it! Mrs. Leslie Carter! It shall be borne upon him by the printed and the spoken word! He cannot escape. It shall hound him until his last day.

Belasco quickly became Svengali to Mrs. Leslie Carter’s Trilby, and she was set to work in two minor vehicles in 1890, The Ugly Duckling, a fairy tales, and Miss Helyett, a comedy. Caroline’s skills weren’t polished enough for success, and Belasco resumed his tutoring while casting about for suitable plays to adapt for his eager protegee. In 1895, Belasco was able to secure funding for The Heart of Maryland, a Civil War play in which Caroline portrayed Maryland Calvert, a minor character, but one whose one major dramatic scene literally catapulted Mrs. Leslie Carter to fame.

In the play Maryland must save her lover Colonel Kendrick (played by Maurice Barrymore) from certain death as orders are given to ring the church bell, the signal that a prisoner has escaped. The sight of Mrs. Leslie Carter swinging in the belfry tower, her hands gripping the clapper to prevent the ringing of a huge curfew bell and her long red tresses streaming behind her, set New York audiences cheering, and her success was cemented. This play was followed by Zaza (1898) and Madame Du Barry (1901), both of which prompted the public to dub Mrs. Leslie Carter the “American Sarah Bernhardt.”

There was trouble in paradise, however, and the collaboration of Mrs. Leslie Carter and David Belasco grew shaky. Mrs. Leslie Carter agreed to one last play with Belasco, Adrea, which premiered in Washington D.C. in 1904. The mixed reviews and growing criticism of Mrs. Leslie Carter’s overemotional acting (some said hysterical) further contributed to the growing rift between the collaborators, but it was Caroline’s surprise remarriage which put an abrupt end to the Carter/Belasco partnership. Using her maiden name and giving her age as thirty, Mrs. Leslie Carter married actor William Payne in the home of an Episcopal clergyman in Portsmouth, New Hampshire in 1906. Unfortunately, this second chance at marital happiness marked the decline of her career, and though many claimed her success was solely due to Belasco’s genius, the irony was that the highly theatrical acting style in which Belasco trained her was outmoded by the mid-1900s, and audiences and critics were left cold by her melodramatic performances.

Further compounding the downward spiral of her career was the news that she was bankrupt in 1907. She continued to travel and put on plays in her usual lavish style, but the plays all lost tens of thousands of dollars, and every penny she did earn went directly to a receiver. After two auctions of her personal belongings and further theatrical flops, Mrs. Leslie Carter was dubbed “the queen of bankruptettes.” Now in her fifties, Mrs. Leslie Carter had to salvage her finances and her career and she entered the 1910s and 1920s drifting between cinematic versions of her best-known plays, shortened versions of Zaza, retirement, and rejection as being “too old.”

However, she bounced back a little in the late 1920s with roles in She Stoops to Conquer and a tour of The Shanghai Gesture. She relocated to Los Angeles in the 1930s, where she took small roles in two films, The Rocky Mountain Mystery and Becky Sharp, but it was evident that her ship had sailed. Nonetheless, even though David Belasco never spoke to or of her after her elopement in 1906, Mrs. Leslie Carter remained devoted to him, stating in her autobiography that “I had no more heart in the theatre. I bore a likeness to something that walked and talked and moved its body, but the soul had taken leave of absence…. I never felt myself complete without Mr. Belasco, without his sagacity, without his kindness, without his clear, sane dramatic feeling.”

After heartbreak, humiliation, and tribulations, the indomitable Mrs. Leslie Carter died in 1937, age 75. However, her mettle and grit proved everlasting, and her extraordinary life was fictionalized in the 1940 film The Lady With Red Hair, starring Miriam Hopkins as Mrs. Leslie Carter and Claude Rains as David Belasco. Read more about Mrs. Leslie Carter in Craig Clinton’s Mrs. Leslie Carter: a biography of the early twentieth century American stage star.

Thanks for this. I’ve never heard of her before and now I’m intrigued.

Thanks Elizabeth! I’ve discovered a lot of now-obscure people from the 19th and 20th centuries who were super famous in their day. I think it’s a shame that the influence of Broadway and just plain theatre-going has diminished to the point where great and famous actors and actresses (as well as playwrights) have been largely forgotten.