Contrary to public opinion, Madam C.J. Walker did not invent the hot comb or relaxers, and neither was she the only African-American beautician during the Gilded Age. What the former Sarah Breedlove was, however, was incredibly intelligent–a savvy entrepreneur, pioneering businesswoman, and shrewd marketer, she turned African-American beauty culture into a multimillion dollar empire never before seen. In the post-Reconstruction period, black women were alternately neglected by the vastly increasing companies catering to women’s haircare, cosmetics, and beauty, or sold toxic concoctions by greedy companies which promised “lighter skin” and “straight hair”, but ended up creating more problems for black women desperate to conform to the very narrow standards of beauty of the late 19th century.

Though working-class women, both black and white, lived in homes rarely fitted with modern plumbing or ventilation, and subscribed to old wives tales about hair-washing, this lack of care resulted in “rampant scalp disease: dandruff, lice, eczema, fungal infections, alopecia, and tetter, a particularly pesky form of psoriasis.” For black women, whose hair was characterized as “frizzy” or “kinky,” therefore “unattractive,” these diseases, which ultimately resulted in hair loss, were traumatic, and Sarah Breedlove was no stranger to this maddening cycle. Having been married and widowed by age twenty, and mother to a young daughter, A’Lelia, Sarah moved from Mississippi to St. Louis in the late 1880s, where her brothers made a living as barbers. There Sarah became a laundress, one of the few professions open to black women, where she worked six days a week washing, scrubbing, drying, pressing, and mending pounds and pounds of clothes for St. Louis’ elite.

“The work, all done by hand in wooden washtubs and iron pots of boiling water, was steamy, strenuous and laborious. Wet sheets and tableclothes doubled in weight. Lye soap irritated hands and arms. Heated flatirons were heavy, cumbersome and dangerous […] a broken dress button or a scorched shirttail meant a cut in pay, a reduction of a washerwoman’s weekly $4 to $12 wages.” (Bundles 46)

During this time, Sarah began to suffer from hair loss, presumably from the chemicals involved in washing, but most likely from the stress of being a single mother in a precarious financial situation. She turned to a variety of remedies, from home-made products to those purchased in stores, including the hair products manufactured by Annie Malone, an African-American beauty culturist and entrepreneur. Malone specialized in the different hair textures of black women’s hair, and worked to revolutionize hair care for African Americans, creating a variety of products, including the first patented hot comb. Malone’s line of hair care products, called Poro, a West African name meaning physical and spiritual growth, were sold by door-to-door saleswomen, and by the turn of the century, Sarah had become one of them.

After relocating to Denver, Colorado as a sales agent of Poro, Sarah–now married to newspaper sales agent, Charles Joseph Walker–struck out on her own as “Madam C.J. Walker,” creator of Madam Walker’s Wonderful Hair Grower. In later years, Sarah would use her story to inspire prospective black entrepreneurs, pointing to Divine intervention as the source of her scalp conditioning and healing formula, and imbuing it with a sense of mysticism by claiming the ingredients came directly from Africa.

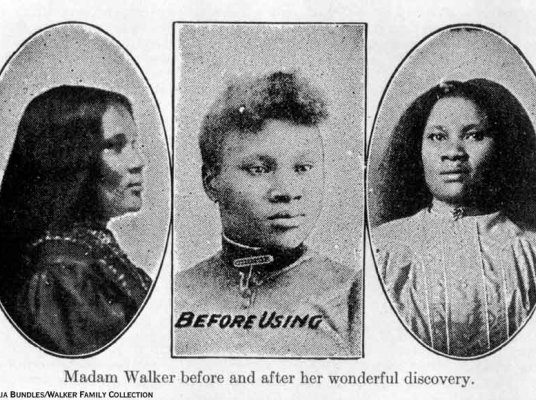

The truth was rather more mundane, and dangerously untruthful in the eyes of the furious Annie Malone, but Madam Walker possessed a flair for marketing and business on a much wider scope than Malone even dreamed. In the first eighteen months of business, Madam Walker embarked upon an intensive tour of the South, selling her products door to door, demonstrating techniques to promote healthy hair and diet, and coming up with new and innovative sales and marketing techniques. However, the best form of promotion was Madam Walker’s own hair, which, as seen in her advertisements, showed her hair before her hair treatments (short and damaged) and after (healthy, lustrous, long). By 1907, her first full year on the road, she earned over $3600, nearly tripling her 1906 earnings, which, compared to a black woman’s average wages of $96 to $240 a year, was an astonishing feat.

Madam Walker’s business expanded to such a degree, she moved her base to Pittsburgh, PA, where she opened Lelia College to train Walker “hair culturists.” While Madam Walker continued to travel across the United States, keeping her hand directly in the operations of the business by more demonstrations, personal sales, and training beauticians under her business model, her daughter A’Lelia was her second-in-command, hitting areas she didn’t have time to attend. In 1910, after scouting for a better location for her headquarters, Walker Manufacturing Co. moved in Indianapolis, Indiana, where she built a factory, hair and manicure salon and another training school. Now comfortably well-off, Madam Walker began to train and teach black women how to open their own businesses, lecture at conventions sponsored by powerful black institutions, and expand her influence as the image of what an African-American woman with a little ingenuity and talent could achieve (in a stroke of particular genius, Madam Walker expanded her business to black women in South America and the Caribbean, tapping into that definitely neglected market!).

So wealthy had Madam Walker become, white newspapers of the period could not ignore her, particularly when she moved to New York and startled residents of Upper Manhattan when she opened her first salon in an all white street. The crowning jewel in her empire was her mansion in Irvington-on-Hudson. Designed and built by Vertner Tandy, the first registered African-American architect, between 1916 and 1918, the $250,000 home (christened Villa Lewaro, from a suggestion by famous tenor Enrico Caruso) garnered much press in both the black and white news of the time, with The New York Times devoting a nice sized column detailing the architecture and amenities:

“A three-story and basement affair with roof of red tile, is in the Italian Renaissance style…it stands in the centre of a four-and-a-quarter acre plot…and has thirty-four rooms. In the basement are a gymnasium, baths and showers, kitchen and pantry, servants’ dining room, power room for an organ, and storage vaults for valuables. The visitor enters a marble room, whence a marble stairway leads to the floor above. On the first floor are the library and conservatory, a living room, a Louis XV drawing room…the second floor contains bedrooms, bathrooms, showers, dressing rooms, sewing rooms, and two sleeping porches. On the third floor are servants’ quarters. [Madame Walker] employs eight servants, including a butler, sub-butler, chef, and maids of all work. In addition to these she has a social secretary and a nurse. On the third floor are also bathrooms, a billiard room, and a children’s nursery.”

By Madam Walker’s death in 1919, aged 51, she had become the wealthiest African-American woman in America and the first self-made female American millionaire. She also became a legendary figure in the progress and achievement of African-Americans, particularly African-American women, in a time where their contributions to society were ignored or marginalized. For more information on Madam Walker’s incredible life, the biography written by Madam C.J. Walker’s great-great-granddaughter is an equally incredible resource!

Further Reading:

On Her Own Ground: The Life and Times of Madam C.J. Walker by A’Lelia Bundles

“Wealthiest Negro Woman’s Suburban Mansion: Estate at Irvington, Overlooking Hudson and Containing All the Attractions That a Big Fortune Commands.” New York Times Magazine. November 4, 1917.

Links:

Madam Walker Estate

Official Website of Madam C.J. Walker

Dear Ms. Holland,

What a fascinating blog, so chock full of information!

I just wanted to thank you for featuring Madam C. J. Walker and for citing my book, On Her Own Ground. As Walker’s great-great-granddaughter and biographer–and as president of the Walker Family Archives–I’m always thrilled when others are inspired by her story. Today our family keeps Madam Walker’s legacy alive through the Walker Theatre Center, a National Historic Landmark in Indianapolis (www.walkertheatre.com); through our books and speeches; through honoring successful entrepreneurs; and through our Walker Family Archive of photographs, letters, business documents and personal items that belonged to Madam Walker and her daughter, A’Lelia Walker.

[edit]

We hope you and your readers will visit our websites at

http://www.madamcjwalker.com

http://www.aleliabundles.com

http://www.walkertheatre.com

Here’s a link to our interview with U. S. Secretary of Labor Hilda Solis

http://tiny.cc/89jam

I just wanted to inform you and your readers of this very important fact – Madame C.J. Walker’s historic company still exists today and has never stopped manufacturing all of the original hair oils! The website also contains valuable information about Raymond Randolph’s purchase of the original Madame C.J. Walker Manufacturing Company in 1985 from the Walker Trustees in Indianapolis, Indiana and how his family continues to keep Madame Walker’s “true” legacy alive.

Angela Randolph

http://www.madamewalker.net

[comment edited to remain on topic]