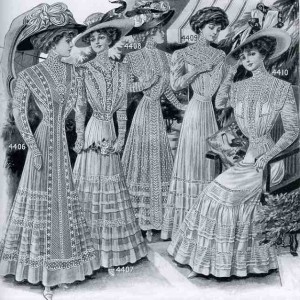

No matter the temperature, our sturdy Edwardians remained buttoned and corseted, which, since weather has largely remained the same in all corners of the globe, made for very uncomfortable times. Let’s explore how people at the turn-of-the-century kept cool amidst sweltering summer heat.

No matter the temperature, our sturdy Edwardians remained buttoned and corseted, which, since weather has largely remained the same in all corners of the globe, made for very uncomfortable times. Let’s explore how people at the turn-of-the-century kept cool amidst sweltering summer heat.

The Menorah: a Monthly Magazine for the Jewish Home, v29 (1900)

The problem of problems for the summer is. How to keep cool? Much depends on what we eat and drink, but more on what we wear. Strange there should be any doubt what the latter is, when the proofs of WHAT NOT TO WEAR are so much in evidence on a hot day. See that man in linen shirt and collar! Tiring of the effort to keep his neck dry by mopping, he inserts his handkerchief between skin and collar to save what is left of the stiffness in the latter. Compare with the man in shirt and collar of wool (negligee). The pitying smile on the face of the latter as he glances at the victim of linen tells the story in a nutshell.

Think this over a minute. If contact with linen causes so much distress to the neck, how are we to measure the mischief done where the entire body is covered with it?

Perspiration as it first leaves the pores is vapor, and as wool has a strong affinity for vapor it absorbs it as fast as it emerges from the pores. But wool has also a repulsion for water, so that the vapor taken up by it is not allowed to condense in the material but is passed through to the outside and evaporated.

What follows? That to keep cool in summer your underwear MUST BE WOOLEN. It is, of course, essential that the wool be of absolute purity. It is also necessary that the texture be of such weave and fineness as will give the maximum of lightness and porosity. These three requisites will be found combined to perfection in the aptly-styled “gauze weight” of the Dr. Jaeger System. In an undersuit of this extremely light all-wool Jaeger fabric you can defy Old Sol, and at the same time snap your fingers at sudden falls of temperature. Like a gull on the ocean, you can then enjoy life, whether borne on the top of a ‘-hot wave” or plunged without warning down the mercurial incline—secure in either case against prostration or chill.

May’s Anatomy, Physiology, and Hygiene (1899)

How to Keep Cool in Summer.—In summer we should eat less meat and less food than in winter. Usually our appetite is not so good in summer as it is in winter, and naturally, therefore, we take less food, and we should wear light clothing. Everything we do during the warm parts of the summer days we should do slowly and should not hurry. We should not walk much in the sun without being shaded.

How the Body is Kept Cool in Summer.—It would seem difficult to prevent the body from being overheated in summer when the air around us is so warm; and you might wonder, too, why it is that the blood of a locomotive engineer, or of a cook, who is in front of a hot fire all day long, is no warmer than that of persons who can keep cool. There are two ways in which the bodily heat is prevented from rising above 98 degrees when persons must be near furnaces and fires or are otherwise exposed to the heat.

Both methods depend upon the fact that whenever moisture or water leaves any surface it makes that surface cold; that is, it takes some of the heat of that surface with it. In India, the drinking-water is cooled by placing it in porous clay vessels which allow a little of the water to soak through, after which it passes off into the air and thus makes the rest of the water cool. If you wet your hand and then hold it in the air, it feels cold, because the water in passing into the air takes some of the heat of the hand with it.

In this way our blood does not get any warmer in summer than in winter. For in summer more moisture leaves the body than in winter. Moisture leaves the body in two ways: By the lungs and by the skin. We breathe more rapidly in summer than in winter, especially if it is very warm, and in this way, more moisture is given off to the air from the blood passing through the lungs. Then again, the expired air contains more moisture in summer.

Perspiration.—The moisture which passes off by the skin is called perspiration. This is taking place constantly through the pores, but in summer so much passes off that it collects in drops and is then called visible or sensible perspiration.

Ice-water in Summer.—There is no objection to ice-water in summer if you do not drink too much, and if you take but a little at a time. Some people get into the habit of drinking ice-water constantly. This is very unhealthy and will make them suffer. But if it be remembered to drink it slowly and only a little at a time, it will not usually do any harm.

Sunstroke.—When a person has been in the sun a long time, the heat of the blood may become so great, or the effect of this heat upon the nerves so serious, that it makes him dangerously sick; this is called sunstroke. It is a very dangerous condition. If you have to walk much in the sun, you should stop and go into the shade and rest as soon as you feel the least faint or dizzy.

From The Dominion:

How to Keep Cool on Hot Summer Days

THE use of a vacuum bottle as a Winter need, or as a requisite for the sick rooms, needs little argument in its favor, but it may not be generally recognized that the same bottle can be used as a means of keeping cool on hot Summer days. If a water bottle filled with hot water comes to the aid of the aged and cool-blooded individuals during the Winter, why not fill the same bottle with cold ice water in Summer and use it to cool overheated blood?

A national advertiser, in advertising his makes of water bottles, offers this suggestion:

“Here is a use for a water bottle many people don’t think of, because they usually think of it as a hot water bottle only. Fill it with cold water and use it to help keep cool.

“Hold it on the back of your neck when you are over-heated. Rest your neck upon it when the night is uncomfortably hot.

“Heat and discomfort quickly pass, as it cools both brain and body. Instead of a restless, wakeful night, you quickly sink into profound, refreshing sleep.

“Don’t forget your water bottle when you don’t need it to warm you. Use it as a cold water bottle and enjoy a new Summer luxury.”

From the New York Times:

Now that the torridity of midsummer is upon us, let me recommend to your readers a very simple, harmless, and effective device for getting and keep cool on warm nights. An ordinary rubber water bag half filled with cold water placed as a pillow under the head on retiring in about five minutes reduces the temperature of the whole body sufficiently to insure several hours of comparative relief and comfort.

During the sultry weeks in Paris dwellings of that city of light and brightness are kept cooler than those of America. Carpets are replaced by matting that can be sprinkled. Windows are closed at sunrise to keep in the cool night air until sundown. The courtyard is frequently watered to prevent its becoming heated and to keep up evaporation. Keep a large block of ice on a grooved marble table, the cool waste water draining through a concealed pipe in the standard of the table and connected with a refrigerator below, seeping over salad leaves and covered jars. By this device a uniform temperature is maintained.

The municipality aids the citizen by having the streets thoroughly watered and the trottoir (sidewalk) washed down long before Parisians are astir. Along the boulevards are large trees that turn the heat aside. There are little cafes with awnings drawn over the pavements, chairs around small tables, and for three half pence the thirsty man receives a glass of water from the garçon. French summer drinks are cooling rather than inebriating. Domestic wines, orgeat, raspberry vinegar, are dispensed in long glasses produced from the refrigerator.

Now that we’ve learned how to keep cool, let’s move on to the best part of summer: the food!

Pineapple Lemonade

Peel a ripe pineapple, grate the fruit, and turn over it the juice of five lemons. Then make a syrup of a pound of sugar and a pint of water by boiling them together for ten minutes. Cool the syrup and add it to the fruit, turn in a quart of cool water, and strain through a muslin cloth. Serve in a glass filled with crushed ice. If you want to make it quite pretty add a cherry to each glass.

Pour two gallons of cold water over a half dozen lemons thinly sliced and add to this not quite an ounce of ginger root. To this mixture add a pound and a half of sugar. Let it come to a boil; then add a tablespoon of cream of tartar. Strain and set in a cool place. When nearly cold add a yeast cake dissolved in a little lukewarm water; stir thoroughly; then set in a cool place overnight. In the morning mix well and bottle. Be sure to make the corking airtight and lay the bottles on their sides in a cool place. A small bottle of Jamaica ginger extract may be used in place of the whole ginger if more convenient.

From Treats from the Edwardian Country House:

Pimms

* 2 lemons, sliced

* 1 punnet of strawberries, quartered

* Peel of ½ cucumber

* Crushed mint

* 2 tablespoons of castor sugar

* Juice of 3 lemons

* 200ml Pimms

* 1 litre soda water

Put the sliced lemons, strawberries, cucumber peel, crushed mint, sugar, lemon juice and Pimms into a jug. Stir the ingredients until the sugar has dissolved. Add the ice and top up with soda water.

From Cassell’s Dictionary:

Lemonade.—This favourite beverage is easily made and extremely refreshing. To make a quart, take two lemons or more, according to taste, pare thinly off a little of the rind, or rub lumps of sugar upon it. Squeeze out the juice of the fruit, and mix it with two ounces of white sugar, including what has been rubbed upon the lemons. Add boiling hot water, and when cool enough strain the liquor. Dilute the preparation with water to the strength required. Should lemons not be in season, syrup of lemons may be used, or crystallised citric acid and sugar, adding a few drops of the essence of lemon. Lemonade, like all similar drinks, is rendered much more refreshing by being iced.

Lemonade (au lait).— Take half a pint of lemon juice, the same of white wine, three-quarters of a pound of loaf sugar, and a quart of boiling water. Mix, and when cold add a pint of boiling milk. Let it stand twelve hours, then pour through u jelly-bag. This makes two quarts: about seven lemons will produce half a pint of juice.

Lemonade (Soyer’s recipe).—Thinly peel the third part of a lemon, which put into a basin with two table-spoonfuls of sugar. Roll tho lemon with your hand upon the table to soften it; cut it in two lengthwise, squeeze the juice over tho peel, Sec, stir round for a minute with a spoon to form a sort of syrup, pour over a pint of water, mix well, and remove the pips; it will then be ready for use. If a very large lemon and full of juice and very fresh, you may make a pint and a half to a quart, adding sugar and peel in proportion to the increase of water. The juice only of the lemon and sugar will make lemonade, but it will then be deprived of the aroma which the rind contains, the said rind being generally thrown away.

Mint Julep.—Put about a dozen of tho young sprigs of mint into a tumbler. Add a tablespoonful of white sugar, half a wine-glassful of peach, and the same of common brandy, then fill up the tumbler with pounded ice.

Orangeade.—Squeeze out tho juice of an orange, pour boiling water on a little of the peel, and cover it close. Boil water and sugar to a thin syrup, and skim it. When all are cold, mix the juice, the infusion, and the syrup with as much more water as will make a rich drink. Strain through a jelly-bag, and ice.

Sherry Cobbler.—Take some very fine and clean ice, break it into small pieces, fill a tumbler to within an inch of tho top with it, put a table-spoonful of plain syrup, capillaire, or any other flavour—some prefer strawberry—add the quarter of the zest of a lemon and a few drops of the juice. Fill with sherry, stir it up, and let it stand for five or six minutes. Sip gently through a straw.

From Mrs. Rorer’s My Best 250 Recipes:

Creole Corn.—Peel and cut in quarters four good-sized tomatoes; put these in a saucepan with a dozen okra washed and cut in thin slices; cover and stew slowly for twenty minutes; add the pulp of a dozen ears of corn, a level teaspoonful of salt, one sweet pepper chopped fine, a dash of white pepper; cook over hot water for fifteen minutes; add either four tablespoonfuls of cream or two tablespoonfuls of butter, and send at once to the table.

This is one of the most delicious of all the summer vegetable dishes. Served with chicken it forms a good Brunswick stew, or it may be served as a vegetable with broiled or baked chicken. The accompanying starchy vegetable should be rice.

Peach Shortcake.—Sift two rounding teaspoonfuls of baking powder and one of salt with one quart of flour; add sufficient milk to make a soft dough; knead quickly, roll out in a sheet one inch thick, cut to fit the baking-pan, brush with milk, and bake in a quick oven for twenty minutes. Pull the sheet apart, butter the inside, and cover the under part with finely-chopped sugared peaches. Put on the upper crust, dust with powdered sugar, and send to the table with a pitcher of cream.

Lobster a la Newburg.—Boil a good-sized lobster; when cold remove the meat and cut in cubes of about one inch. Hard-boil three eggs. Put the yolks through a sieve ready for use; put into the chafing-dish one tablespoonful of butter and one of flour; mix; add two-thirds of a cupful of good milk or cream; add a little of this sauce, when it has thickened, to the yolks of the eggs; rub to a paste, mix them with the sauce; add half a teaspoonful of salt, a saltspoonful of white or black pepper and about half a saltspoonful of grated nutmeg or a drop of extract of nutmeg. This sauce should be thick and have the general appearance of mayonnaise dressing. Add the lobster. When hot it is ready to serve.

Wool underwear, eh? That sounds incredibly uncomfortable.

I thought the same thing. Woolen underwear? Talk about hot! (Not to mention itchy scratchy…)

I do like the cold water bottle idea. If I didn’t have central air conditioning (which, thank the Lord I do), I would use that method to cool myself down.

You should try some fine merino woolens, then. Wool can be soft, and lightweight, if it’s of a fine enough grade. The itchy wool sweater is itchy because it is of a coarser quality. Compare, for example, the difference between a pashmina or cashmere sweater, and a rough ski sweater – all of them are wool. Unlike other fibers, lightweight wool does breathe, and is a lot less stinky than cotton.

The itchiness is because the yarn comes from some sheep breeds whose wool is more suited for rugs or outer-wear (like coats) instead of being next to the skin. (And, some people may be allergic to lanolin or chemicals that have been used to process commercial yarn).

Merino wool is definitely next-to skin. Correction – pashmina and cashmere don’t come sheep; these come from goats.

If you want to learn more, get “The Fleece & Fiber Sourcebook: More than 200 Fibers, from Animals to Spun Yarn” by Deborah Robson and Carol Ekarius. This is an excellent resource, and the authors talk about how different breeds originated (many were begun or “improved” in the 19th century in England) and wool from different breeds can be used. Your local library may have a copy.

Thanks for adding your expertise to the conversation, Lola! I’m no textiles expert, but I figured those Jaeger wool union suits and combinations had to work, since they were so popular during the Victorian and Edwardian eras.

By the way, she talks about the itchiness factor in the book.

Woolen underwear? Not only will you sweat like crazy, but most likely develop a rash O.o

Haha! A textile historian shows an extant Jaeger wool petticoat from the 1880s here. The wool was superfine, very soft wool–usually merino. Plus, wool doesn’t stink when you sweat!