Don’t Waste Bread! © IWM (Art.IWM PST 13354)

It must have been a great shock to the Edwardians to go from extreme lavishness in meals to extreme want during the height of the war. During the early months, food prices soared as Britons fearfully stocked up on basic necessities and other foodstuffs. However, this was quickly curbed by the newly-founded Cabinet Committee on Food Supplies, who on August 7th, fixed the maximum prices for food “such as 4½d. per lb for granulated sugar, 5d. for lump, 1s. 6d. per lb for butter, 8d. for margarine, 9½d. for Colonial cheese, and 1s. 4d. and 1s. 6d. for continental and British bacon.” Many considered these prices extravagant, what with the menus in Maud Pember Reeves’ 1913 study on poverty, Round About on a Pound a Week, averaging about 10s. for 2 oz of tea, ½lb of sugar, 4 oz of butter, and a loaf of bread per day. Ironically, just as prices were fixed and rationing set in, luxury foods fell drastically in price due to the lack of entertaining (for example, pineapples fetched only 1s.!), and the wine trade just about collapsed.

During the autumn and winter of 1914, supplies of fuel and light were curtailed, street lamps were dimmed, and no long lines of lights were permitted. In London, Mrs. C. S. Peel declared that the city had gone back twenty years as regards to lighting and “by the end of the war it was almost as dark as the Middle Ages.” New laws required that everyone put up blinds to the windows and keep them drawn at night at the risk of a fine of up to £100 or six months’ imprisonment–a precaution that became imperative once Zeppelins began dropping bombs on England at various intervals throughout the war. By early 1915, the coal shortage had shortened people’s tempers, and the suspicion of neighbors hoarding private stashes of coal or even of coal mine owners profiteering were frequent complaints. The price of coal rose steadily each month, and the coal queue became as familiar a site as the food queue. To mitigate the acute fuel shortage, newspapers filled their pages with advice on fuel-saving cookery and fuel substitutions.

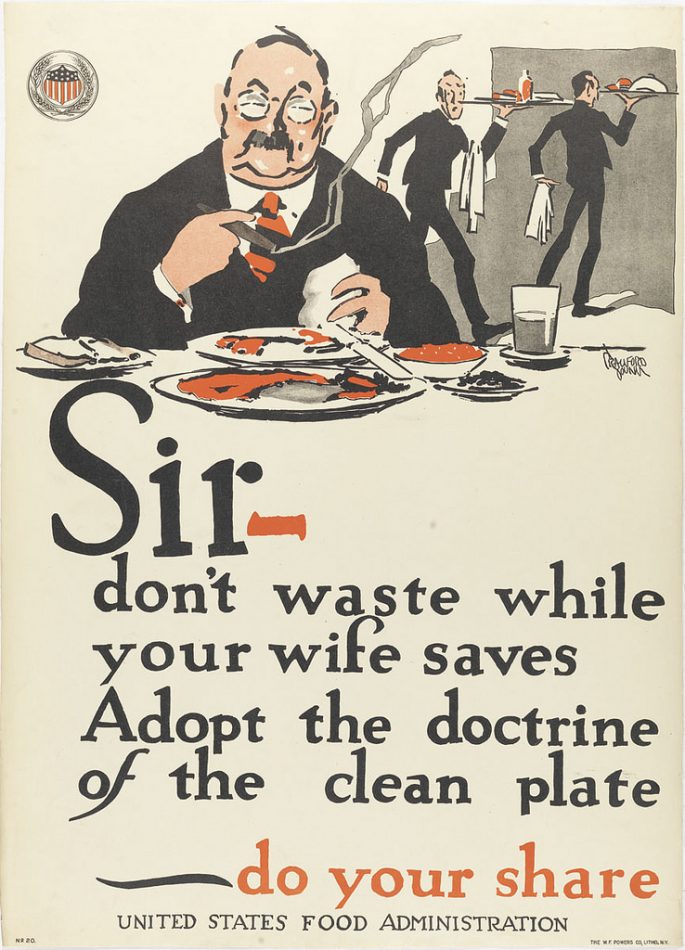

In December 1916, after a bleak autumn (due to the shortages and the news of the Somme), a Food Controller was appointed and a Ministry of Food established “to promote economy and to maintain the food supply of the country”. Yet, it was not until 1917, when the Germans began their unrestricted U-boat warfare, that the British government realized how vulnerable the country was to being cut off from their imported food supplies. In April of that year, 555,000 tons of shipping alone were lost in the submarine campaign . In response, the Food Controller authorized the organization of a national kitchen, where ostensibly healthy and nourishing food was cooked and served to the masses now that most men had been called up to the Front and women had taken their places in the workforce. The Board of Agriculture also sent instructors around the country to demonstrate bottling and canning fruits and vegetables to cut back on waste, and the London County Council issued posters advising people to buy bread by weight (as the poor did) rather than by the loaf.

Months later, when the food shortage became more serious, control, or rations, grew stricter: “to throw rice at weddings became a criminal offense, the sale of luxury chocolates and sweets were stopped, the use of starch for laundering was restricted, horses and cows and even the London pigeons were rationed, no corn was allowed for cobs, hunters, carriages horses and hacks, the amount of bread or cake sold at tea shops was reduced to 2 ounces, and it became an offense to adopt and feed stray dogs.” Butchers were ordered to display price lists, and bakers, with only barley, rice, maize, beans, oatmeal and potato permitted, were forbidden to bake anything but Government regulation bread. Everyone was advised to “Eat slowly: you will need less food.” or “Keep warm: you will need less food.”, yet no explanations were given on how to keep warm with fuel rationed and an insufficiently fat diet.

The winter of 1917 saw the formation of food queues, where people in the poorer districts waited outside of shabby shops for hours, and the better-off sent their servants round to fetch what they could. This latter practice and the resentment it stirred up no doubt convinced the Government to institute compulsory rationing in 1918. After February 1918, it became impossible in London and the six home counties to buy butter, margarine, or meat without cards; by the end of April, everyone was required to register for bacon as well. Those in the country, and the aforementioned well-to-do, were a tad better off, since they had gardens and livestock, but food shortages, inflation, and rationing remained a threat to the average Briton’s meals even after the U-boat campaign ended in August 1918. Yet, rationing did have a bright side: the malnutrition documented in the poor during the Edwardian eras had all but disappeared, and no one truly starved.

Sources:

How We Lived Then, 1914-1918: A Sketch of Social and Domestic Life in England During the War by Mrs. C. S. Peel

Camille DeAngelis tries two recipes from the Peel book, Savoury War-Time Pie & War-Time Soup

Rationing and Food Shortages during the First World War – Imperial War Museum

Rationing – WWI Propaganda Posters

Rationing and World War One – History Learning Site

Food rationing in Britain in the First World War – Join Me in the 1900s

From Beef and Chocolate to Daily Ration–British Rations in Transition, 1870-1918

The Home Front in World War One: Rationing of Basic Foodstuffs – BBC History

Great post! I guess people were supposed to jump up and down to stay warm! It’s amazing what people had to go through.

I know right? I can only assume that the Government’s first priority was to make sure there was enough relatively affordable coal and fuel to go around, so the opposing forces of no heat and no fatty diet didn’t cross their mind..

Loved this post.

The story of rationing is an important one since it shows how an entire nation can collectively respond to extreme circumstances (despite the odd hoarding). But two questions remain. Why did it take till 1918 to institute rationing? And what was the “national kitchen, where ostensibly healthy and nourishing food was cooked and served to the masses” – a soup kitchen in each city?

The Government tried to institute voluntary rationing in 1917, probably hoping everyone’s good nature/patriotism would urge them to cut back on their food purchasing. Of course it failed, which is why first London and the home counties instituted compulsory rationing, and then it was extended to the rest of the country. Regarding the national kitchen, it was a semi-soup kitchen, where food was cooked and fed to people with tickets, but fuel-saving and ration cookery classes. It actually did not take off as well as the Government had hoped, but a few cities set up their own versions.

Well, that’s something! I wonder if we’ll see any evidence of rationing at Downton?

The end of S2 touches on it a bit.