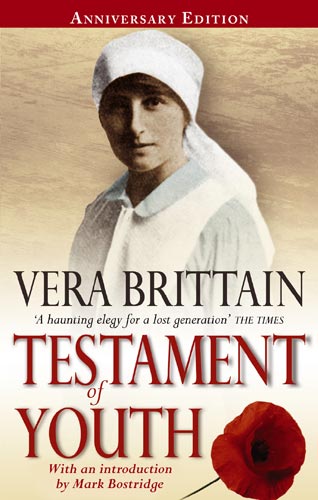

Thanks to Vera Brittain and her memoir, Testament of Youth, the most enduring female image of WWI is the VAD. At the outbreak of war, there were already thousands of members of the voluntary organization, which had been founded in 1909 under the joint efforts of the British Red Cross Society and the St. John Ambulance Society. Numbers swelled when many realized the seriousness of the war, and these untrained nurses–to the consternation of trained professional nurses–soon filled positions in hospitals both military and auxiliary. The relationship between professional nurses, who put in years of schooling and training before being considered fit for work, and VADs could be strained, particularly when many VADs were upper class and aristocratic girls who had never worked a day in their lives. Nevertheless, but the end of the war, professional nurses and VADs proved their collective mettle in the cooking, nursing, cleaning and administration of hospitals.

Voluntary Aid Detachments were organized in each county and consisted of men (yes, men!!) and women:

The Men’s Detachment

1 Commandant

1 Medical Officer

1 Quartermaster

1 Pharmacist

4 Section Leaders

48 Men

The Women’s Detachment

1 Commandant (man or woman)

1 Medical Officer (if the commandant is not a doctor)

1 Lady Superintendent (who should be a trained nurse)

1 Quartermaster (man or woman)

1 Pharmacist

20 women, of whom four should be qualified as cooks

Each Red Cross detachment was registered by the Council of the British Red Cross Society, given a number by the War Office, formed part of the Technical Reserve, and was inspected annually by an Inspecting Officer detailed by the General Officers’ Commanding.

To focus on the women’s detachments: those who joined the VAD were trained in cookery, sanitation, bandaging and dressings, washing of bodies and linens, and proper procedure before, during, and after surgeries. To become a VAD Member, a woman would write to her Country Director for instructions, or to the Secretary of the Joint Women’s VAD Department, which was stationed inside Devonshire House, who would then forward the name of her local County Director.

For admittance to nurse in a military hospital, prospective VADs were required to be aged 21-48 for home service, or 23-42 for foreign service. On completion of a probationary period of one month, they then signed a contract for six months service, and were paid £20 per annum for the first six months. £22 10s per annum was paid for the signing on of another six months, and there were further increments of £2 10s each half year until the salary reached £30 per annum. They were given an allowance of £5 per annum for uniform (either the black and white or grey uniform of the St. John or the blue uniform of the BRCS, and a small handkerchief cap). Lodging, food, washing, and traveling expenses were paid. For work in an auxiliary hospital, the VAD signed a contract before admittance, stating she would remain for three months after a fortnight’s probation. The VAD working in an auxiliary hospital–frequently converted schools, country houses, and large village buildings–had to provide her own uniform (Garroud’s was a popular destination, though some ordered a custom uniform from smart department stores like Harrods), but her other expenses were paid.

Gilbert Stone detailed the daily duties of a V.A.D. in Women War Workers:

Those who work in a V.A.D. hospital have, on the whole, an easier time than those in a military hospital. The hours are shorter, and allowance is made for human weakness by more regular time off every day and precious half-days off every week. On the other hand, the military hospitals offer you gold for your services not very much gold, but enough to live on. Thus you cease to be a voluntary nurse in the accepted sense, but you are still under the wing of either the Red Cross or the St John’s Ambulance.

The day work begins at 7 a.m., when the kitchen staff and the housemaids arrive, and the hospital is swept and polished, the beds are made, and the men’s breakfast is served. The men who are well enough to get up are expected to help make beds and sweep the wards. After breakfast the night nurses go off and the day nurses arrive. This is the

most instructive time for the V.A.D. nurse, for now the dressings are done by the sister in each ward. In most of the military hospitals the professional probationers help her, and the V.A.D. only picks up unconsidered trifles of knowledge, but in the V.A.D. hospitals she is at the right hand of the sister, and if she has the good fortune to work under one who knows how to give the amateur credit for slight signs of human intelligence she soon becomes a very useful member of the nursing staff.

The doctor’s round is the chief event of the morning, and after that the men who are well enough go out for a walk or drive or pass the time with needlework and games in the recreation room. The afternoon is spent by the men in sleeping, walking, or entertaining visitors, and by the V.A.D.s in light ward work, such as washing and ironing ties and bandages, tidying the lockers and medicine cupboards, and cutting up dressings. The afternoon is the time when the wards are expected to be in perfect order beds not an inch out of line, castors all turned the same way, nothing unnecessary on the lockers, and no speck of dust anywhere.

The evening again bristles with work and interest. Dressings and fomentations to put on, beds to be made, medicines to be given, and hot-water bottles to be filled. At 9 o’clock the lights are turned out, the night sister and her

nurses come in and take possession, and the day staff is dismissed.

Thekla Bowser, author of The Story of British V.A.D. Work in the Great War, describes work for V.A.D.s in France:

There are hundreds of V.A.D. members working as nurses and orderlies in the great Military Hospitals at the various Bases; there are dozens of members working in the same way in Auxiliary Red Cross Hospitals; there are members who spend their whole lives on railway stations, attending to the wounded as they come straight down from the firing line. There are Units of girl motorists who drive ambulances, and dozens of others who run canteens for convalescent soldiers who have not had the luck to be sent to England and who are sadly in need of the understanding word given by a woman whilst she ministers to their physical comforts. Some V.A.D. members do nothing but clerical work, many being engaged in the sad labour of trying to trace “Missing” men.

There are in France a great many large Hospitals which come under the general term of Red Cross Hospitals. This means that they are not General or Stationary Military Hospitals, but are kept up by Red Cross funds and are staffed by Red Cross members, though in every case fully trained Sisters are in charge of the wards. In these Red Cross Hospitals the work for V.A.D. members is apportioned with the greatest care. There are those who have had some nursing experience who are put into the wards to act as probationers under the Sisters. When there is a big push on, and the Hospital is filled to overflowing by wounded men who come down direct from the Front, these girls have the chance of proving themselves exceedingly useful to the Sisters.

By the end of the war, thousands of British women served on various Fronts (and some had died from shelling or illness), thus proving their worth to men and to society–and also to professional nurses. 😉

For a little more information, the British Red Cross Society has uploaded some letters of a VAD, and an excerpt from a cookery handbook for VAD cooks! Sue Light’s Scarletfinders website and its accompanying blog, This Intrepid Band, are also excellent resources for women’s nursing in WWI.

Further Reading

Your Daughter Fanny: The War Letters of Frances Cluett, VAD by Bill Rompkey and Bert Riggs

Testament of Youth by Vera Brittain

A Volunteer Nurse on the Western Front: Memoirs from a WWI Camp Hospital by Olive Dent

Dorothea’s War: The Diaries of a First World War Nurse by Dorothea Crewdson and Richard Crewdson

Oh yes agreed. This is the most important aspect of Doing One’s Bit: “There are in France a great many large Hospitals which come under the general term of Red Cross Hospitals. This means that they are not General or Stationary Military Hospitals, but are kept up by Red Cross funds and are staffed by Red Cross members”.

The Voluntary Aid Detachments were not middle class twits who simply worried about their nail polish chipping (as some snooty men implied). Those who drove ambulances, made beds, ran canteens, gave out medicines, filled hot-water bottles and kept the ward floors clean…. they were truly heroes during the miserable 4.5 years of the War to End All Wars.

Agreed! But we still cannot forget the professional nurses of the Territorial Force, Queen Alexandra’s, Navy, etc who worked tirelessly without any of the publicity or glamour allotted to the VADs.