With 2017 lurking just around the corner, there has been a slight uptick in books published about the United States’s involvement in the First World War. Which is kind of funny–for me at least–because WWI is one of the forgotten wars in American public memory (the others are the Spanish-American War and the Philippines War). You can say Lexington and Concord, Gettysburg, Normandy, Seoul, Saigon…and images and associations immediately flood your brain. Meuse-Argonne, Cantigny, and Belleau Wood mean nothing, except perhaps assuming they are places in France.

As a result, I was surprised, and yet not surprised, while reading First Over There: The Attack on Cantigny, America’s First Battle of World War I by Matthew J. Davenport, to discover a major commemorative event celebrated in the United States that is now a footnote in history. Davenport even says that “[t]hrough the 1920s and ’30s, ‘Cantigny’ remained a symbol of American sacrifice and triumph, a uniting emblem that finally exorcised the dividing demons of the Civil War in a way the Spanish-American War never could. But then came Pearl Harbor. And D-Day. And the Bulge. And in the wake of these epochal events, the 1st Division’s attack at Cantigny lapsed into footnotes, its story left to slumber for a century.” 1

Though the United States declared war on Germany in April 1917, the American Expeditionary Force didn’t see real action until late spring of 1918: May 1918, to be more exact, and the Battle of Cantigny to be more precise. Arthur Wilson Page describes the significance of the battle:

The trial was at Cantigny. It was, naturally, planned some time in advance, but in the march of events a thing happened the day before the Cantigny attack which more than ever made the demonstration of American fighting ability necessary. Our attack was to begin on the morning of May 28th. On the morning of May 27th, a great mass of German troops suddenly pushed across the Ailette, up over the strong position of the Chemin des Dames, and before the day was over the French lines were completely broken, and the Germans had crossed the Vesle on their way south to the Marne. The communiques that reached Paris on the night of the 28th told of the rapid and continuous German progress. But there came also that night another piece of news. The American Army had at last actively entered the war. The 1st Division shed a bright little ray of light on the otherwise dismal picture. And this ray of light was of great significance, for if the Americans could successfully meet the Germans, the Allies were assured an effective force big enough to win the war—the Americans were then arriving at the rate of 250,000 a month. If the Americans could not successfully meet the Germans, then, well, the situation was very bad indeed.2

The 1st Division of the AEF captured Cantigny and ably defended itself against German counterattacks, thus proving that the Americans could hold their own weight.

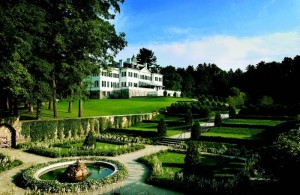

News of the AEF’s first successful action in the Great War filled the newspapers back home, and after the war, as Davenport stated, “Cantigny Day” was celebrated alongside Memorial Day during the 1920s and 1930s. So as you’re commemorating the veterans of America’s wars on Monday, don’t forget to think about the 1st Division on May 28th! If you’re in the Chicago area, stop by the First Division Museum at Cantigny Park, which was founded to commemorate the division by Colonel Robert R. McCormick, publisher of the Chicago Tribune, who fought with the division in the First World War.

Comments are closed.