Published anonymously (Google Books attributes the text to M. E. Clark), the author tells of her time as a nurse in the British Field Hospital for Belgium organized by a British woman and under the patronage of Elizabeth, Queen of the Belgians between August 1914 and October 1915. Antwerp fell to the German Army after an eleven day siege in October 1914, forcing the Allied nurses, soldiers, civilians, and members of the Belgian Royal Family to retreat. The author and her fellow nurses remained in Antwerp through the siege until the press of the German army compelled them to pack their equipment and escort their patients to Ghent. The following is an excerpt of the harrowing flight.

We felt in taking these buses that we were no longer robbing the Marines. Many of them were with us; many more were dead and had no use for them. It was now 3 p. M. on Thursday. As soon as the five buses arrived we commenced loading them up with our wounded. Those who could sit up were placed on top and the stretcher cases lay across from seat to seat inside. We formed a long procession, for there were five private cars as well. My car was the first to get loaded, and I was put in charge of the inside passengers. Shall we ever forget the loading up of those cars? They tried to save all the theatre instruments. What an eternity it seemed! Just sitting still, with the guns at last trained on to our locality.

One of the young doctors ran upstairs for his kitbag; half-way up, the wall suddenly collapsed, revealing the next house in ruins. He left that kitbag behind! Even to the last minute patients arrived, chiefly British. Just before we started a tall Marine in a navy jersey and sailor’s cap was helped in. He sat in the corner next to me. All his ribs were broken down one side, and he had no plaster or support. Opposite me were two Tommies with compound fractures of the leg. I placed both legs on my knees to lessen the jolting.

The Marine suffered in silent agony, his lips pressed tightly together, and his white face set. I looked at him helplessly, and he said “Never mind me, Sister; if I swear don’t take any notice.” Fortunately, they had pushed in two bottles of whiskey and some soda-syphons; I just dosed them all around until it was finished. Placing the Marine’s arm around my shoulders, I used my right arm as a splint to support his ribs, and so we sat for seven and a half hours without moving. Then another nurse took my place and I went up on top. During the first part of the ride I bethought me of that tube of morphia, and it came in very useful, as I gave each of those poor sufferers one or two tablets to swallow.

How can I ever describe that journey to Ghent of fourteen and a half hours? No one but those who went through it can realize it. Have you ever ridden in a London motor bus? If not, I can give little idea of what our poor men suffered. To begin with, even traversing the smooth London streets these vehicles jolt you to bits, whilst inside the smell of burnt gasoline is often stifling, so just imagine these unwieldy things bumping along over cobble stones and the loose sandy ruts of rough tracks among the sand-dunes, which constantly necessitated every one who could, dismounting and pushing behind and pulling by ropes in front, to get the vehicle into an upright position again, out of the ruts. When you have the picture of this before you, just think of the passengers—not healthy people on a penny bus ride, but wounded soldiers and sailors. Upon the brow of many Death had set his seal. All those inside passengers were either wounded in the abdomen, shot through the lungs, or pierced through the skull, often with their brains running out through the wound, whilst we had more than one case of men with broken backs. Many of these had just been operated upon.

We started from the Boulevard Leopold at 3 in the afternoon. We arrived in Ghent at 5.30 next morning. For twenty-four hours those men had had no nourishment, and we were so placed that it was impossible to reach them. Now that you understand the circumstances, I will ask you to accompany me on that journey.

Leaving our own shell-swept street which seemed like hell let loose, we turned down a long boulevard. From one end to the other the houses were a sheet of flames. We literally travelled through a valley with walls of fire. Keeping well in the middle of the street we constantly had to make detours to avoid large shell-holes. At last we arrived at one of the large squares near the Cathedral. That appeared to be intact, whilst the Belgians had taken Rubens’ and Van Dyck’s famous pictures and hidden them in the crypts.

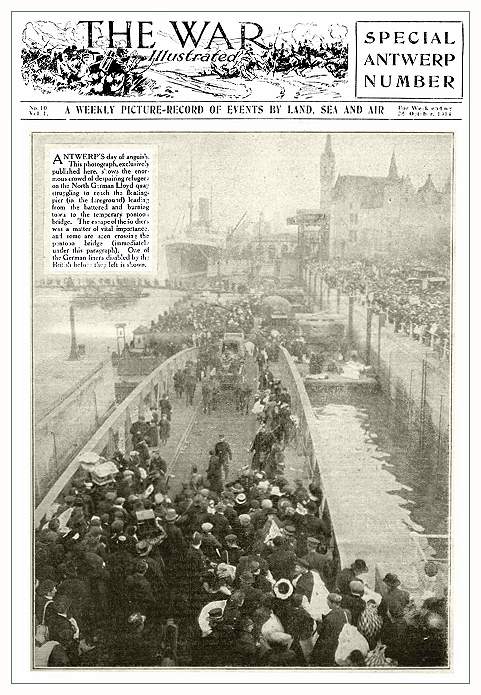

Every sort of vehicle in existence filled that square. It would have been possible to have walked across on the top of the cars. The only way to get out of Antwerp was across the Scheldt by a pontoon-bridge made of barges with planks between. It would not bear too much traffic, so the authorities let the people and vehicles cross one by one, still looking at passports.

For one and a half hours we stood there waiting for our turn to come. Just after we were safely over a shell struck the bridge and broke it in half.

From Antwerp to St. Nicolas is about twenty miles. It was the Highway of Sorrow. Some people escaped in carriages and carts, but by far the greater number plodded on foot. It was now 5 P. M. on an October evening; there was a fine drizzling rain; it was cold and soon it was dark. Along that road streamed thousands, panic-stricken, cold, hungry, weary, homeless. Where were they going? Where would they spend the night? Here was a mother carrying her baby, around her skirts clung four of five children, small sisters of five or six carried baby-brothers of two years old. There was a donkey cart piled high with mattresses and bundles and swarming on it were bedridden old men and women and babies. Here was a little girl wheeling an old fashioned cot-perambulator, with an old grey-bearded man in it, his legs dangling over the edge. Suddenly a girl’s voice called out of the darkness, “Oh Mees, Mees, take me and my leetle dog with you. I have lost my father and he has our money.” So we gave her a seat on the spiral stairs outside.

Very soon all the ills that could happen to sick men came upon us. The jolting and agony made them violently sick. Seizing any utensil which had been saved from the theatre I gave it to them, and we kept that mademoiselle busy outside. All along the road we saw little groups, weary mothers sitting on the muddy banks of a ditch sharing the last loaf among the family. After some time of slow travelling we came to St. Nicolas. Here the peasants ran out warning us, “The Germans have taken the main road to Ghent and blown up the bridge.” So we went on by little lanes and by-ways across the sand dunes and flat country that lie between Belgium and Holland.

We were very fortunate in having with us a Captain of the Belgian Boy Scouts. He knew the way and guided us. Soon the order went forth from car to car, “Lights out and silence!” Later on we saw the reason for this; across some sloping fields by a river we saw the tents and glimmering lights of the Germans. We passed very few houses, as we avoided towns and villages; any habitations we saw were shuttered and barred, for the people hid in terror expecting every one who passed to be the dreaded enemy. All this time our men were in torture, constantly they asked “Are we nearly there, Sister? How much longer?” I, who was strong, felt dead beat, so what must they have felt? One weary soul gave up the battle and just died. We could not even reach him to cover his face as he lay there among his companions.

From St. Nicolas I was faced with new anxiety. Where were our friends who went to Ghent with the first convoy of wounded? Had they taken the main road and fallen into the hands of the Germans? I thought of all the tales I had heard of the treatment Englishwomen received at their hands. At any place where people were visible we anxiously inquired if three buses had passed that way earlier. We could get no satisfactory answer.

Soon we began to meet the first detachments of the Expeditionary Force. In a narrow lane with a ditch on one side lay an overturned cannon whilst a plump English Major cursed and swore in the darkness. Then a heavy motor lorry confronted us; one of us had to back till a suitable place came in the narrow lane where we could pass. Later on we met small companies of weary Tommies, wet and footsore, who had lost their way. Our Scout Captain warned them to turn back, telling them the Germans had by now entered Antwerp, but they did not believe us. Even had they believed us, they had their orders to relieve Antwerp, so to Antwerp they went, never to return.

At last that weary night came to an end. For some hours I had been relieved by another nurse, and sat on top in the rain and cold. The medical students were so worn out that they lay down in the narrow passage between the seats and slept, oblivious of our trampling over them. Before dawn we entered the suburbs of Ghent.

— A War Nurse’s Diary: Sketches from a Belgian field hospital by M. E. Clark (1918)

I’ve read much of what is available online of M.E. Clark’s diaries – stunning stuff with so much incredible detail of the conditions under which citizens, soldiers and other war personnel lived. Other inspiring stories: Edith Wharton’s Fighting France, Mary Smith Churchill’s You Who Can Help, Ruth Gaines’ A Village in Picardy, and Mildred Aldrich and her diaries about WWI. Thanks for this gritty post.

Yes, Clark’s book is incredibly detailed. It’s the backbone of a future WIP. ^^

And thanks for the other recs. I’ve been wading through Google Books and Open Library for a while to find more wartime reminisces written by women.