THE editors got back from their Irish trip in time to see how London received the news of the armistice. They had had a rough encounter with the Irish sea–two encounters, indeed, one going and one coming back. It lived up to its tradition as an unruly, restless and troublesome teapot ocean.

Three times, in all, the editors have compassed its waters, and in each instance they found the Irish sea in an ugly mood. The packet on which they went from Holyhead to Dublin had its nose under the billows half the time, and the same little vessel on its return performed amazing stunts in riding alternately on one ear and then on the other, rolling and wallowing in the angry waves in ways quite disconcerting. It was a positive relief to put one’s feet again on dry land, in the comparative security, if not quiet, of a London crowd celebrating victory after four long years, and more, of war.

The news of the signing of the armistice was given out by Premier Lloyd George to the papers a little before 11 o’clock on Monday, November 11. Up to that time London had preserved its usual phlegmatic calm. The successive announcements, in the closing days of the war, that Turkey had succumbed, that Austria had sent up the white flag, that the Kaiser had abdicated, and finally that Germany had sent its representatives to General Foch to arrange for a suspension of hostilities — all failed to disturb the Londoner in the pursuit of his established and historic routine. Apparently everything was coming out as England expected, and there was nothing to do but await events. The crash of empires and the fall of dynasties were the mere incidents of an arranged schedule.

The armistice was signed at 5 o’clock in the morning. The news accounts here have it that New York and Washington got word of the great consummation at 3 o’clock A. M., and promptly proceeded to celebrate; and doubtless the Pacific Coast was favored with the same happy information sometime about midnight, or shortly thereafter. Making due allowance for all differences in time, London and England should have been notified of the result early in the day, immediately after the signing of the document. But the London evening papers are poor contraptions, and they have a way here of awaiting official announcements. It isn’t news until the King, or the Premier, or some other great man has said it or done it. Or perhaps the censor was still on the job. In any event, the method of communicating to the public the great fact that Germany had officially acknowledged that it had lost was through Lloyd George.

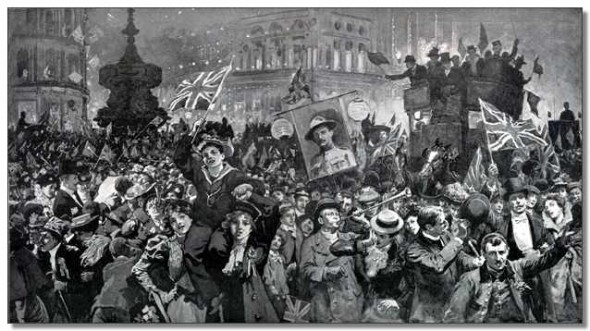

The day was threatening and misty; a very poor time for a public celebration of any kind. Then a lorry came lumbering up the Strand firing anti-aircraft guns. The significance of the exploit was not at first clearly understood. Some thought it was a final German air raid. But at last it dawned on the London mind that the war was over; and the impossible happened. London cast all reserve to the winds and let itself loose in a spontaneous and mighty demonstration. It was mainly a thing of moving and joyous crowds, going somewhere, anywhere, and making a noise—not a din after the American fashion, but yet a fairly noisy noise, all quite seemly, disciplined and respectable.

London is not yet thoroughly up in the art of getting the most out of a tin horn or a cow-bell. But the crowds, the crowds were enormous, and they were everywhere. It is said that London has 7,000,000 people. It must be an underestimate. Far more than that number apparently assembled at Trafalgar Square and before Buckingham Palace, and marched in platoons or companies or irregular regimental formations up and down the Strand. Or perhaps it was the same millions going in turn to all these common meeting places.

The crowd before the palace wanted to see and hear the King and Queen. That royal lady has a very large place in the calculations of the English people. “We want King George!” cried the people. The thoughts of more than one American went back to memorable and unexampled scenes in Chicago in 1912, when uproarious throngs insistently proclaimed “We want Roosevelt!”

There the very air was tense with the electric fervor of irrepressible feeling loudly and vehemently expressed. Here, where they have King George, and evidently intend to keep him, there was no emotional outburst, no passionate outcry, no mob frenzy, merely the more or less formal call of a disciplined people to see their King, doubtless because they reasoned among themselves, in good English style, that it was the correct procedure in the circumstances. There is no denying the popularity of the King, however. If they were to hold an election for King in England tomorrow, the incumbent would distance all others at the polls.

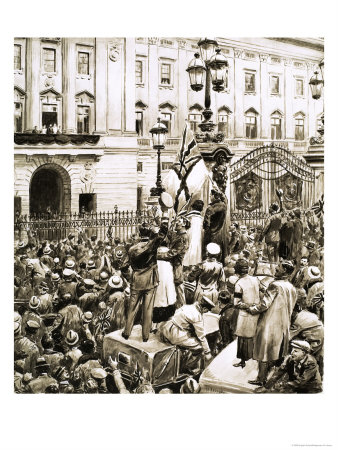

At a quarter to 11 there were no signs of special commotion before the palace. A few idlers had gathered to watch the ceremony of changing the guard. The only flag in sight was the royal standard. At 11 o’clock, precisely, a typewritten copy of the Premier’s announcement that hostilities had ceased was hung outside the railings and then the maroons exploded.

The crowds began to gather, coming from all directions like bees in a swarm. Many had flags. Men on horseback came from somewhere and reined up before the palace. Taxicabs and motor cars came along and people who wanted to see better began to climb on the roofs. Within a few minutes many thousands had assembled and they began to call for the King.

At 11:15 King George, in the uniform of an Admiral, appeared on the balcony. The Queen, bareheaded and wearing a fur coat, was with him. The Duke of Connaught came too, and the Princess Mary. The soldiers presented arms and the Irish Guards’ band played the national anthem and the crowd solemnly took up the slow refrain. Then the band played “Rule Britannia.” The people sang again and flags began to wave. They were nearly all British flags. The King removed his cap and his loyal subjects cheered, and someone proposed a groan for the Kaiser, which was given sonorously, and the ruler of Great Britain and all the Indies donned his cap and the royal group went back into the palace.

The throngs, pleased and decorously animated, moved away, but their places were taken by other thousands, and the whole performance was repeated. At one of his appearances the King was graciously inspired to make a speech. It consisted of only a sentence or two, but it was all right and the people applauded rapturously.

Later, the King decided to drive through the city. He was accompanied by the Queen and the Princess Mary. Rain was falling, but nobody in England minds rain. It was a triumphal procession. Everywhere at central points had gathered many thousands to welcome their majesties. One mighty group was at Victoria Memorial; another at Admiralty Arch; another at Ludgate Circus; and still another at Mansion House, where the Lord Mayor, in his official robes of black and gold, was on hand to receive the royal pair.

The streets were encompassed all the way by many people. Here and there was a police officer, but the police had no difficulty with the crowds. There was no special or unusual guard for the King and Queen, only a few outriders. They have no fear, evidently, in England, that anything untoward will happen to the Crown, through the act of a madman, or the deliberate deed of a regicide. A policeman’s baton is enough. The English respect authority and obey it.

On the succeeding day it was announced that the King and Queen would attend a thanksgiving service at St. Paul’s Cathedral. The street scenes of the previous day were repeated during the progress of the royal couple to the magnificent center of worship. It is a noble and wonderful shrine, with a fit setting for occasions of vast importance. Great bells rang and a mighty concourse gathered, and a solemn and beautiful ceremony was conducted in commemoration of the triumph of the allied cause. The climax of the peace celebration was of course reached in the movements of the King and Queen; but these were merely the outstanding events. It is a fact, however, that it was everybody’s affair, and he took his own way to show his joy that the end of the long and weary road had been reached at last.

The Strand, ending in Trafalgar Square, the heart of London, is the most popular thoroughfare in the city. It attracts the visiting soldiers, and the soldiers make up a great part of the ordinary moving crowds. The Strand is about as wide as Washington street, and it may easily become congested. But somehow the people get along and the traffic proceeds and nothing much ever happens.

When the joy-making began, the crowds took possession not only of the Strand, but of all available vehicles. A favorite adventure of men and women was to commandeer a taxicab and to pile in and on anywhere, preferably on top. One car, with a prescribed capacity for four, had exactly twenty-seven persons sardined in its not-too-ample proportions. Then there were lorries–automobile trucks–crowded with soldiers, civilians and girls, all waving flags and singing or shouting.

Soldiers formed in procession and marched along. After a while they turned about and went the other way. Girls in uniform– munitions workers–appeared in large numbers, and walked along, arm-in-arm with the men in khaki. Flags were plentiful, mostly British, with a fair proportion of American, French and Belgian. But the unvarnished truth is that Britain was celebrating a British victory. Well, why not? They were polite enough to make reasonable concessions to their allies–whenever they thought of it.

A group of Americans standing on the walk, somewhat uncertainly displaying American flags, were frequently cheered by the passing revelers. Once a lot of Canadians came in sight, and some of them broke from their fellows, and came over and asked the Americans for the flags, which were promptly given them.

At another time, a great lorry with perhaps 50 passengers aboard, stopped in front of an American with a bandaged head, waving Old Glory, and gave him three rousing cheers. They thought, doubtless that he was a hero of the war, with a wound honorably won in battle. He did not undeceive them. The day went on with no diminution of the crowds or moderation of the excitement. Apparently it increased rather than diminished. Business was wholly suspended, except in the restaurants and hotels, and the metropolis gave itself up to merry-making. Yet it was mainly an unorganized, though orderly, spectacle of movement, without any great variety of stunts or picturesque Incidents. Perhaps the crowd did not know how to do things as they do in America; or perhaps it was merely content to go and go and go–and then come back.

There was little drinking or drunkenness, apparently, in the streets, though there was plenty, and to spare, later in the great hotels. Possibly the crowd was sober because intoxication costs money nowadays in England; or perhaps it was not in the humor to drink. But the gay assemblies within the walls of the restaurants had no such scruples. There was much drinking, much noise, much laxity, a complete departure from the innocent gayety of the streets.

The celebration did not end on Monday night. But it started up again on Tuesday and continued through the week. When London celebrates it celebrates. There is no question about it. Occasionally the crowd broke bounds. At Piccadilly Circus there was a great bonfire made up of big signboards taken by force from passing omnibuses. The same thing occurred at Trafalgar Square, where the effort to subdue the flames by water from a firemen’s hose led to cracking the stones at the foundation of the Nelson monument, making a serious disfigurement of that splendid column. But such scenes were rare.

London had not sobered down, or up, when the editors left, on a Friday. It was said that Saturday night would probably see the culmination of an entire week’s festivities in a great saturnalia in which the whole population would join.

It is pleasant to contemplate the comparative calm of a voyage at sea, even in Winter time, when storms abound, but submarines do not.

— Edgar Bramwell Piper, Somewhere Near the War (1919)

Your first two photos are unbelievable… it seems as if all 7 million Londoners had squashed into the camera view. It was only when they really believed that the war was really over that “London let itself loose in a spontaneous and mighty demonstration”. Even then, so many boys were never going to come home, or were going to come home in pieces.

Contrast this scene with 1914 when fit, healthy lads marched off proudly, expecting to be home by that Christmas. How wrong they were 🙁

They are indeed! The last line in Lady Cynthia Asquith’s WWI diaries never fails to choke me up: : “I am beginning to rub my eyes at the prospect of peace. I think it will require more courage than anything that has gone before. It isn’t until one leaves off spinning round that one realises how giddy one is. One will have to look at long vistas again, instead of short ones, and one will at last fully recognise that the dead are not only dead for the duration of war.”

Awesome pictures, Evangeline, thank you for sharing them and some history. I’m so glad I found your blog … will follow on mine. Thank you. <3

You are very welcome!