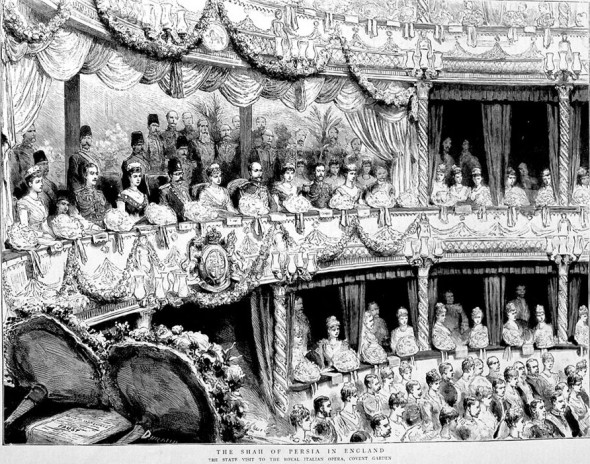

When the Countess de Grey was not indulging in the opulent parties and affairs of the Marlborough House Set, she turned her attentions to reversing the decline of the Royal Italian Opera House (colloquially known as “Covent Garden”).

By the 1880s, opera in England was lackluster and unexciting, and the Gye family, who managed the opera house, and M. Gatti, its leasee (who had 63 years left in the lease), were burdened by crushing debt. Matters were so poor, the 1886 opera season was only saved at the last minute by impresario Signor Lago and a troupe of artists, who mounted middling productions for that season and the one that followed. The steep decline no doubt shocked high society, since the opening of the opera season at Covent Garden marked the official start of the London Season, and the plight of the opera house likely caught the sensitive, musically-inclined Lady de Grey’s attention in particular.

Under her influence, as well as that of Lady Charles Beresford, impresario Augustus Harris was brought in to manage Covent Garden. Harris, whose luxurious operas brought a breath of fresh air to Drury Lane, and launched the international careers of the de Reske brothers, Minnie Hauk, and Lillian Nordica. But Drury Lane was not fashionable for opera, so the creme de la creme of late Victorian high society only watched his successes from a distance. Nevertheless, Harris’s triumphant launch of Lohengrin in 1887, starring Jean and Edouard de Reske, put him £16,000 in the hole!

The following year, Lady de Grey and Lady Charles Beresford took him in hand to secure the lease of Covent Garden–but under one condition: that the ladies (and Mr. H.V. Higgins, Gladys’s brother-in-law) secure half the boxes for the upcoming season. The ladies and Higgins did one better–all of the boxes were taken by their friends and acquaintances in high society, thus setting up the system of subscription to the opera (which also kept the leasing boxes exclusive).

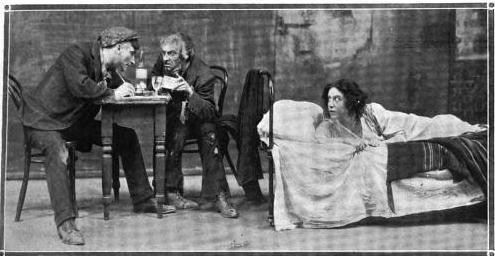

The 1888 opera season saw a packed house of society leaders and the Prince and Princess of Wales, and the (re)introduction of Nellie Melba. She had performed two years previously under her own name of Mrs. Nellie Armstrong at Prince’s Hall, but to little acclaim, which made her reluctant to return. Augustus Harris remembered her talent, and hired her for his first season. The reaction to her performance was encouraging, but Harris’s offer of a small part offended her and she vowed never to return to England. In stepped Gladys de Grey, who managed to persuade the Australian soprano to return to Covent Garden and persuade Harris to grant Melba a meatier role. Nellie Melba’s second debut at Covent Garden, in Roméo et Juliette opposite Jean de Rezke, launched her into the operatic stratosphere, literally and figuratively. She also now counted Gladys de Grey a lifelong friend.

Gladys brought her reputation in opera circles to her husband’s country house, Coombe Court, where her dinner parties were illuminated by opera singers, artists, and writers, thus beginning the breaking down of barriers between performers and society (before then, artists were invited to perform at dinners and house parties, but were considered on the same level as servants). Gladys’s real coup was bringing the Ballet Russes to London in the 1910s. The Ballet Russes, under the management of Sergei Diaghilev, had already astounded Parisian society with their “primitive” music and costumes, and Gladys, always daring and besotted with lavish spectacle, was determined to introduce them to London society. The company “arrived in London in 1911, billed as the Imperial Russian Ballet,” and their performance was added to the official program of celebrations marking George V’s coronation year. The ballet and the sets and costumes designed by Léon Bakst–shocking, erotic, and foreign–, ignited society and fashion; overnight it seemed ladies changed from languid, delicate colors and soft, curving silhouettes to bright, garish colors and angular, exotic types.

The war placed a temporary halt on Covent Garden opera, and Lady de Grey turned her energies to war efforts until her death in late 1917. Though she died before Covent Garden could resume its seasons post-WWI, Gladys de Grey left an indelible mark on opera and ballet in London society, and opened the door for aristocratic patronage of the arts and facilitated the meeting of high society and talented artists on equal footing.

Cited

The Victorian Visitors: Culture Shock in Nineteenth-Century Britain by Rupert Christiansen

The Royal Opera House in the Twentieth Century by Frances Donaldson

“Modern Musical Celebrities,” The Century, 1903

Women and Marriage in Nineteenth-Century England by Joan Perkin

1913:The Defiant Swan Song by Virginia Cowles

Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes by Lynn Garafola

Visit

Diaghilev and the Ballets Russes, 1909–1929: When Art Danced with Music – National Gallery of Art, East Building Mezzanine. May 12 – October 6, 2013. Organized by the Victoria and Albert Museum, London, in collaboration with the National Gallery of Art, Washington.