America at the turn of the century stood at a crossroads. It had conquered the West, proved its might with the Spanish-American War, and along with Germany, had become a global supplier of goods and technologies. Yet, because of its youth, it remained a small player on an international scope, forced to bow to the centuries of expertise and might of its European peers. With the inadvertent placement of Theodore Roosevelt in the White House, an energetic, youthful, and charismatic man not unlike the country he led, the United States was poised to snatch the attention away from Europe and to show she was nothing less than an equal—perhaps even a superior—to the Old Country.

Since the 1820s, the Monroe Doctrine had become a defining force in American foreign policy. Back then, in the midst of Latin American countries throwing off the yoke of the Spanish Empire, the United States was concerned of the possibility of another European power asserting a claim on the Americas, and President James Monroe stated “that further efforts by European countries to colonize land or interfere with states in the Americas would be viewed as acts of aggression requiring U.S. intervention.” In short, it basically gave the United States carte blanche to assert its own claims in the Americas.

After the Venezuelan Crisis of 1902, in which Germany, Italy and Britain formed a blockade of the country in retaliation for unpaid debts and sparked a minor armed conflict. The presence of European gunboats in American waters was very unpopular in the United States, and as President Roosevelt pressured the European powers to drop the blockade, he stationed naval forces in Puerto Rico, “to ensure ‘the respect of Monroe doctrine’ and the compliance of the parties in question.” This action formed the nucleus of his extension to the Monroe Doctrine, the “Roosevelt Corollary,” in which he “asserted a right of the United States to intervene to ‘stabilize’ the economic affairs of small states in the Caribbean and Central America if they were unable to pay their international debts.”

In the meantime, expansion of the United States provoked the need for a speedier route for ships to travel from the Atlantic Ocean to the Pacific. Despite the rapid advancement of technology during the 19th century, ships continued to reach the Pacific Ocean from the Atlantic through the centuries old route down South America and the Strait of Magellan. The earliest mention of a canal through the isthmus of what is now Panama was in 1534, when when Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor and King of Spain ordered a survey for a route through Panama that would ease the voyage for ships traveling to and from Spain and Peru. The Kingdom of Scotland launched the ill-fated Darién scheme in 1698 in hope of setting up and overland trade route and becoming a world power, but it was plagued by the generally inhospitable conditions, and abandoned in July of 1699. Alessandro Malaspina launched an expedition in 1788–1793, and demonstrated the feasibility of a canal and outlined plans for its construction. These attempts were but a few of the many hopes and dreams of building a canal, and mid-19th century engineers and powers made do with the Panama Railway, which opened in 1855.

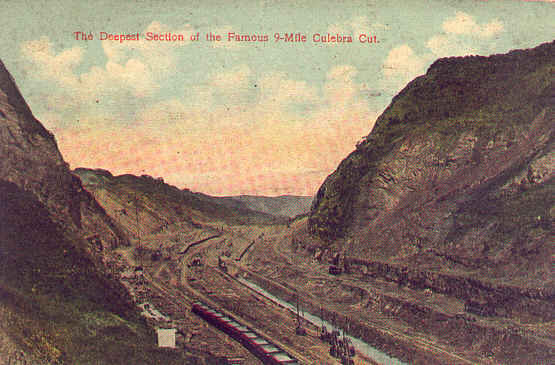

When in the 1880s, Ferdinand de Lesseps, developer of the Suez Canal, undertook the task of constructing a canal across the isthmus, he began with much fanfare and triumph. His role in the opening of the Suez Canal, which shortened the route to Asia and Australasia, made him a French national hero and not only did the French government have full faith in his abilities, but the French public, and the newly-formed Panama Canal Company became the investment to pour one’s money into in certainty of obtaining huge returns. Unfortunately, the French company rushed into isthmus with no knowledge of the area’s climate or of the geographic differences between it and the dry, flat land from which the Suez Canal was cut. Construction began in 1880, and by the end of the decade, thousands of workers had died, landslides had wiped out what small work had been accomplished, and the scandal back in France, when the revelation of bribes and swindles emerged—egged on by an antisemitic press, pinning the blame on Jewish financiers—both de Lesseps and the Panama Canal Company were finished.

When in the 1880s, Ferdinand de Lesseps, developer of the Suez Canal, undertook the task of constructing a canal across the isthmus, he began with much fanfare and triumph. His role in the opening of the Suez Canal, which shortened the route to Asia and Australasia, made him a French national hero and not only did the French government have full faith in his abilities, but the French public, and the newly-formed Panama Canal Company became the investment to pour one’s money into in certainty of obtaining huge returns. Unfortunately, the French company rushed into isthmus with no knowledge of the area’s climate or of the geographic differences between it and the dry, flat land from which the Suez Canal was cut. Construction began in 1880, and by the end of the decade, thousands of workers had died, landslides had wiped out what small work had been accomplished, and the scandal back in France, when the revelation of bribes and swindles emerged—egged on by an antisemitic press, pinning the blame on Jewish financiers—both de Lesseps and the Panama Canal Company were finished.

By this time, various interests in the United States expressed interest in building a canal across the isthmus, with some favoring a route across Nicaragua and others advocating the purchase of the French interests in Panama. A commission was set up in 1899 to determine which area was best, but when the Nicaraguan deal was settled, it was discovered that the United States would have no legal jurisdiction over the canal. Those urging for the canal to be built in Panama pointed out the obvious choice; however, the French and Colombian company hiked up the price for the isthmus, and refusing to pay such an exorbitant price, the United States instead “engineered a revolution.” With the support of the U.S. Navy, Panama revolted against Colombia on November 3, 1903 and formed a republic. The new republic of Panama received $10 million from the U.S., an annual payment of $250,000, and guarantees of independence. The United States gained the rights to the canal strip “in perpetuity”

By this time, various interests in the United States expressed interest in building a canal across the isthmus, with some favoring a route across Nicaragua and others advocating the purchase of the French interests in Panama. A commission was set up in 1899 to determine which area was best, but when the Nicaraguan deal was settled, it was discovered that the United States would have no legal jurisdiction over the canal. Those urging for the canal to be built in Panama pointed out the obvious choice; however, the French and Colombian company hiked up the price for the isthmus, and refusing to pay such an exorbitant price, the United States instead “engineered a revolution.” With the support of the U.S. Navy, Panama revolted against Colombia on November 3, 1903 and formed a republic. The new republic of Panama received $10 million from the U.S., an annual payment of $250,000, and guarantees of independence. The United States gained the rights to the canal strip “in perpetuity”

Construction of the canal began in 1904 and it was not completed until 1913. When the canal finally opened in August 15, 1914 with the passage of the cargo ship SS Ancon, it had cost the United States approximately $375 million and 5,609 lives. Despite this, the sheer impressiveness of the Panama Canal signaled the emergence of America as a global superpower, and the Canal quickly became a popular course for leisurely steamship cruises from one coast of the United States to the other. The following year saw the Panama-Pacific International Exposition, which celebrated both the opening of the Canal and the rebirth of San Francisco less than a decade after its devastating earthquake. For more information on the construction of the Panama Canal, tune in to PBS’s American Experience special Monday, January 24th at 9 p.m. Showcasing a fascinating cast of characters, commentary by historians, and first-hand accounts from canal workers (and their descendants), Panama Canal is a show as epic as its topic.

Construction of the canal began in 1904 and it was not completed until 1913. When the canal finally opened in August 15, 1914 with the passage of the cargo ship SS Ancon, it had cost the United States approximately $375 million and 5,609 lives. Despite this, the sheer impressiveness of the Panama Canal signaled the emergence of America as a global superpower, and the Canal quickly became a popular course for leisurely steamship cruises from one coast of the United States to the other. The following year saw the Panama-Pacific International Exposition, which celebrated both the opening of the Canal and the rebirth of San Francisco less than a decade after its devastating earthquake. For more information on the construction of the Panama Canal, tune in to PBS’s American Experience special Monday, January 24th at 9 p.m. Showcasing a fascinating cast of characters, commentary by historians, and first-hand accounts from canal workers (and their descendants), Panama Canal is a show as epic as its topic.

Further Reading:

The Panama Canal by J. Saxon Mills

Zone Policeman 88; a close range study of the Panama canal and its workers by Harry Franck

Canal Museum

(FTC disclosure: A DVD of the documentary was provided to the reviewer by the production company. The writer did not pay for this DVD but received it free.)