At the beginning of Edward VII’s nine year reign, the motorcar was simply a status symbol that only the very rich could afford to purchase and maintain. The horse, generally cheaper and familiar to the population, continued to dominate everyday travel and transportation, but by 1910, equine transport had become almost obsolete.

The manufacture of motorcars originated in France and Germany in the 1880s, where Continental inventors experimented with the internal combustion engine. Engineers such as Edmund Benz, Gottlieb Daimler, Nikolaus Otto, Wilhelm Maybach, and Alphonse Beau de Rochas developed and patented a variety of engines during the 1860s through 1880s, but the promise of the motorcar did not bear fruition until the mid-1880s, when Edmund Benz designed a “four-stroke engine that was used in his automobiles, which were developed in 1885, patented in 1886, and became the first automobiles in production.” Gottlieb Daimler, a German engineer, patented his own version in 1885, and further production of engines for self-propelled vehicles continued into the early-1890s.

The modern automobile was built in France by Panhard et Levassor in 1890. This model had its engine in the front under a bonnet (hood), a chassis (body) much like the chassis of today, a sliding gear transmission, clutch and pedal breaks and a foot accelerator. Panhard had serious competition from Peugeot, also French, and a growing number of European and American manufacturers during the first half of the 1890s. Meanwhile, Britain’s development of comparable technology was paralyzed by the Red Flag Act of 1865. Its crippling clause–“Any vehicle on the public highway, other than a horse-drawn vehicle, must be preceded by a man carrying a red flag in day and a red lantern at night, to warn oncoming traffic of the vehicle behind him.”–had been placed into affect by the railroads, who wished to halt the rising popularity of the steam-cars in the 1850s.

Because of the presence of the flag-carrying man, the speed limit was restricted to four to five miles per hour, a crawling pace that was bound to discourage any sporting gentleman. In 1895, the Honorable Evelyn Ellis brought his French-made 4 hp Panhard machine to England in defiance of the act, and when it was repealed in 1896 and the speed limit increased to fourteen miles per hour, new motor enthusiasts commemorated the repeal of the hated Red Flag Act with a London to Brighton run on November 14th of that year.

While the original English motorists were typically wealthy sportsman, it wasn’t until Edward VII took up motoring (with relish) that the motorcar began to gain precedence over the horse and carriage with the Marlborough House Set. The King owned several automobiles, all painted in his own royal claret color, which he took for speedy drives up and down country roads. He was an impatient and excited driver, loudly encouraging his chauffeur to pass everything and everyone on the road, regardless of their speed, size and status. It was a very frequent occurrence for a waggon lumbering down a road to Sandringham to be upset due to the careless speed of the King of England. However, he always politely proclaimed oncoming traffic of his imminent arrival with the honk of his four-key hornet horn, which the superintendent of the royal cars, who sat in front, had to play as the king’s car zoomed along.

Surprisingly, he refused to allow his wife, Queen Alexandra, to own a motor of her own. It was only after Alexandra borrowed motors from friends, much to the anxiety of the Court, that Edward was eventually persuaded to allow her an automobile of her own. Alexandra was the original backseat driver, growing notorious for prodding her driver violently in the back with her parasol, shouting directions and “helpful” orders whenever a dog, or child, or anything else crossed their way.

The Queen’s ownership of a motorcar made the machine imminently respectable, and many women took to the sport with as much alacrity as their male counterparts. The Baroness Campbell von Laurentz for example, took up motoring in 1900 and soon began to travel widely, contributing articles to such publications as Car Illustrated, Autocar, Ladies’ Field, and Heart and Home. The baroness, indefatigable in her love for the sport, was also an inventor, designing her own solution to the problem of transporting luggage in a car that provided accommodation to passengers alone that plagued all early motorists. She designed two square fiber boxes to fit on the luggage grid at the rear. They went on the grid with “a piece of canvas underneath and over the top, a tailored cover in proofed canvas, leather-bound.” Following in the footsteps of the baroness were Mrs. Bernard Weguelin, Mrs. Claude Watney and Miss Mee of Chichester Cathedral, who, in 1905, became the first lady to pass “the examination in driving and general proficiency set by the Royal Automobile Club for the owners of cars.”

Due to the absence of hoods or windscreens, motoring called for special clothing. Fabrics such as tweed and cloth were out, for the wind whipped them out into balloons. Loose topcoats in leather, or special motoring coats from Burberry or Aquascutum acted as protection from weather and cold, with the stipulation that the coats should button closely around the wrist. For women, long fur-lined leather or cloth coats for winter and long linen or alpaca dust coats for summer were preferred. Oil smuts could be a problem so women wore flat hats tied on with large, thick veils. For men, double-breasted reefer jackets, buttoned high with small turn down collars, wind cuffs with straps, trousers bound tightly around the ankles, and yachting cap and gloves. For the winter, leather coats, helmets and fur-lined coats and twill holland or silk dust coats were recommended. During a bout of rain, experts advised the adoption of a garment shaped like a bell tent, from which the rain would run. Goggles were also a must.

Socially, the motorcar increased the amount of time spent on leisure activities. No longer were weekend parties hasty, hectic affairs as the motorcar allowed parties to speed from London to the countryside for what hostesses fondly called “Saturday-to-Mondays”. Affairs were carried about more easily, as a wife or husband was now able to drive to a quick rendezvous with a lover in an inn or tavern and back before their unsuspecting spouse could comment upon their absence. General travel was made easier not only by the motorcar, but also by the increased network of tramways that made the countryside more available to Londoners, while railroads, ever vigilant, ran seaside excursions. Enthusiastic motorists added another form of leisure to the motorcar in the guise of touring. Countless books were published between the years 1896 and 1914, recounting motor tours in both remote and accessible places like the Hebrides and France, as well as in places uncharted by the motorcar, such as Tunisia, China or Siberia. This new form of holidaying was incorporated into the itineraries of trusted travel agents such as Thomas Cook & Son among others, who provided maps of possible touring routes as well as the locations of petrol stations.

Soon, the 1900s became the era of speed. The first motorcar race was held in 1894, and was quickly followed by the establishment of Grand Prix from Le Mans, France to Daytona Beach, Florida, where, in 1904, Willie K. Vanderbilt, Jr. clocked up to 92 mph in his 90 hp Mercedes. The Peking-Paris race of 1907 was won by the journalist Barzini, the Prince Borghese, and the mechanic Ettore Guizzardi, who drove an Italian model called the Itala. Despite the success of British drivers in the early races, the sport was impossible on the British Isles since racing on public roads was illegal. This caused British drivers to race on the Continent or in Ireland (i.e. the Gordon Bennett race of 1903). Hugh Locke-King, a wealthy landowner, was aided by a group of wealthy friends to propose the construction of a racing course. The result was Brooklands track, a huge oval circuit with banked corners. Work was completed in 1907, and the world had its first purpose built race-track. Other nations would soon follow suit.

The motorcar also introduced a new lexicon of terminology into the English language. One kept one’s car not in a garage, which was French and therefore rather naughty, but in a motor stable. A driver was not yet called a chauffeur, but a mechanic, for he often doubled as an actual mechanic as most motoring gentlemen found it beneath them to tinker beneath the bonnet. It also altered the patterns of servants and functions of the home, which had remained unchanged for centuries. Stablehands and coachmen were either pensioned off or taught to drive, while mews were either converted into motor stables or into small, attractive residences, and horses were sold and carriages dismantled.

As with everything, there was a dark side to the motorcar. A dark, expensive side. Early motoring demanded both time and money–Money because motoring was an expensive occupation, while time was needed for running repairs, not only for a succession of tyre punctures, but for the continual mechanical faults of varying severity. A motorist who drove on a daily basis could spend at least an hour a day cleaning, oiling and adjusting. Tyres cost ₤25. 15s a pair and were always bursting. Because there were few instruments to maintain the car, the first sign of the engine overheating was the smell of burning paint. Pistons were easily ruined and some more powerful cars guzzled as much oil as petrol. While the price of petrol varied enormously from a copper or two to 1s.3d a gallon (depending on the greed of the garage proprietor), filling stations were few and far between, causing drivers to depend on a steady supply on hand, especially as there were few others on the road to assist a stranded motorist.

Until 1903, there had been no numbers or licenses. From henceforth every car was required to carry a registration number. By the end of the year, 8,500 motors were licensed in Britain (the registration number A1 allocated to Earl Russell), which proved that the motorcar in Britain was no passing craze of the idle rich. At the beginning of Edward’s reign, London transportation was exactly as Dickens knew it; that is, the horse provided the locomotion as it had for centuries. However, motorbuses were first licensed by the police authorities in 1904, and by 1910, they had displaced 22,000 horses and 2,200 horse omnibuses. A few displaced drivers continued their trade, becoming known as “pirates” because of their cut-rate prices, and continued to run as late as 1916. Motorcabs, informally known as “taxis” were introduced to London in 1907 after the General Motor-cab Company placed one hundred vehicles on the road. By the end of 1907 there were 723 taxis in London, a figure that quadrupled the in the next year. By 1910, there were 4,941 taxis, though there remained on the streets, 1,200 hansom cabs (affectionately called “gondolas of the street” by Disraeli) and 2,500 horse-drawn four-wheelers.

Until 1903, there had been no numbers or licenses. From henceforth every car was required to carry a registration number. By the end of the year, 8,500 motors were licensed in Britain (the registration number A1 allocated to Earl Russell), which proved that the motorcar in Britain was no passing craze of the idle rich. At the beginning of Edward’s reign, London transportation was exactly as Dickens knew it; that is, the horse provided the locomotion as it had for centuries. However, motorbuses were first licensed by the police authorities in 1904, and by 1910, they had displaced 22,000 horses and 2,200 horse omnibuses. A few displaced drivers continued their trade, becoming known as “pirates” because of their cut-rate prices, and continued to run as late as 1916. Motorcabs, informally known as “taxis” were introduced to London in 1907 after the General Motor-cab Company placed one hundred vehicles on the road. By the end of 1907 there were 723 taxis in London, a figure that quadrupled the in the next year. By 1910, there were 4,941 taxis, though there remained on the streets, 1,200 hansom cabs (affectionately called “gondolas of the street” by Disraeli) and 2,500 horse-drawn four-wheelers.

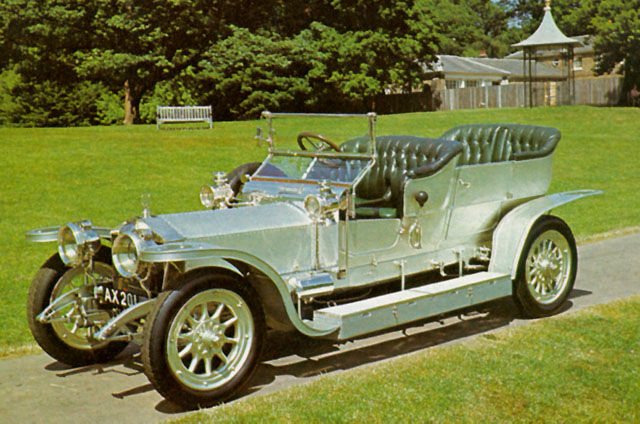

The motorcar revolution was seen as similar to the railway revolution. Nevertheless, there was one main difference: the railway had been an instrument of democracy, while the car represented the private ostentation at its most arrogant, the final triumph of the haves over the have-nots. The ultimate in Edwardian status symbol was the 1911 Rolls Royce “Silver Ghost”, which cost ₤1,154, more than what most people earned in ten years.

Further Reading:

Behind the Wheel: The Magic and Manners of Early Motoring by Lord Montagu of Beaulieu & F. Wilson McComb

The Edwardians by Charles Petrie

The Edwardian era was so short, it is difficult to imagine it as a time of major social change. Yet it clearly was.

King Edward VII could have insisted that the horse and carriage was more regal, more traditional and more British than any new fangled foreign machinery. Yet he took up motoring so enthusiastically that the motorcar began to gain precedence over the horse and carriage with THE trend setters – Marlborough House Set.

No wonder the era was one of change. For these well heeled and well connected families, you mentioned at least two critical changes:

a] fashionable clothing became car-appropriate, as well as smart and

b] parties could easily get out of London to the countryside for Saturday-to-Monday weekends.

I created another link to Church Parades in Hyde Park, many thanks

Hels

You’ve hit the nail on the head. Society had actually become society with a little “s” in the Edwardian era, as greater mobility allowed sets to go their own way. Even the London Season and court life had lost a bit of its prestige, particularly after Edward VII died, and George and Mary instituted a much quieter life. I’m reading two books about the “Souls,” and the goings-on within that clique really expands what I initially believed to be true about Edwardian high society.