Belle Epoque France was relatively free of the hypocrisy of Edwardian England, and there, the courtesan flourished. The exploits, the rivalries, the fashion, the lovers, and the wealth of Les Grand Horizontals were given equal coverage as the doings of Tout Paris, and in fact, where the courtesans led, the smartest of the smart set usually followed. Such was the status courtesans commanded within Parisian society, their presence was expected in certain settings that were the prerogative of the upper class. They drove in the Bois every afternoon during the Paris Season, they attended the races at Auteuil and Longchamps, they watched the polo matches at Bagatelle, they participated in charity bazaars, made an appearance at the Opera on Mondays, and even supped at the same after-theater restaurants as the aristocracy. In short, the courtesan was as close to an aristocracy in their own milieu as possible.

Belle Epoque France was relatively free of the hypocrisy of Edwardian England, and there, the courtesan flourished. The exploits, the rivalries, the fashion, the lovers, and the wealth of Les Grand Horizontals were given equal coverage as the doings of Tout Paris, and in fact, where the courtesans led, the smartest of the smart set usually followed. Such was the status courtesans commanded within Parisian society, their presence was expected in certain settings that were the prerogative of the upper class. They drove in the Bois every afternoon during the Paris Season, they attended the races at Auteuil and Longchamps, they watched the polo matches at Bagatelle, they participated in charity bazaars, made an appearance at the Opera on Mondays, and even supped at the same after-theater restaurants as the aristocracy. In short, the courtesan was as close to an aristocracy in their own milieu as possible.

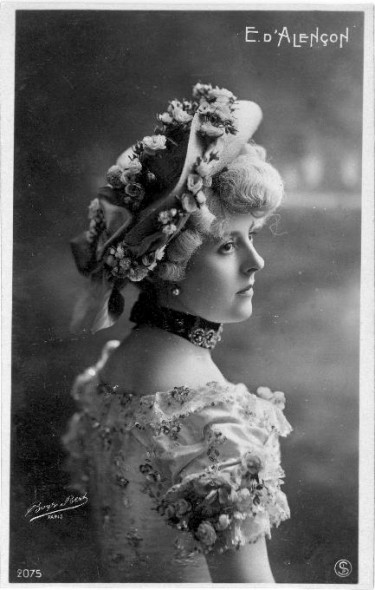

The three most notorious courtesans of the age–known as the Les Grandes Trois–were Emilienne d’Alençon, Liane de Pougy, and Caroline Otero, called “La Belle Otero.” Like many other top courtesans and middling prostitutes, the three women earned the bulk of their infamy as actresses in such places as the Folies Bergère. Ironically, while this gave them a measure of respectability, it also reinforced the idea that all actresses were prostitutes!

Liane de Pougy was the trio’s undisputed star, and her cool beauty and faultless manners earned her the moniker “Notre courtisane nationale.” Like many courtesans, her origins were humble (her father was an army officer), and an early and unwanted marriage lingered in her past. As a divorcee by age of nineteen, young Liane (then Anne-Marie Pourpe) supported herself by giving piano and English lessons. That is, until she realized life was more glamorous and lucrative as a prostitute. She snatched the public’s attention when she watched the Grand Prix with the Marquis MacMahon by her side, but she solidified her career when, on her first night at the Folies Bergère, she sent a note to the visiting Prince of Wales requesting he watch her Paris debut. He did, and his approval made her an overnight sensation with the Jockey Club set. Jewels, carriages, homes, and art came pouring in, and the new era of the courtesan began.

Liane’s bitterest rival was Caroline Otero, a Spanish dancer who was known to “jump up on a table at Maxim’s and go into a writhing fandango so sensual that every man in the room felt she was making love to him.” La Belle Otero, the illegitimate child of a Greek nobleman and a Cadiz gypsy, began her career as a dancer at age twelve and her career as a prostitute at fourteen. By fifteen, she juggled three Andalusian grandees and an Italian husband who was, in Caroline’s words, “as handsome as Bizet’s Toreador.” However, she soon abandoned this handsome husband and began performing in Marseilles caf-concs before making her way to Monte Carlo. She won a small fortune at the tables and quickly set herself up in style in Paris. La Belle Otero made her way to the Folies Bergère in the 1890s, where she blazed a sensuous path to stardom.

Liane’s bitterest rival was Caroline Otero, a Spanish dancer who was known to “jump up on a table at Maxim’s and go into a writhing fandango so sensual that every man in the room felt she was making love to him.” La Belle Otero, the illegitimate child of a Greek nobleman and a Cadiz gypsy, began her career as a dancer at age twelve and her career as a prostitute at fourteen. By fifteen, she juggled three Andalusian grandees and an Italian husband who was, in Caroline’s words, “as handsome as Bizet’s Toreador.” However, she soon abandoned this handsome husband and began performing in Marseilles caf-concs before making her way to Monte Carlo. She won a small fortune at the tables and quickly set herself up in style in Paris. La Belle Otero made her way to the Folies Bergère in the 1890s, where she blazed a sensuous path to stardom.

Emilienne d’Alençon’s career was much quieter, but also much more lucrative, since she was the object of obsession for King Leopold II of the Belgians and Jacques d’Uzès, son of the Duchesse d’Uzès, heiress to the Veuve Clicquot fortune. So besotted was the King, he invited her to accompany him on his royal visits and introduced her to Edward VII as the Countess Songeon. So besotted was young Jacques, he gave her the Uzès family jewels. The latter liaison ended when the Duchesse packed her son off to the Congo, where he died in 1893. Emilienne, born Émilie André, began her career at fifteen when she ran away from home with a gypsy violinist. She managed to enter the Paris Conservatory with aspirations to be an actress, but left after a year, later appearing at the Circus d’Ete in an act with trained rabbits. This act earned her a place at the Folies Bergère, where her rabbits were tinted bright pink and wore paper ruffs. She of course became more than a mere rabbit tamer, embarking upon her career with the aforementioned gentlemen. Incidentally, she was also the lover of Etienne Balsan when the dashing sportsman met a young Gabrielle Chanel in the mid-1900s.

The most important element of a courtesan’s reputation was her jewelry, and they owned a lot of it. During the duration of their time at the top, a courtesan could expect to collect millions, if not tens of millions of francs, worth of diamonds, pearls, sapphires, gold, rubies, and emeralds. They were mounted in the typical settings of the day–dog collars, stomachers, tiaras, bracelets, necklaces, parures, earrings, etc–but obviously much more ostentatious than that worn by a duchess or a princess. The most startling display of wealth was a showdown in Maxim’s between Liane de Pougy and Caroline Otero. This restaurant was a courtesan’s domain, where no respectable woman was allowed or would even admit to acknowledging its existence, and the right entrance signaled one’s place in the hierarchy. One night, La Belle Otero entered Maxim’s in an evening gown with a plunging neckline and her entire collection of jewels. They blazed at her neck and ears, in her hair, on her bosom, her arm, hands and waist, and one or two sparkled on her ankles. The crowd was stunned, but they were even more stunned when Liane–tipped off by a friend–entered a few minutes later in a simple white evening gown. In her wake was her lady’s maid who carried a velvet cushion on which sat a jewelry box weighted with jewels.

The most important element of a courtesan’s reputation was her jewelry, and they owned a lot of it. During the duration of their time at the top, a courtesan could expect to collect millions, if not tens of millions of francs, worth of diamonds, pearls, sapphires, gold, rubies, and emeralds. They were mounted in the typical settings of the day–dog collars, stomachers, tiaras, bracelets, necklaces, parures, earrings, etc–but obviously much more ostentatious than that worn by a duchess or a princess. The most startling display of wealth was a showdown in Maxim’s between Liane de Pougy and Caroline Otero. This restaurant was a courtesan’s domain, where no respectable woman was allowed or would even admit to acknowledging its existence, and the right entrance signaled one’s place in the hierarchy. One night, La Belle Otero entered Maxim’s in an evening gown with a plunging neckline and her entire collection of jewels. They blazed at her neck and ears, in her hair, on her bosom, her arm, hands and waist, and one or two sparkled on her ankles. The crowd was stunned, but they were even more stunned when Liane–tipped off by a friend–entered a few minutes later in a simple white evening gown. In her wake was her lady’s maid who carried a velvet cushion on which sat a jewelry box weighted with jewels.

She won that round.

Despite the glamor and mystique that surrounded the courtesan, her life was not easy. Many aspired to the rank, but ended up in bitter poverty, and even those who reached the pinnacle of this career could find themselves cast off at the whim of their lover, or worse, bankrupt by a spendthrift protector. Nevertheless, this class of women were able to live a public life of luxury and notoriety for however long they captured the public’s attention, and for many women, this was preferable to a gray, dull life of toil and obscurity.

Further Reading:

Grandes Horizontales: The Lives and Legends of Four Nineteenth-Century Courtesans by Virginia Rounding

The Book of the Courtesans: A Catalogue of Their Virtues by Susan Griffin

Elegant wits and grand horizontals: a sparkling panorama of “la belle epoque,” its gilded society, irrepressible wits and splendid courtesans by Cornelia Otis Skinner

Love this post! The photographs of the women are so great.

I’ve done some research into English courtesans at the tail end of the 18th century and wrote a post about the importance to jewelry to them, too. Reynolds’ Portrait of Kitty Fischer as Cleopatra Dissolving the Pearl is a great illustration of that.

Thank you! When you think of the role jewels played in a courtesan’s life, it is interesting to note how important jewels are to many women–they are status symbols, they are security, and they are for beauty. Also, what does the fascination with Elizabeth Taylor’s jewels mean? Was she a bit of a courtesan since the bulk of her collection derived from her lovers and husbands? Is there more power in the ability to purchase one’s own jewels, or to have them showered on you by men?

Hi, I have started following your blog a few days ago as I am now obsessed with the era. I will follow you regularly. Your courtesan photos show interesting variations on the “dog collar” around the neck. I put a link to this blog on mine. Regards from Cape Town. Marie Theron.

Hi Marie! Poke around the site to get your Edwardian fix–I’m sure there are many topics that will interest you. And yes, the dog collar was a very unique piece of jewelry during the Edwardian era. It actually became a fad when Queen Alexandra, when Princess of Wales, began to wear them to hide a scar on her neck (and no doubt, as she aged, to hide its effects!). Thank you for stopping by and for linking to this site.