When Madame Marguerite Steinheil paid an illicit call on President Félix Faure at the Palais de l’Élysée, no one could have predicted a scandal–and a farce–beyond imagination. Had Mme. Steinheil been your average concerned French citizen, the afternoon appointment with the portly statesman would have aroused little attention save a mention of the woman’s attractiveness. But it was not to be, for within moments of Madame Steinheil’s entrance into President Faure’s office, the bell was rung for his servants, who quickly gathered around the dead body of their master and ruler while the fatale Madame Steinheil adjusted her clothing.

The death of President Faure at the, um, hands of Madame Steinheil came at a critical juncture in French history. Faure’s last years were mired in the Dreyfus Affair, anarchists bombings in Paris, the Fashoda Affair, and a Franco-Russian alliance. With this sort of stress, it is no wonder he found comfort in the arms of Marguerite, but she was even more complicated than diplomatic and domestic contretemps–and this was not the end of her scandalous and deadly reputation. Considering the course of Marguerite Steinheil’s life, it seems a bit ironic that she was born in Alsace two years before the Treaty of Frankfurt ripped it and Lorraine from French hands (these two departments were a source of much bitterness between France and Germany from 1871 until the end of WWII). From birth Marguerite, or Meg, as she was known, was headstrong and independent. Her family hoped she would settle down to become a proper French wife and mother when she married the much-older painter Adolphe Steinheil in 1890, but it was not to be. Meg reveled in her new freedom and began a salon in Paris.

From the start, Meg favored politicians and financiers, gathering around her such luminaries as Gounod, Ferdinand de Lesseps, Jules Massenet, François Coppée, Émile Zola, and Pierre Loti, and fancying herself a modern-day Madame de Pompadour in terms of influence. With this goal in mind she was determined to meet President Faure. Opportunity came knocking when her husband, whose talents were small, yet prolific, was given a contract by Faure in 1897. This of course gave the now-smitten President an excuse to pay her frequent visits. Meg was soon installed as Faure’s maitress-en-tete, but she held little real influence or power save what she thought in her head. After Faure’s sensational death, Meg moved on to other wealthy and powerful men, who, per her Memoirs, entrusted her with state secrets. Her most important lover was the powerful industrialist Borderel, whom she met in 1908.

But Meg’s bid for infamy was not over.

In May of that year, Meg’s husband and stepmother were found suffocated in their beds and Meg herself was bound and gagged to her bed. She claimed to have been tied up by four hooded strangers, and the public speculated (with her instigation no doubt) that her family had been murdered in an attempt to search the house for sensitive papers Faure had left in her care. From the start, the police just didn’t find the story believable. However, since they had no evidence with which to charge Meg, the case was dropped. Oddly enough, Meg would not let the case go and her attempt to frame two of her servants caused the police to arrest her for the murders.

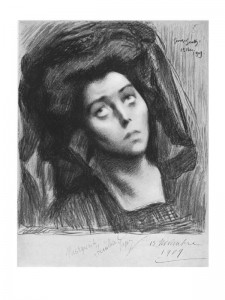

The court case caused a sensation that rippled through Paris. Men thought Marguerite innocent, while the women thought her absolutely guilty. The prosecutors brought forth witnesses from her childhood to the present to recount every sin she’d ever committed, including the names of her numerous admirers. The courtroom was packed on every day of the trial and when Meg took the stand, the obsession with her case reached a fever pitch. Marguerite was a consummate actress, weeping, gnashing her teeth, and wailing about her innocence and her grief over the tragedy. No matter what angle the chief prosecutor came from, she stuck to her story, and after a strange man dressed in a red wig and black cloak made an appearance in court to testify breaking into the Steinheil home, the case was ruined. The jury deliberated for 2 1/2 hours and although the judge called her stories “tissues of lies”, they announced Marguerite’s acquittal on November 14, 1909. She promptly quit France for England, where she “wrote” My Memoirs (1912) and later wed the 6th Baron Abinger. Marguerite was widowed in 1927 and lived in England for the remainder of her life, dying in a Hove nursing home in 1954.

*gasp* I’ve never heard of her but *wow*, I love her! She’s definitely a fascinating woman!

😀 She is definitely fascinating. I’ve enjoyed her story since I read a footnote about her dastardly deeds in a book on Marcel Proust’s Paris.

I’ve always found the story of Marguerite Steinheil fascinating. Do you have any books, besides her autobiography, you can recommend?

Me too! When I find these women I have to laugh and marvel because they were extraordinary at a time when most women were not. But I highly recommend The Hypocrisy of Justice in the Belle Epoque by Benjamin F. Martin. It covers not only Marguerite’s murder case, but the assassination of journalist Gaston Calmette by the French Minister’s wife, and the con woman Thérèse Humbert.