Ten years after Queen Victoria’s Golden Jubilee, the Diamond Jubilee planned to celebrate her sixty years on the throne was to be the celebration of the mighty British Empire. Under the helm of Joseph Chamberlain, Colonial Secretary, self-made Birmingham businessman, and gung-ho imperialist, the empire-wide celebrations were to strengthen the ties between the Queen and her 450 million subjects, restore the slight tarnish to Britain’s name after the embarrassing Jameson Raid, and allay any fears of Britain’s commercial and industrial decline in the face of increased German and American competition. With those goals in mind, the Diamond Jubilee was bold, lavish, and ostentatious in appearance.

By the late 1890s, new technology (i.e. the cinema), coupled with the birth of the tabloid press and increase in literacy (since the year 1897 marked a full generation after the passing of the Elementary Education Act of 1870), widened the scope of promotion and broadcasting of the Diamond Jubilee and whipped the excitement to a fever-pitch.

More than one million people were expected to descend upon London during the two weeks of festivities, and those with houses along the procession route made serious profits on visitors unable to book a hotel (on a less exciting note, those merely renting houses along the route were induced to leave by landlords to make way for wealthier tenants willing to pay inflated rents for just that year–“Jubilee Evictions”). The metropolis was decorated from West End to East End with “V.R.”, there were “roses, lions, crowns, unicorns, wreaths, banners, and pictures of the Queen at every turn”, and “scaffoldings had been built in front of [houses along the procession route], and sometimes even far above the roofs, so that as many seats as possible might be rented.”

As June 22nd drew near, troops from every British colony could be seen in London and no doubt provided the majority of Britons their first experience with Britons of color. The procession was to follow a route six miles long, starting at Buckingham Palace, where first the Royal Horse Guards, the 1st and 2nd Life Guards, the Scots Greys, the Colonial representative troops (700 in number), and a special escort of Indian officers representative of every principal regiment in India passed through the gates, then the Headquarter Staff of the Army, including the Commander-in-Chief Lord Wolseley and the Duke of Conaught, and finally the Princesses of the Royal Family in carriages and the Princes on horse back–with the Prince of Wales in the place of honor–, before the Queen’s carriage rolled out.

As the Queen passed through the doors of Buckingham Palace at eleven o’clock, she sent to every colony the message: “From my heart I thank you, my beloved people. May God bless you.” The long cavalcade went on slowly to Temple Bar, the old entrance to the city. There the Queen paused, and the thousands in line paused. The Mayor, most imposing in his long velvet cloak, presented her with the sword of London in token of the city’s homage. She touched the sword in acceptance, and the procession moved on.

The second stop was at St. Paul’s. The eight cream-colored horses were reined up before a superb mass of color and glitter, for on the steps of the church were ambassadors, bishops, archbishops, judges, and musicians, flashing with diamonds, gleaming in cloth of gold, gorgeous in the red, blue, and pink hoods of the universities, and all framing in a great square of whiterobed little choir-boys. Prayer was offered, the Te Deum was chanted, ” God Save the Queen” was sung, and thousands of people wiped their eyes as they joined in ” Praise God from whom all blessings flow.” The benediction was pronounced, and the procession turned slowly away. And as the tread of the horses sounded again on the pavement, the Archbishop forgot his magnificent canonicals, he forgot everything except that he was an Englishman and that Victoria was his Queen, and he led the whole ten thousand people in three tremendous cheers for their sovereign.

The procession then made its way to and across London Bridge, through the Borough of Southwark and the Borough Road of Westminster Bridge Road, and then recrossed the Thames by the Westminster Bridge. They passed the Houses of Parliament, the Home Office, Downing Street, and then then old Banqueting Hall, until turning into the Horse Guard’s Parade, and back to Buckingham Palace at 2 PM.

That night everything was illuminated that could be illuminated; and, as in 1887, beacon fires flashed from hill to hill and from headland to headland. The Prince of Wales suggested that the best memorial of the day would be a general subscription to pay the debts of the principal hospitals, and in a great sweep of generosity $3,750,000 was promptly subscribed. The Princess of Wales wrote to the Lord Mayor of London, expressing her interest in the poor of the city, and gifts amounting to $1,500,000 were made at once for their benefit.

The rejoicing went on for a fortnight. There were reviews of soldiers and of battleships, there were concerts, exhibitions, and dinners for the poor. One part of the celebration was the manufacture of a mammoth cake by the same firm that made the coronation cake. This Jubilee cake weighed five hundred pounds, and five hundred more was added to it in frosting and sugar ornaments. Around it was a great wreath of sugar roses. A lofty tower of sugar rose from within the wreath with many monograms, medallions, crowns, lions, unicorns, angels of fame and of glory blowing great sugar trumpets; and at the very top was the angel of Peace with white and shining wings. — from London of To-Day (1897) and In the Days of Queen Victoria (1900)

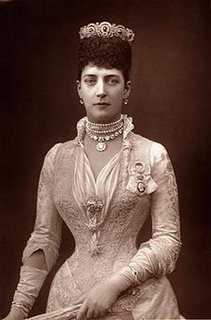

To cap off the Jubilee celebrations was the huge fancy dress ball held on July 2nd by Louise, Duchess of Devonshire at Devonshire House on Piccadilly. According to The Times, “never in our times has so much attention been paid to old family pictures, never have the masterpieces of portraiture in the National Gallery been so carefully studied, while for weeks past the Print-room at the British Museum, commonly given up to quiet students, has been invaded by smart ladies and gentlemen anxious to search the prints and drawings of the 16th, 17th and 18th centuries for something in which they could obey the Duchess’s summons to appear ‘in an allegorical or historical costume dated earlier than 1820’.” Couturiers and hairdressers were booked months in advance to create costumes and hairstyles based on certain pictures and representing certain characters, and even those heavily in debt spent money they did not have in hope of outdoing their friends and acquaintances.

The Times again:

“The innovation of yesterday was the idea of different Courts headed by various well-known ladies and attended by their friends as Princes and courtiers. The Royal party itself fell in very readily with this idea, and attended in historical and mostly Royal costumes of the 16th century. There were four Courts strictly so-called, besides two groups which were separately arranged, but which are only to be called Courts by an extension of the term. The four were the Elizabethan Court, headed by Lady Tweedmouth as Queen Elizabeth with Sir Francis Jeune as Lord Chief Justice, Lord Arran a Cardinal, and Lord Rowton as Archibishop Farrer; the Louis XV and XVI. Court, with Lady Curzon as Queen Marie Leczinska and Lady Warwick as Marie Antoinette; the Court of Maria Theresa with Lady Londonderry as the Empress, Lord Lansdowne as Prince Kaunitz, and Lady Lansdowne as Lady Keith; and the Court of the Empress Catherine II of Russia, its Imperial centre being Lady Raincliffe. Of equal importance with these Courts were the group of Orientals and the Italian procession, the chief members of the former being the hostess herself, the Duchess of Devonshire as Zenobia, Lady de Grey as Lysistrate, and Lady Cynthia Graham as the Queen of Sheba; while the latter, which covered not only the great period of Italian art but the 17th century as well, was made illustrious both by the beauty of the dresses and by the great distinction of many of those who wore them.”

As the festivities wound down and life settled back into its regular patterns, Britons no doubt felt all must be alright in the world, and the fierce gong of imperialism and nationalism, and comfort and familiarity of the long and doughty reign of Queen Victoria, allowed most to paper over the cracks in British society. Yet even before the Queen was to pass out of their lives after sixty-four years on the throne, many realized how drastically the world had changed since an eighteen year old woman promised to “be good” in 1837, and no amount of parties or celebrations could obscure that fact.

Further Reading:

Photographs of the Duchess of Devonshire’s Ball

Article in The Times – July 3, 1897

Twilight of Splendor: The Court of Queen Victoria During Her Diamond Jubilee Year by Greg King

Queen Victoria and Britain’s first Diamond Jubilee – BBC

The last Diamond Jubilee: How Britain was very different but strangely similar in 1897 – The Mirror

Queen Victoria’s Journals

Wearside Echoes: How Sunderland celebrated Queen Victoria’s Diamond Jubilee

Queen Victoria’s Diamond Jubilee Scrapbook

I was reading an article a month or so back, that those “Jubilee Evictions” are still going strong — only now with the Olympics in London.

@Gibson Girl: How sad!

450 million subjects? Good grief… No wonder the celebrations were so impressive. I used the Diamond Jubilee photos in the lecture, this afternoon 🙂

Isn’t blogging brilliant?

@Hels: Yes! And it was probably the first time Britons were in close contact with fellow subjects from Africa, India, and Asia.