Less opulent than Buckingham Palace, less iconic than Windsor Castle, and definitely less bombastic than Balmoral, the royal residence of Sandringham House in Norfolk was built for privacy and simplicity. Here, on his own country estate King Edward VII could relax from the formalities of his rank, he could romp with his family and close friends, and he had full control over the workings of the household. Though as King, he did not have as many opportunities to travel to Sandringham as he had when he was merely the Prince of Wales, Edward more than made up for his absence during Christmastime.

At Sandringham one could expect the holiday to be celebrated in a good old-fashioned style, “uniting all the mighty feasting, the sports and merriment, the decorative use of flowers and evergreens which trace back through centuries of our history past the Christian story into Druidical mists, to the pretty customs of the Christmas tree, with its adornment of tinsel, flags, crackers, and flaring tapers, and the midnight invocation of Santa Claus, which were brought over from Germany by the Prince Consort.” The guests consisted only of members of the Royal Family, who purchased their presents in advance in London, or selected items sent to Sandringham by the most fashionable tradesmen and department stores. In the ballroom was the great Christmas tree upon which hung the presents for King Edward’s grandchildren and every other member of the household, down to the humblest governess.

On Christmas Eve, the King and Queen distributed joints of beef and other substantial foodstuffs to the labourers, workmen, and cottagers on the Sandringham Estate. In addition, gifts such as warm garments, toys, and other useful items were sent around to the cottages. On Christmas morning, the adults were wakened by the State Piper, who played his bagpipe as he walked around the house. Of course the children were awake and full of glee, and there was much excitement when the adults went down for breakfast in the Dining Saloon. The presents were passed around as everyone ate–or tried to eat–breakfast, and to that purchased by the family members for one another at Sandringham were the piles and piles of gifts posted or sent by rail from the many relatives abroad.

On Christmas Eve, the King and Queen distributed joints of beef and other substantial foodstuffs to the labourers, workmen, and cottagers on the Sandringham Estate. In addition, gifts such as warm garments, toys, and other useful items were sent around to the cottages. On Christmas morning, the adults were wakened by the State Piper, who played his bagpipe as he walked around the house. Of course the children were awake and full of glee, and there was much excitement when the adults went down for breakfast in the Dining Saloon. The presents were passed around as everyone ate–or tried to eat–breakfast, and to that purchased by the family members for one another at Sandringham were the piles and piles of gifts posted or sent by rail from the many relatives abroad.

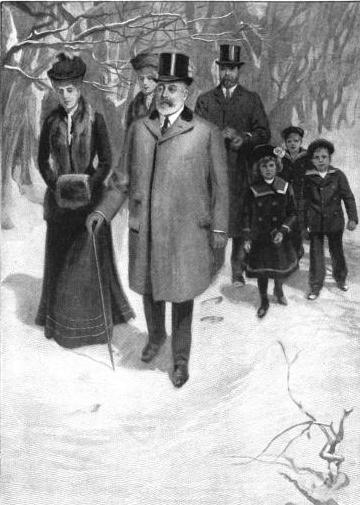

After this, everyone tramped from room to room, examining the decorations of holly and mistletoe put up by Queen Alexandra, her daughters, and members of the household, and then went upstairs to dress for church. The King and Queen led the way on foot across the park to the church of St. Mary Magdalene, which was also decorated by Alexandra. The Royal Family sat within the chancel, and the rest of the church was filled with “the suite and servants, some of the children of the Royal Schools, and a few visitors”. The sermon, in accordance with the King’s wishes, never exceeded twenty minutes, and once the service ended, the congregation rose and remained standing until the whole of the Royal Family had departed.

The children were left to eat luncheon (a concession to the holiday was the flambeed pudding!), while the adults spent the afternoon out of doors, motoring, driving, ice-skating, walking, riding, and visiting the kennels. After tea, the children were herded downstairs and into the saloon, where their presents hung from a blazing Christmas tree. Everyone spent a few hours in games with the junior members of the Royal Family until they were tired out and sent to bed. Later that evening, everyone who pulled a ticket were summoned to the ballroom, where a table circled the Christmas tree was laden with presents. Courtiers, tenants, and servants received gifts from the King and Queen, usually comprising of “handsomely-bound books, articles of jewelry, etc from the King, and books, art pottery, art needlework, wood carving and silk dresses from the Queen–the latter being chosen as presents to the upper servants.” Edward delighted in this activity, and Alexandra threw herself into the spirit of the day, flinging packets of crackers and sweets to queue of people.

The children were left to eat luncheon (a concession to the holiday was the flambeed pudding!), while the adults spent the afternoon out of doors, motoring, driving, ice-skating, walking, riding, and visiting the kennels. After tea, the children were herded downstairs and into the saloon, where their presents hung from a blazing Christmas tree. Everyone spent a few hours in games with the junior members of the Royal Family until they were tired out and sent to bed. Later that evening, everyone who pulled a ticket were summoned to the ballroom, where a table circled the Christmas tree was laden with presents. Courtiers, tenants, and servants received gifts from the King and Queen, usually comprising of “handsomely-bound books, articles of jewelry, etc from the King, and books, art pottery, art needlework, wood carving and silk dresses from the Queen–the latter being chosen as presents to the upper servants.” Edward delighted in this activity, and Alexandra threw herself into the spirit of the day, flinging packets of crackers and sweets to queue of people.

The crowning ceremony of the day was Christmas dinner. At 8:45 Sandringham Time, the guests and all members of the Household commanded to dine with their Majesties assembled in a large drawing room about fifteen minutes before the appointed time to settle who was to take whom in to dinner. Three minutes before the clock chimed, everyone passed through the drawing room two by two, in order of precedence, and took their seats at the series of oval tables laid in the Grand Dining Saloon. Servants clad in splendid liveries of scarlet coats and waistcoats trimmed with gold braid, wearing gold stocks in place of collars, white satin breeches, stockings, and shoes stood at attention, and there were special footmen immediately behind the chairs of the King and Queen, to whom the regular footmen brought dishes from which these special footmen served Their Majesties. The tables were laden with gold and silver plate, rare flowers, and a pure white china service decorated with the Royal Arms and the Garter. The menu comprised of barons of beef, cygnets, turkeys, plum puddings, mince pies, etc, of which everyone had to consume within the hour allotted to dinner.

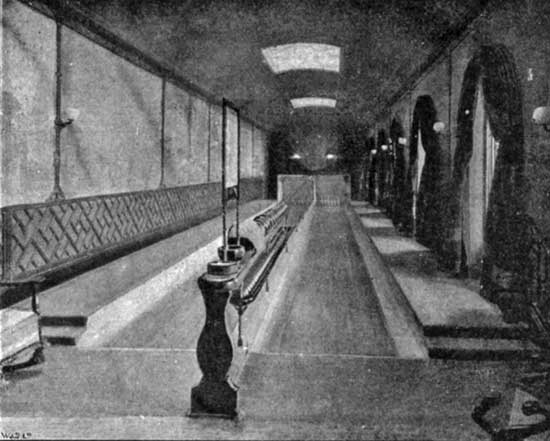

At the end of dinner, the Queen signaled the most exalted guest and everyone rose as the ladies retired to the drawing rooms. The King and the gentlemen followed suit in twenty minutes (Edward, when Prince of Wales, found dawdling over port and cigars with men tiresome, and shortened that postprandial interlude drastically), after which there was either a dance or a Command Performance of that season’s most fashionable play or musical comedy, or perhaps simple pleasures such as bridge, parlor games, music, or a turn in the American-style bowling alley. This intimate Christmas celebration lasted into the wee hours of the night, and the following day was when the servants’ had their Christmas dinner, where certain favored guests were issued invitations, and they and the King and Queen joined the merriment belowstairs.

At the end of dinner, the Queen signaled the most exalted guest and everyone rose as the ladies retired to the drawing rooms. The King and the gentlemen followed suit in twenty minutes (Edward, when Prince of Wales, found dawdling over port and cigars with men tiresome, and shortened that postprandial interlude drastically), after which there was either a dance or a Command Performance of that season’s most fashionable play or musical comedy, or perhaps simple pleasures such as bridge, parlor games, music, or a turn in the American-style bowling alley. This intimate Christmas celebration lasted into the wee hours of the night, and the following day was when the servants’ had their Christmas dinner, where certain favored guests were issued invitations, and they and the King and Queen joined the merriment belowstairs.

The next few days after this were usually devoted to a shoot. Four to six crack shots were invited to Sandringham to enjoy what was considered the best shooting in England. All farm machinery was at a standstill so as not to disturb the birds, and farmhands with blue and red flags, attired in smocks and with red bands around their hats, were taken to their places by the gamekeepers. Game carts were sent to the places where the firing was likely to the “hottest,” and when all was ready, the vehicles carrying the King and his guests rumbled across the estate. The guns were out all morning, booming and crackling across the sky. At one pm, the ladies were expected to grace the luncheon tent with their presence, where everyone dined on plain and simple dishes like Irish stew, roast beef and Yorkshire pudding, or boiled beef and batter pudding. By the close of December, the celebrations at Sandringham had ended; however, King Edward and Queen Alexandra always extended their holidays with their annual New Year’s house party hosted by the Duke and Duchess of Devonshire at Chatsworth, where they enjoyed the same degree of intimacy and privacy as at Sandringham.

Sources

“Christmas with the King and Queen” by Mary Spencer Warren, The London Magazine, 1904

“How They Spend Christmas at Sandringham” by J.M. Carlisle, The Windsor Magazine, 1899

King Edward As I Knew Him by Charles William Stamper

“Royal Homes of Sport: Sandringham” by Alfred E.T. Watson, The Badminton Magazine of Sports & Pasttimes, 1904

“The World’s Pageant” December 26, 1906, The Bystander

Mmmmm, joints of beef. Yes please. 🙂

What fascinating traditions! My 87yr. old mom says my Grandma (of English & Scottish descent) served Plum Pudding on Christmas Day ! It was doused with brandy & lit before she carried it into the dining “saloon”! I wish I could have seen that!