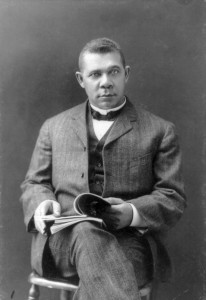

No two men of equal stature could have come from different places than Booker T. Washington and W. E. B. Du Bois. One was born during slavery and worked menial jobs to obtain his education, while the other was raised amongst a relatively well-to-do family with roots in one of New England’s most beautiful towns. Nonetheless, both Washington and Du Bois found their life’s callings in the uplift and advancement of the race, though their differing ideologies regarding the uplift and advancement of African-Americans led to a very bitter rift between their rival factions.

Booker T. Washington made his mark with the infamous “Atlanta Compromise” speech, in which he entreated black Southerners to “cast down their bucket where [they were]” and accommodate white Southerners in hope of obtaining equality through humility and diligence. This ideology of accommodation characterized Washington’s entire career as a “race man,” and laid the foundation for the establishment of Tuskegee Institute, in which he emphasized obtaining a useful trade and equipping students to become teachers of these trades (farming, cookery, etc). He also attracted the attention of America’s leading politicians and philanthropists, who viewed him as the leading voice for African-Americans, and donated enormous sums to his educational and social programs. Because of the swiftness of Washington’s rise to prominence and the influence he had over the powerful in the land, he was called–derisively by his critics and proudly by his supporters–the “Wizard of Tuskegee.” But there was a dark side to his politics: Washington was caught in his own ideology as America reached the nadir of race relations, a time where streets ran red with the blood of victims of brutal and senseless lynchings, and ruthless race riots damaged what little reconciliation had been established between blacks and whites during Reconstruction.

Booker T. Washington made his mark with the infamous “Atlanta Compromise” speech, in which he entreated black Southerners to “cast down their bucket where [they were]” and accommodate white Southerners in hope of obtaining equality through humility and diligence. This ideology of accommodation characterized Washington’s entire career as a “race man,” and laid the foundation for the establishment of Tuskegee Institute, in which he emphasized obtaining a useful trade and equipping students to become teachers of these trades (farming, cookery, etc). He also attracted the attention of America’s leading politicians and philanthropists, who viewed him as the leading voice for African-Americans, and donated enormous sums to his educational and social programs. Because of the swiftness of Washington’s rise to prominence and the influence he had over the powerful in the land, he was called–derisively by his critics and proudly by his supporters–the “Wizard of Tuskegee.” But there was a dark side to his politics: Washington was caught in his own ideology as America reached the nadir of race relations, a time where streets ran red with the blood of victims of brutal and senseless lynchings, and ruthless race riots damaged what little reconciliation had been established between blacks and whites during Reconstruction.

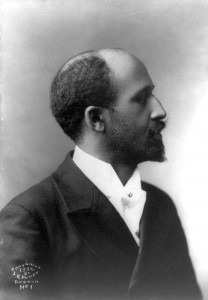

It was during this time that W. E. B. Du Bois launched his attack on Washington’s platform and established himself as a militant and passionate proponent of integration. Du Bois was gifted and relatively privileged from birth, and his early scholastic achievements led him to believe that reason and education were key to overcoming racism. His viewpoint was solidified by his well-rounded education: he attended Fisk University, a top historically black college, obtained his bachelor’s degree from Harvard University, and studied in Berlin. From this extensive scholastic career, Du Bois dedicated himself to the painstaking task of putting the black experience into words. His most lasting and lauded achievements were the publication of his Ph.D dissertation, The Suppression of the African Slave Trade to the United States of America: 1638–1870 (1896), The Philadelphia Negro (1899), and The Souls of Black Folk (1903), the last of which imprinted the phrase “double consciousness” forever into vocabulary of the black intelligentsia.

It was during this time that W. E. B. Du Bois launched his attack on Washington’s platform and established himself as a militant and passionate proponent of integration. Du Bois was gifted and relatively privileged from birth, and his early scholastic achievements led him to believe that reason and education were key to overcoming racism. His viewpoint was solidified by his well-rounded education: he attended Fisk University, a top historically black college, obtained his bachelor’s degree from Harvard University, and studied in Berlin. From this extensive scholastic career, Du Bois dedicated himself to the painstaking task of putting the black experience into words. His most lasting and lauded achievements were the publication of his Ph.D dissertation, The Suppression of the African Slave Trade to the United States of America: 1638–1870 (1896), The Philadelphia Negro (1899), and The Souls of Black Folk (1903), the last of which imprinted the phrase “double consciousness” forever into vocabulary of the black intelligentsia.

By the 1900s, Washington and Du Bois placed themselves on opposite ends of the anti-racism spectrum. As a result, much of their similarities were obscured, and posterity has passed down the belief that Booker T. Washington was passive and desired blacks to remain content as maids and Pullman porters, and that W. E. B. Du Bois desired only for the uplift of light-skinned, college-educated blacks over their darker, less-educated brethren. In both cases, I feel the scope of their writings demanded the inclusion of African-American narratives into the greater American narrative, while acknowledging the multiple threads from which the African-American experience derived.

Further Reading:

Up From Slavery by Booker T. Washington

The Negro Problem, by Booker T. Washington,W. E. B. Du Bois, et al

The Souls of Black Folk by W. E. B. Du Bois

Tuskegee & Its People: Their Ideals and Achievements ed by Booker T. Washington

Of the Training of Black Men by W. E. B. Du Bois

I would love to see a romance set during this time period!