While watching the second episode of Dr. Pamela Cox’s BBC documentary, Servants: The True Story of Life Below Stairs, I was struck by yet another instance of similarity between today and the Edwardian era.

I blogged a bit about Lloyd George and his controversial “People’s Budget“, and the push for national insurance was a part of the Liberal Party (and Lloyd George)’s social reforms of the 1910s.

George Dangerfield’s The Strange Death of Liberal England covers this particular point of the Liberal Party’s history, and in a nutshell, these outrageous reforms–to the establishment at least–inadvertently caused the gradual erosion of their elector base in favor of the Labour Party.

The result of this hard move to the Left was disastrous on Society. After the particularly humiliating struggle between the House of Commons and the House of Lords in 1910 (the Lords were virtually stripped of their power the following year), many aristocrats found social bipartisanship quite difficult (I believe Winston Churchill was considered a traitor to his class).

But I digress. Dr. Cox’s focus is, as seen in the title, on the history of the servant class. The changes created by Chancellor of the Exchequer David Lloyd George’s National Insurance Act had enormous ramifications. By the mid-Edwardian era, the working classes had mobilized: trades unions, Labour Party candidates, societies, etc.

In short, the legislature of the Victorians, which fought for mandatory education for the poor and working class, created a politically mobile underclass who now demanded better wages and conditions, and a greater say in Britain’s political voice. No longer could both major parties ignore or appease the working class and the poor, and the gradual enfranchisement of more and more men meant their needs and desires had to be met or they would take their votes elsewhere (which they did–the aforementioned Labour Party).

The National Insurance Act, gave “the British working classes the first contributory system of insurance against illness and unemployment.” All workers between the age of sixteen and seventy had to join the health scheme, where each worker put in four pence a week, their employer three pence, and the government two pence.

Not only was sick leave now assured (during which one would be paid “10 shillings a week for the first 13 weeks and 5 shillings a week for the next 13 weeks”), but free medical care and unemployment benefits. Unemployment worked rather the same as insurance: “The worker gave 2.5 pence/week when employed, the employer 2.5 pence, and the taxpayer 3 pence. After one week of unemployment, the worker would be eligible of receiving 7 shillings/week for up to 15 weeks in a year.” Two years after the act was passed, “2.3 million were insured under the scheme for unemployment benefit and almost 15 million insured for sickness benefit.”

In 1912, an American magazine discussed the act:

The British National Insurance Act, which provides for sick benefits, medical attendance, hospital treatment and relief for consumptives in sanitariums, went into effect last Monday. It covers all persons engaged in manual labor between the ages of 16 and 70, and all employes, with certain exceptions, earning less than $800 a year. Among those exempt are employes of the government, railroad employes and school teachers, who are entitled to superannuation, municipal employes and certain persons employed casually.

The premium rate for male employes is 14 cents a week, which must be paid by the employer. He is, however, allowed to deduct eight cents of the amount from the workman’s wages. The benefits are a sickness benefit of $2.40 per week for 26 weeks beginning on the fourth day of sickness; a disablement benefit of $1.20 a week afterward, if the employe is still incapable of work; medical treatment or, in lieu, monetary compensation and sanitarium treatment for consumptives. For working women the rate is 12 cents per week, the employer being allowed to deduct 6 cents from the wages, and the sickness benefit is $1.80 per week and disability benefit $1.40 per week. A maternity benefit of $7.20 is also paid unless the husband is insured. The government contributes to the fund 4 cents per employe per week.

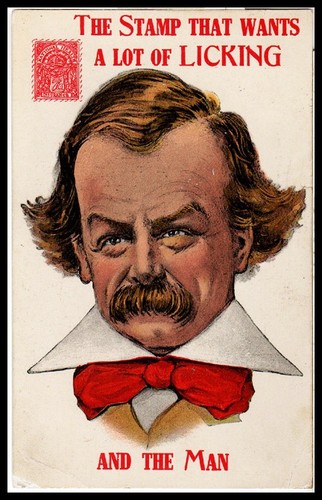

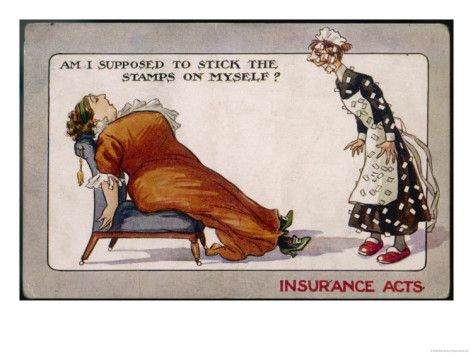

For domestic servants the employer is required to pay 6 cents per week, that is to say, the employer must keep a book in which he must paste stamps to that amount every week, on penalty of $50 for each two cent stamp missing. Employers object to this insurance of domestic servants that they will practically pay the insurance under the “stamp licking act.” The stamps are special health insurance stamps. Every employe must have a card to which the necessary stamps are to be affixed. Such are the main provisions of the law except that to receive its full benefits employes must insure in some approved friendly society.

The act is already causing trouble. Certain classes of casual employes come under its provisions. In such cases the first employer affixes the stamps, and this has led in the case of dock laborers to the establishment of a clearing house for employers who thus pro rate among themselves the cost of the insurance. The laborers object to register under the clearing house plan, and this week 12,000 went on strike in Liverpool and Birkenhead rather than register. The act is not popular, especially as it is believed to be only a part of a program Lloyd-George, the chancellor of the exchequer, has mapped out.

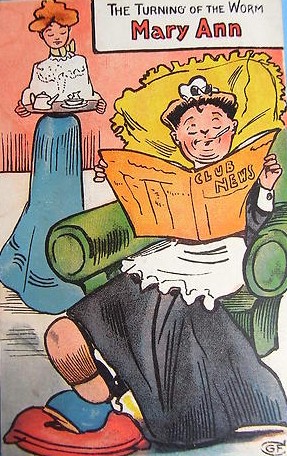

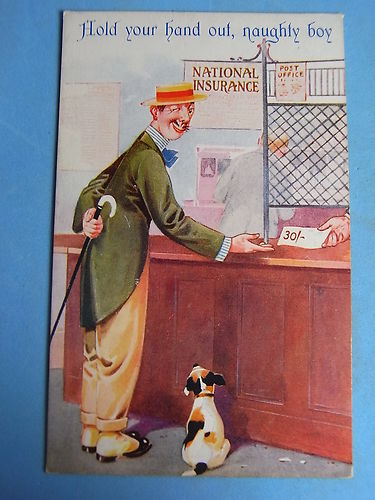

It was unsurprising that the servant-employing class was not happy with this act, and Dr. Cox showed a number of political cartoons and postcards mocking the potential fall-out of the national insurance, ranging from scheming men gaming the system, to mistresses now being obliged to wait upon their own servants when ill.

So as you can see, this act created a complete social upheaval for the Edwardians that occurred well before WWI.

Resources:

1911 National Insurance Act

National Insurance Act 1911

The People’s Insurance by David Lloyd George

Timeline – Trades Unions Congress History Online

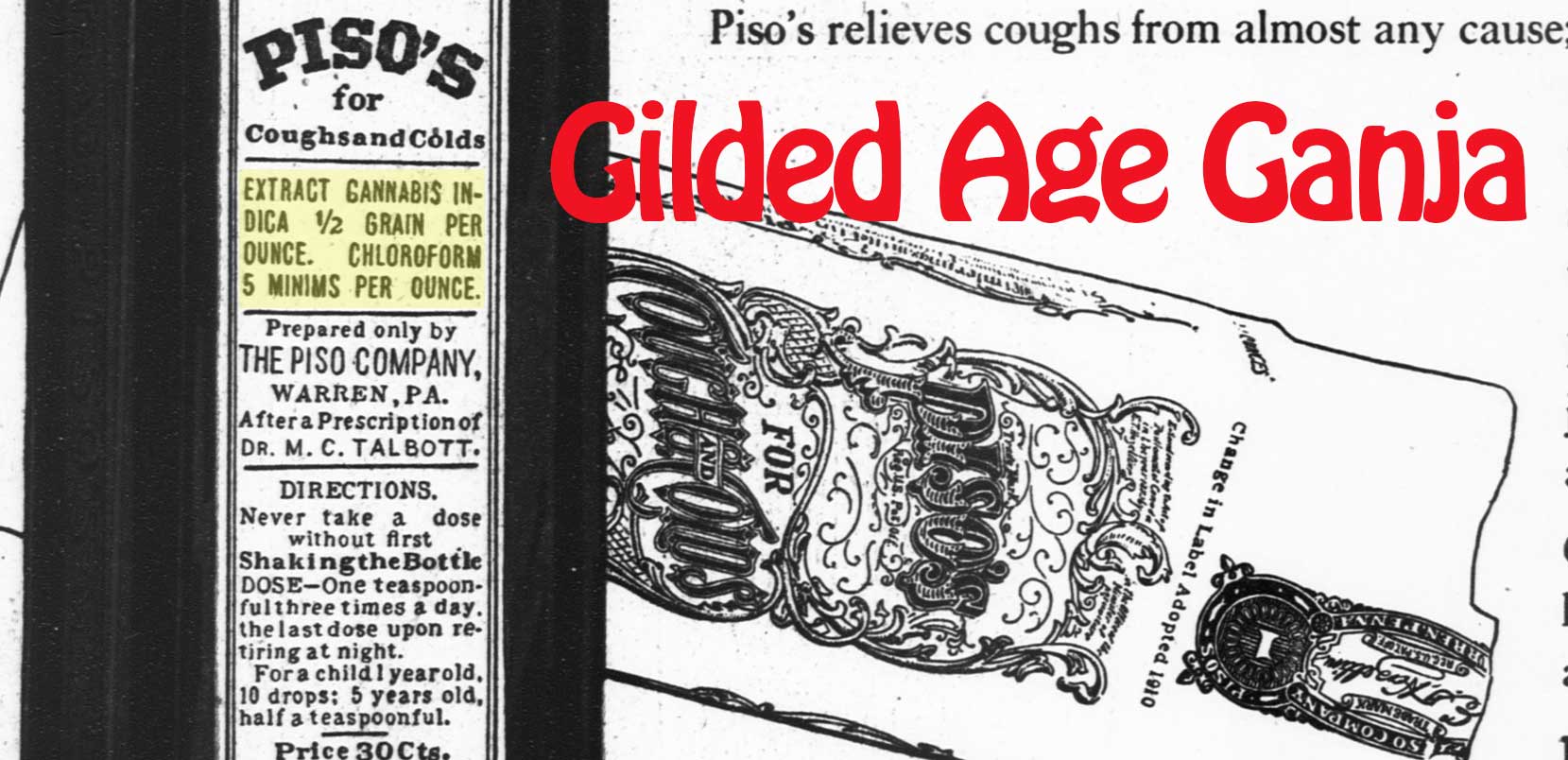

Great images!

The Act was mentioned in the TV series “Parade’s End”–but not in the novels. Tom Stoppard’s script has been published; in the introduction, he mentions his main source for “background”–Juliet Nicolson’s “The Perfect Summer: England 1911, Just Before the Storm.”

The book was published in 2006–you may have mentioned it here. The “Parade’s End” series used many ideas & details from the book, which would be interesting to anybody who studies that era. Along with all the usual High Class Hijinx, Nicolson tells us about Labor unrest–which was certainly warranted! And about the National Insurance Act. And we learn of the early Bloomsbury Group; the author is the granddaughter of Vita Sackville-West & Harold Nicolson.

The summer was unusually warm, which was pleasurable for a while–until records were broken, people died & food became more expensive. Then strikes broke out.

This was the summer King George was crowned; change was in the air, even with the War a few years in the future. You are right–the Edwardian Age was not as placid & unruffled as some think now. Even if the more thoughtless Quality were more upset about those silly hobble skirts & the barbaric Russian Ballet….