Here’s a brief breakdown of the major political parties in Edwardian Britain:

Conservative Party

Tracing its origins to a faction, rooted in the 18th century Whig Party, that coalesced around William Pitt the Younger, it was originally known as “Independent Whigs”, “Friends of Mr. Pitt”, or “Pittites”, but after Pitt’s death the term “Tory” came into use. George Canning first used the term ‘Conservative’ in the 1820s and it was suggested as a title for the party by John Wilson Croker in the 1830s, but it was Sir Robert Peel who adopted the name and is credited with founding the party. After the expansion of the franchise, the party widened its appeal under the aegis of Lord Derby and Benjamin Disraeli, who supported the Reform Act of 1867, which enfranchised working class men. In 1886, the Conservative Party formed an alliance with Lord Hartington (8th Duke of Devonshire) and Sir Joseph Chamberlain’s Liberal Unionist Party, which was comprised of the Liberals who opposed their party’s support for Irish Home Rule and the combined party held office for all but three of the following twenty years. The Conservatives suffered a large defeat when the party split over the issue of free trade in 1906, and in 1912, the two parties amalgamated into the Unionist party.

Leaders between 1880-1914: Benjamin Disraeli, Marquess of Salisbury, Lord Hartington, Lord Randolph Churchill, Arthur Balfour, Sir Stafford Northcote, Sir Michael Hicks Beach.

Liberal Party

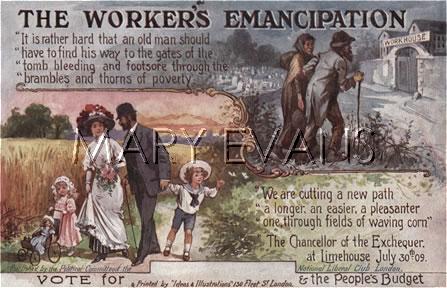

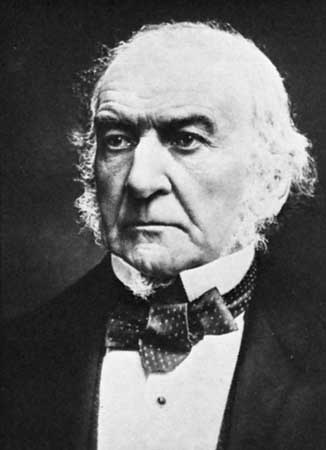

The Liberal Party grew out of the Whigs, which had its origins as an aristocratic faction in the reign of Charles II. The Whigs were in favor of reducing the power of the Crown and increasing the power of the Parliament. As early as 1839 Russell had adopted the name Liberal Party, but in reality the party was a loose coalition of Whigs in the House of Lords and Radicals in the Commons. The formal foundation of the Liberal party is traditionally traced to 1859 and the formation of Palmerston’s second government, but it was after Palmerston’s death that the Liberal Party reached its zenith. For the next thirty years Gladstone and Liberalism were synonymous. The “Grand Old Man”, as he became known, was Prime Minister four times and the powerful flow of his rhetoric dominated British politics even when he was out of office. The Liberals however, languished during the 1880s and 1890s due to infighting and the coalition of the Conservatives and Liberal Unionists. They rose again after the unpopular Boer War, and were led by Herbert Henry Asquith and David Lloyd George. The Liberals pushed through much legislation in the 1906-1911 period, including the regulation of working hours, national insurance and welfare. It was at this time that a political battle over the so-called People’s Budget resulted in the passage of an act ending the power of the House of Lords to block legislation. World War One splintered the group, and it quickly disintegrated after 1918.

Leaders between 1880-1914: William Gladstone, Sir Henry Campbell-Bannerman, David Lloyd George, Herbert Henry Asquith, Winston Churchill (after famously crossing the floor in 1904)

Liberal Unionists

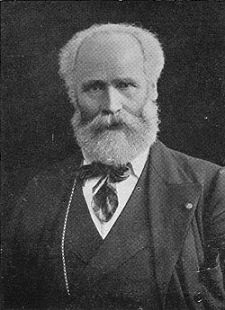

Splitting away from the Liberals in 1886, the party was led by Lord Hartington (later the Duke of Devonshire) and Joseph Chamberlain, and formed a political alliance with the Conservatives in opposition to Irish Home Rule. The two parties formed a coalition government in 1895 but kept separate political funds and their own party organizations until a complete merger was agreed in May 1912. The political impact of the Liberal Unionist breakaway marked the end of the long nineteenth century domination by the Liberal party of the British political scene. From 1830 to 1886 the Liberals (the name the Whigs, Radicals and Peelites accepted as their political label after 1859) had been managed to become almost the party of permanent government with just a couple of Conservative interludes. After 1886 it was the Conservatives who enjoyed this position and they received a huge boost with their alliance with a party of disaffected Liberals.

Leaders between 1880-1914: Marquess of Hartington, Joseph Chamberlain

Irish Parliamentary Party

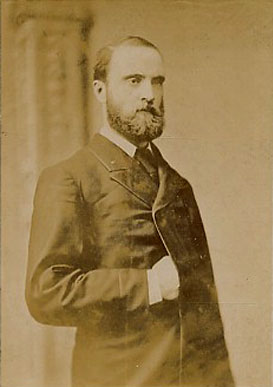

Commonly called the Irish Party or the Home Rule Party, the IPP was formed in 1882 by Charles Stewart Parnell, the leader of the Nationalist Party, replacing the Home Rule League, as official parliamentary party for Irish nationalist Members of Parliament until 1918. The IPP evolved out of the Home Government Association founded by Isaac Butt after he defected from the Irish Conservative Party in 1870, to gain a limited form of freedom from Britain in order to protect and control Irish domestic affairs in the interest of the Protestant landlord class, when William E. Gladstone and his Liberal Party came to power in 1868 under his slogan “Justice for Ireland” and Irish Liberals gained 65 of the 105 Irish seats at Westminster. The party lost its hold when its ardent Catholicism frightened the Protestants, and Butt reorganized the party as the Home Rule League. But no other man is as synonymous with the IPP than Charles Stewart Parnell. Parnell resurrected it in October as the Irish National League (INL). It combined moderate agrarianism, a Home Rule program with electoral functions, was hierarchical and autocratic in structure with Parnell wielding immense authority and direct parliamentary control. Parliamentary constitutionalism was the future path. The informal alliance between the new, tightly disciplined National League and the Catholic Church was one of the main factors for the revitalization of the national Home Rule cause after 1882. Parnell saw that the explicit endorsement of Catholicism was of vital importance to the success of this venture. At the end of 1882 the organization already had 232 branches, in 1885 increased to 592 branches. The INL grew to become a formidable political machine built in the traditional political culture of rural Ireland, for it was an alliance of tenant-farmers, shopkeepers and publicans. The party lost its footing when the scandal of Parnell’s relationship with the very married Katherine O’Shea was revealed, and despite the loyalty of his party and friends, Parnell was disgraced. He married Katherine after her divorce, but died soon after. After his death, the Irish Party put pressure on its traditional ally, the Liberal Party, which culminated in a series of Home Rule bills that tore British opinion apart. The outbreak of WWI distracted everyone from the “Irish Question,” but Ireland took matters into its own hands, resulting in the Easter Rising (1916), the war of independence (1919-1921), civil war (1922-1923) and the eventual partition of Ireland into Northern Ireland (Ulster was anti-Home Rule), and the Republic of Ireland.

Leaders between 1880-1914: Charles Stewart Parnell, John Redmond, Justin McCarthy, John Dillon

Labour Party

The Labour Party’s origins lie in the late 19th century numeric increase of the urban proletariat and the extension of the franchise to working-class males, when it became apparent that there was a need for a political party to represent the interests and needs of those groups. after the extensions of the franchise in 1867 and 1885, the Liberal Party endorsed some trade-union sponsored candidates. In addition, several small socialist groups had formed around this time with the intention of linking the movement to political policies. Among these were the Independent Labour Party, the intellectual and largely middle-class Fabian Society, the Social Democratic Federation and the Scottish Labour Party. In the 1892 General Election, held in July, three working men were elected without support from the liberals, Keir Hardie in South West Ham, John Burns in Battersea, and Havelock Wilson in Middlesbrough who faced Liberal opposition. Concurrently Hardie adopted a confrontational style and increasingly emerged as parliamentary spokesman for independent labour. At the Trade Union Conference meeting in September a meeting of advocates of independent labour organization was called, and chaired by Hardie, an arrangements committee was established and a conference called for the following January. This conference, held in Bradford 14-16 January 1893, was the foundation conference of the Independent Labour Party. The object of the party should be ‘to secure the collective and communal ownership of the means of production, distribution and exchange’. The party’s program called for a range of reforms, with much more stress on the social – an eight hour working day, provision for sick, disabled aged, widows and orphans and free ‘unsectarian’ education ‘right up to the universities’ – than on the political reforms which were standard in Radical organizations. In the 1906 election, the party won 29 seats, during their first meeting after the election, the group’s MPs decided to adopt the name “The Labour Party”. Keir Hardie, who had taken a leading role in getting the party established, was elected as Chairman of the Parliamentary Labour Party. The Fabian Society provided much of the intellectual stimulus for the party.

Leaders between 1880-1914: Keir Hardie, Bruce Glasier, Philip Snowden, Ramsay MacDonald, Frederick William Jowett, William Crawford Anderson

sources: wikipedia