by Victoria Fishburn

Imagine a beautiful woman from Edwardian England who married an Earl, became mistress to the Prince of Wales and astonished Society by standing as a Labour candidate for Parliament. Such a woman was Daisy, Countess of Warwick. Her words, written in two memoirs and countless other books, are still quoted by most historians of the period. In her youth, she was famous for her looks. Cartes-de-visites with her likeness were bought by those who followed the ‘Professional Beauties’, society women whose beauty was admired amongst all classes. Her friend Elinor Glyn referred to her as an ‘It girl’. The fair, curvaceous heiress hit London Society in the 1880s but, although she was painted by Sargent and sculpted by Rodin, her beauty was only part of the reason that she was famous in her lifetime. Even today, her name is widely recognized. This is largely because the life that she led followed so unconventional a path. Despite having good looks, a fortune, a lasting marriage and nine successful years as mistress to the Prince of Wales behind her, she embarked upon a radical life as a social reformer.

My interest in her was sparked by the sheer unlikeliness of her character. She leaves a confusing legacy: an heiress, a Countess and a landowner and yet she signed up to the socialist ideal of land nationalization and tried to give her house away. She had the love of the Prince and yet she pestered him with her ideas for reform. Hugely extravagant, she spent lavishly on entertaining her guests, whilst supporting reforms to help the poor and downtrodden. She stood for a parliamentary seat as a candidate for the Labour party but appeared on political platforms dressed in pearls and furs. Daisy’s life was marked out as unusual from the age of three when she inherited the estates of her grandfather, her father having already died.

The self-confidence and determined independence that characterized her approach to life, started early. She rode dangerous racehorses from her stepfather’s stable, she went to the theatre with Disraeli and, most shockingly, she thwarted the plans of Queen Victoria to marry her to the youngest Prince, her haemophiliac son, Leopold. Brookie was a good catch as heir to the Earl of Warwick but did not have the cachet of a Prince. Young, active and gorgeous she swept all before her as she reveled in her position as Lady Brooke. Having produced a son for her husband, infidelity was accepted in the aristocratic circles in which she moved, as long as affairs were conducted according to that all-important quality of the age: discretion. Daisy threw parties, she bought dresses from Paris by the great French designers, Charles Worth and Doucet, she had lovers and she hunted. But the same impulsiveness that she brought to the hunting field made her indiscreet.

Her reputation was first tarnished by a reckless letter she wrote to her lover, Lord Charles Beresford, berating him for his wife’s pregnancy. The affair foundered at the insult to his wife and recognizing the dire threat of ruin to her reputation, Daisy fled into the arms of the Prince. She entertained Bertie and his friends, first at her own Essex estate and subsequently at Warwick Castle, inherited by her husband Lord Brooke in 1893. Her years as royal mistress should have made her reputation unassailable but even then she was criticized for her indiscreet gossip: a gambling deal involving the Prince of Wales, earned her the nickname, ‘Babbling Brooke’. But both Bertie and Brookie were devoted to her and put up with a great deal. Brookie wrote that he would rather have been married to Daisy ‘with all her peccadilloes’ than to any other woman in the world. They remained married until his death.

Like so many who lavishly entertained their future King, Daisy was extravagant and, what had seemed a great fortune, diminished to the point when she had to sell many of her possessions and property. Her most ignominious episode came about because of debt. After the death of Edward VII, she attempted to raise money by the sale of his love letters to her, offering them, at a price, to George V. The royal advisers were not moved to help her, despite the fact that she had never had the financial benefits and protection given to some of Edward’s other mistresses. She was threatened with an injunction and forced to give the letters to the King. Kept secret at the time, this affair emerged in the 1960s in a book by Theo Lang called ‘My Darling Daisy’ – the affectionate address used by the Prince of Wales in his letters. The name stuck.

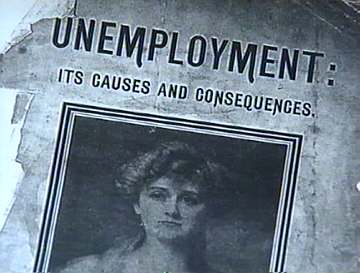

She was given many labels in her life: Professional Beauty, It girl, Babbling Brooke and My Darling Daisy but, before the end of her life, the Countess of Warwick was known by another, and very unlikely, name: the Socialist Countess. At a time when many Edwardians were clinging to the vestiges of a glamorous Society life which was to end with the First World War, Daisy was again stepping out of the mould. Her kind nature and sympathy with those suffering hardship, had inspired her to many philanthropic actions over the years. She had started a home for cripples and a needlework school for rural girls with a shop to sell their work. She funded a secondary school and championed the cause of women’s education by establishing a training college for women. When her days as royal mistress were behind her, she became interested in the rising Socialist movement. Philanthropy turned to Socialism by 1904, when she joined the Social Democratic Foundation. It perplexed her society friends that she should join the highly unfashionable world of trade unionists and socialists. But Daisy had changed. She was no longer interested in Society, her friends now encompassed many fellow Socialists: George Bernard Shaw, H.G.Wells and Gustav Holst were amongst them.

She was given many labels in her life: Professional Beauty, It girl, Babbling Brooke and My Darling Daisy but, before the end of her life, the Countess of Warwick was known by another, and very unlikely, name: the Socialist Countess. At a time when many Edwardians were clinging to the vestiges of a glamorous Society life which was to end with the First World War, Daisy was again stepping out of the mould. Her kind nature and sympathy with those suffering hardship, had inspired her to many philanthropic actions over the years. She had started a home for cripples and a needlework school for rural girls with a shop to sell their work. She funded a secondary school and championed the cause of women’s education by establishing a training college for women. When her days as royal mistress were behind her, she became interested in the rising Socialist movement. Philanthropy turned to Socialism by 1904, when she joined the Social Democratic Foundation. It perplexed her society friends that she should join the highly unfashionable world of trade unionists and socialists. But Daisy had changed. She was no longer interested in Society, her friends now encompassed many fellow Socialists: George Bernard Shaw, H.G.Wells and Gustav Holst were amongst them.

Bravely independent, Daisy increased her literary output in order to make some money. Although never an author of the calibre of Shaw or Wells, it is through her writing that Daisy Warwick maintains her hold on posterity. Between 1898 and 1934, twelve books came out under her name, the first a book on gardens. The subjects were varied: essays on Socialism; a short biography of the leader of the Arts and Crafts Movement, William Morris; a well-respected history of Warwick Castle; a book of essays on the First World War and two substantial books of memoirs. She edited and wrote introductions or essays for a further eight books. Daisy sailed to America in 1912, to give a lecture tour in New York and Washington: the newspapers were full of the outfits she wore and were more interested in society gossip than the socialism she wanted to preach. Back home she contributed articles to London newspapers and the Daily Sketch commissioned her as an advice columnist and editor of their womens’ page. This astonishing literary output kept her name in the public eye.

In 1923, Daisy Warwick stood as a candidate for the Labour Party for the parliamentary seat of Warwick and Leamington. Her opponent was her relation, and later Prime Minister, Anthony Eden. But the overdressed Countess of Warwick, who owed money to many of those who might have supported her, was shunned and, ignominiously, beaten into third place. With this result, she left parliamentary ambitions behind her although she continued to support the Labour Party. In the late 1920s she tried to give her house in Essex away, first to the Labour Party and, when that failed, to the Trade Union Congress. Ironically, it was the fact that she was a Countess and a symbol of privilege that caused the rejection of her offer. Disillusioned with socialism, she retreated back to her home and an old age concerned with the welfare of animals.

Daisy Warwick’s seventy-eight years had been eventful: from her birth as a beautiful and privileged heiress to an old age where looks, money and society friends had all gone. But her name lives on today and this is where her literary output has extended her fame. She is a valuable source for most historians of the late Victorian and Edwardian period. Theo Aronson in The King in Love, Stanley Weintraub in Edward, King in Waiting, Henry Vane in Affair of State, Leo McKinstry in his recent biography of Rosebery, Andrew Roberts in Salisbury: Victorian Titan and Anthony Allfrey in Edward VII and his Jewish Court are just some of the many historians who use Daisy’s insights taken from her memoirs and other writings.

Victoria Fishburn is presently writing a biography on Daisy, Countess of Warwick and can be contacted by email: victoria [at] fishburns [dot] co [dot] uk.

If you're new here, you may want to subscribe to my RSS feed, sign up for my newsletter, or like EP on Facebook. Love what you're reading? Has it helped your school project or book? Consider making a small donation to keep Edwardian Promenade online and a free resource in the years to come!

Thanks for visiting!

What a fascinating life indeed! She sounds like someone I would have liked to know. Are you still writing this biography? I’d be very interested to read it. Also, congrats on being mentioned in The Guardian – that was well-deserved!

Hi Evangeline — I’m an astrologer w/some powerful biographical techniques … I’m doing Daisy’s horoscope and would be honored to work with you. Just got back from a 10 tour of England (on the Trail of Edward deVere) and visited Warwick …