Prior to the Entente Cordiale, which formally ended the traditional hostility between the English and the French, the first move towards ending Britain’s “splendid isolation” was the Anglo-Japanese Alliance of 1902, which was promoted by Viscount Hayashi, the resident minister at the Japanese legation. Eventually, this alliance proved to be another tangle in the multiple tangled alliances that exploded into WWI, but for much of the 1900s and 1910s, the British and the Japanese engaged in a firm (diplomatic) friendship that brought the Japanese residing in England to the fore. The Japan-British Exhibition of 1910 was another attempt to form an even stronger bond with Japan and showcase Japanese culture to Britons. In December 1905, Viscount Hayashi became the first Japanese ambassador to St. James’s when the legation was upgraded to an embassy. The following article was published when he was still resident minister (a post he held from 1900-1905; he was ambassador from 1905-1906).

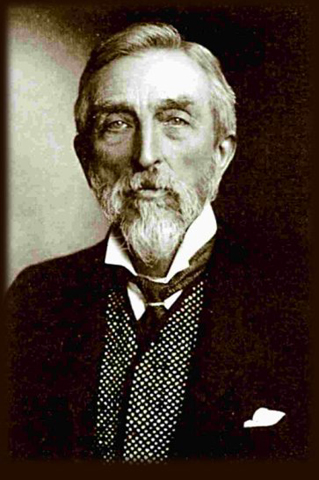

If there is one figure that is in the public eye of London Society at present, it is that of Viscount Hayashi, the Minister of Japan to the Court of St. James. For many months past, ever since the first rumour of impending war between Japan and Russia startled the Western world, the Japanese Legation at No. 4, Grosvenor Gardens, has been thronged by visitors, and all the signs of a Society siege have been here daily visible. But only a few of the many people who have desired an audience of the Viscount have succeeded in obtaining one. Soldiers and sailors, diplomats and politicians have elbowed one another in the waiting-room of the Legation. But no one who does not come on pressing business connected with the war can gain admittance to the sanctuary of the Minister, who has been working day and night deciphering telegrams, writing despatches, and interviewing those who guide the diplomacy of the British Empire.

The furniture of the reception-room consists of a Chesterfield sofa, settees, stand-lamps, and the ordinary ornaments of an English drawing-room. There are not wanting the inevitable photographs in silver frames, and two of these contain portraits of King Edward and Queen Alexandra. Some of the photographs have been taken by Viscount Hayashi himself, for he is an enthusiastic and excellent photographer. In addition to the comfortable modern furniture, there are several kinds of Japanese cabinets filled with carved Nutsukes and objets d’art of all kinds, and fine specimens of Japanese embroidery, carving, and lacquer – work. A striking feature in the room is a wonderfully realistic picture of Fuji, Japan’s famous mountain, which, upon close inspection, is discerned to be not a painting at all, but an exquisite production of needlework on velvet, a masterpiece of industry and artistic feeling.

The Viscount belongs to the Samurai class, with whom we are familiar in the play of The Darling of the Gods at His Majesty’s Theatre. The Samurai were the old feudal nobility, who carried two-handed swords and revolted against the new regime instituted by the present Mikado. When the Civil War broke out the present Japanese Minister was a schoolboy at King’s College, London, and was recalled to fight for the Shogun against the Mikado. The Mikado, being a wise man, made friends with those of his subjects who had taken up arms against him when the Civil War came to an end. And the Viscount, now a young man, entered the diplomatic service, and shortly afterwards was appointed to the Governorship of Kobe, and from that day his rise was rapid.

The Viscount’s favourite recreation, after official day’s work is over, is to stroll through Kensington Gardens, where he usually chooses the less-frequented paths, and to sit for an hour or two under the trees. A keen student, he is never so happy as when he has mastered the contents of some new work, and it is probably due to his omnivorous reading that he has acquired such a wide knowledge of men and things—a quality which has had a notable influence on the success of his career.

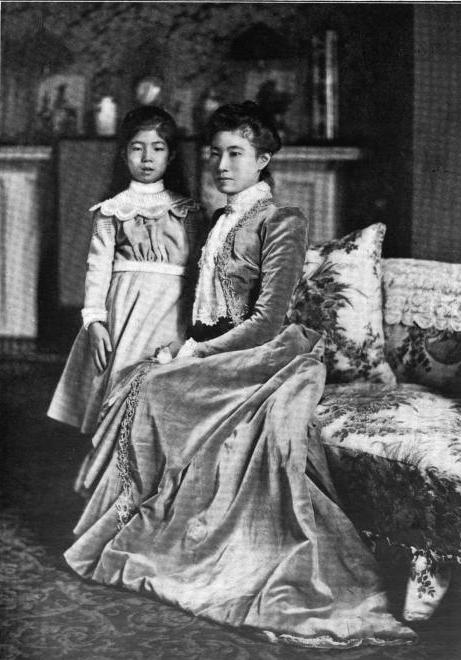

In spite, however, of their devotion to English customs, both the Viscount and Viscountess have a Japanese corner in their lives. One evening in the week the Minister entertains his staff and a few Japanese friends to a genuine Japanese dinner, cooked and served as it would be in the land of the chrysanthemum. To this native banquet no English guests are ever invited. Viscountess Hayashi (née Misao Gamo) has her native entertainment, which takes the form of a tea-party given at stated intervals to the limited circle of Japanese ladies living in London. Indian tea, taken in the barbarous fashion, as they consider it, with milk and sugar, is tabooed, and real Japanese tea, in tiny porcelain cups, pale and fragrant, and without milk or sugar, is served to the guests, supplemented by dainty Japanese sweetmeats and dishes. To this party come the wives of the members of the Legation and their daughters and one or two others, but there are rarely more than a dozen Japanese ladies living in London—so that her ladyship’s native entertainment can only be done on a small scale; yet it is much appreciated, all the same.

Like most Japanese ladies of the upper class, Viscountess Hayashi is a most expert needlewoman, and can show some most beautiful specimens of her handiwork to anyone interested in the fascinating art. She finds English difficult to speak, but converses fluently in French, which is, of course, sufficient to carry her through the social campaign of any European capital, allied as her linguistic talent is to a charming manner and a natural gift for entertaining her friends. She is a typical Japanese mother, very kind but rather strict. Her son is now twenty-five years old, and has spent most of his life in England. At present he is studying electricity at University College. The Viscountess is not only a great reader, but also a close student of current events.

Viscount Hayashi and his accomplished wife, who is, by the way, a member of one of the most aristocratic families in Japan, were often to be met in great London houses, and frequently gave dinner parties. They are both fond of the theatre, and were much interested in Mr. Beerbohm Tree’s Japanese play, The Darling of the Gods. The Viscount is also a most skilful draughtsman and artist, and, among his other accomplishments, possesses more than an amateur’s knowledge of science and the technicalities of engineering. If it had not been for the war he would doubtless have been a listener at the fiscal debates in the House of Commons, for he is a serious student of political economy, and has translated several important works on this subject into his own tongue.

Under these grey leaden skies, with the ceaseless rain beating against his windowpanes, the Viscount sometimes confesses to a slight feeling of home-sickness. But he cheerfully adds that, in spite of our climate, there is no other city in the world in which he would rather live after Tokio. He likes to talk of Japan as the England of the East, carrying the banner of civilisation hand in hand with the England of the West; and nothing pleases him so much as to know that his English friends regard Japan as “the light of Asia.”

— The Lady’s Realm

This is an excellent feature. I enjoyed it very much.

Thank you!

What a stunningly beautiful woman the Viscountess was. Imagine being an expat in those times – so much more difficult than today.

The full article expressed surprise that the Viscountess was a grandmother! 😉

And I too imagine it was more difficult back then. Today you can easily find expat websites and forums to connect and exchange information.