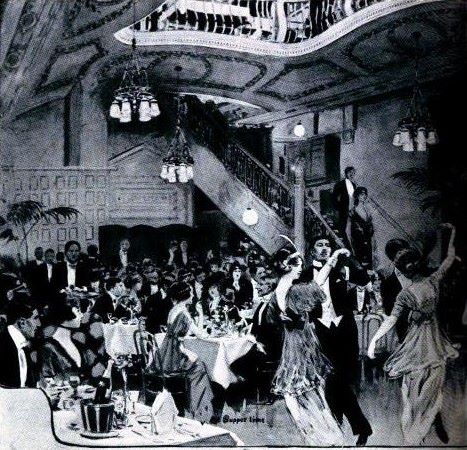

Mr. Selfridge takes license with the life and times of the real Harry Gordon Selfridge, but there actually were nightclubs in Edwardian London! We can thank ragtime and the tango for that, as well as Paris and New York, where the cabaret–dining with a floor show–was popularized by the ultra-fashionable Americans and Europeans who flit across the pre-war world’s glamorous capitals via ocean liners and sleek trains. The only thing that kept London from joining the fun was the London police, who made it difficult for nightclubs to thrive in the English capital.

According to Robert Machray, in his The Night Side of London published in 1902: “The fact is that night clubs have practically become impossible, or almost impossible, in London, thanks to the ceaseless vigilance of the police, whose constant raiding of such dens has made keeping these places a dangerous, and therefore an unprofitable business. From time to time one is started, but it is quickly ‘spotted’ and suppressed. Only a few years ago there were many of them open, furnished with ballrooms, bars, supper-rooms (which had a way of being turned into gambling-hells on the slightest provocation), and a bevy of painted ladies—the whole protected by bullies or ‘chuckers-out.'”

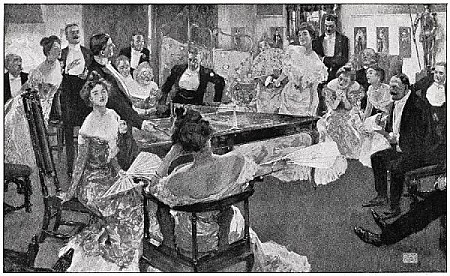

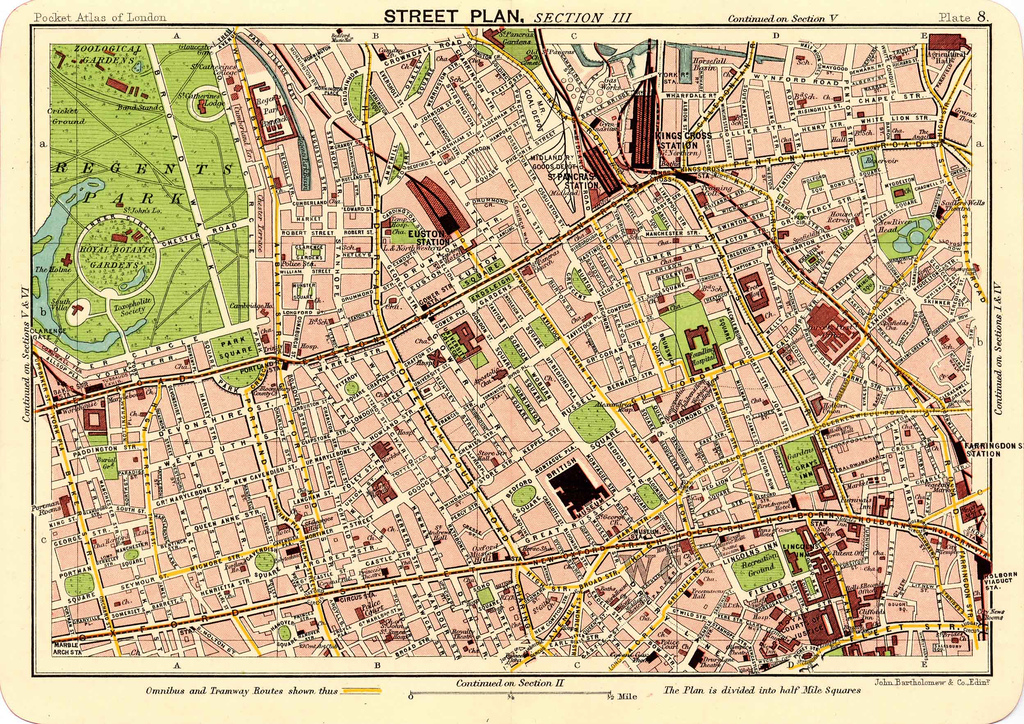

The Cave of the Golden Calf was more avant-garde than previous attempts at owning a club in London, and fit in with the rise of modernism in art, music, literature, and fashion. Founded in 1912 by Frida Uhl Strindberg, an Austrian divorcee (she had been married to Swedish playwright August Strindberg in the 1890s), the purpose of The Cave was “for the promotion of the arts and for the association together of artists and other persons who are interested in literature and the arts.” Madame Strindberg leased a dingy basement below a cloth merchant’s warehouse just off Regent Street, where her artist friends Spencer Gore, Jacob Epstein, Wyndham Lewis, and Eric Gill contributed to the futurist and Russian ballet-inspired art that covered the club’s interiors.

On opening night in June 1912, the basement was packed with journalists, artists, and other curiosity seekers. The Cave’s reputation was immediately sealed as the place to be to rub shoulders with Milanese opera singers, Guards’ officers, and famed artists who sought the latest in drama and entertainment. There one could find leading and soon-to-be leading modernists such as Ford Madox Ford, Katherine Mansfield, and Ezra Pound. Madame Strindberg’s devotion to the avant-garde led her to support–financially and with publicity–many a struggling writer or artist, which eventually led to the financial troubles of herself and of the club.

Nevertheless, from June 1912 to March 1914, The Cave of the Golden Calf helped usher London into place as an influential capital for artistic expression and artistic progressiveness (Roger Fry’s exhibit of Post-Impressionists at the Grafton Galleries in 1911 had shocked the Old Guard at the Royal Academy), as well as Parisien entertainments like dancing the tango or sipping absinthe. Before its doors closed, a number of other nightclubs popped up in London, though these were naturally less avant-garde and more concerned with dancing, dining, and drinking into the wee hours of the night. These nightclubs were particularly seductive to the “Corrupt Coterie,” or the circle of friends made up of the offspring of “The Souls.” Lady Diana Manners risked scandal and censure to sneak out of Mayfair ballrooms to dance and drink with friends at places like The Four Hundred Club or Murray’s, and then tip-toe back just before her mother or brother came to collect her from the ball.

Though The Cave of the Golden Calf went bankrupt months before WWI, it led the way towards to the breaking up of old mores of the long 19th century and pushing society into the 20th century. The club and others like it also set the precedent for the dance- and jazz-mad 1920s, for the war years urged young men and women to drink, dance, and be merry while they still lived.

Further Reading

The Cabaret by Lisa Appignanesi

Oscar Wilde’s Last Stand: Decadence, Conspiracy, and the Most Outrageous Trial of the Century by Philip Hoare

Geomodernisms edited by Laura Doyle

Race and the Modernist Imagination by Urmila Seshagiri

Peace And War: Britain in 1914 by Nigel Jones

Okay between you and Tasha I really have to start watching Mr. Selfridge. This is really interesting about Delphines! Thanks for sharing about it! I really don’t know enough about the Edwardian era.

Yes! Potential recruit into Henri’s Harem. ^^

Feel free to poke around–there are 7 years worth of posts! Plus my book. 🙂