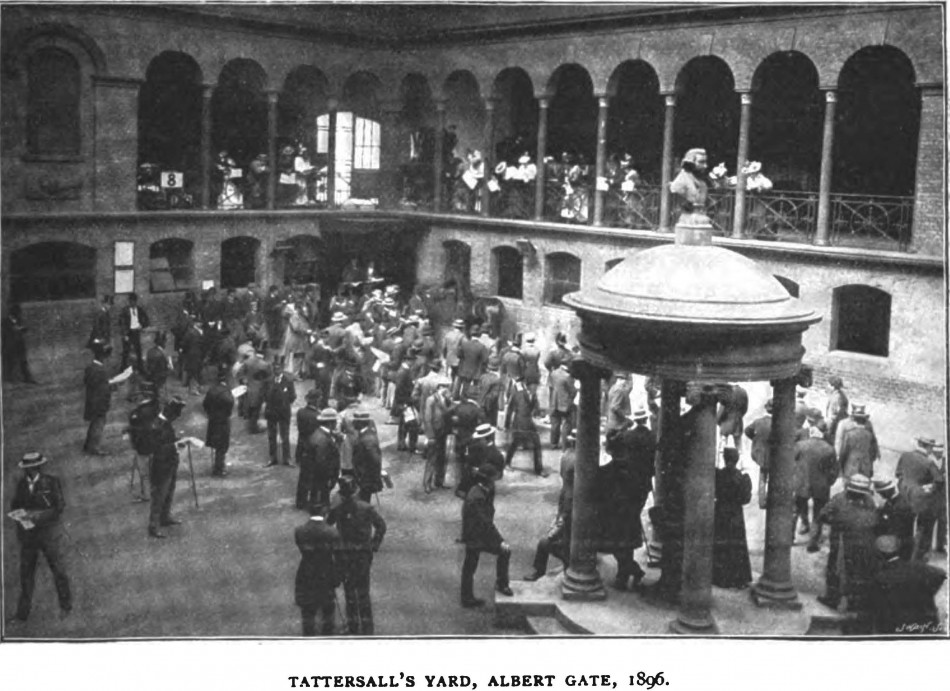

For those of you familiar with Regency romances, Tattersall’s is one of the “hot spots,” so to speak, at which the gentlemen (and some daring ladies) of the ton convened for their horse flesh. Read more about that on Candice Hern’s website. During the Edwardian era, the equine hubbub had dispersed a bit towards other horse repositories such as Aldridge’s in Upper St. Martin’s Lane–which, incidentally, was founded thirteen years before Tattersall’s, in 1753–, the Royal City Horse and Carriage Repository (Barbican) and “Aldersgate in the City, and Ward’s Repository in Edgware Road”. However, despite their presence, the removal of the Jockey Club its own premises, and the move to Albert Gate after the landlord, the Marquis of Westminster, refused to renew the lease on account of the scandalous bets exchanged between bookies and race enthusiasts, Tattersall’s remained and remains the top horse repository in England.

The scene at the Albert Gate establishment on Monday is one worth going far to witness. The dramatis persona is remarkably interesting, and forms a unique opportunity for the study of character. Here may be seen various types of would-be purchasers, from the be-gaitered, straw-chewing, diminutive man with “horse” plainly written all over him from his cap to his shoes, to the stylishly-dressed nobleman in quest of a thousand-guinea pair of carriage horses, the country parson in search of a pony for a governess car, or a smart cavalry man on the look-out for a clever polo pony: men about town, famous jockeys and equally famous trainers, actors and actresses, members of the Stock Exchange and other important city organisations; and not infrequently novelists whose names are household words may be met with in search of local colour for a new novel.

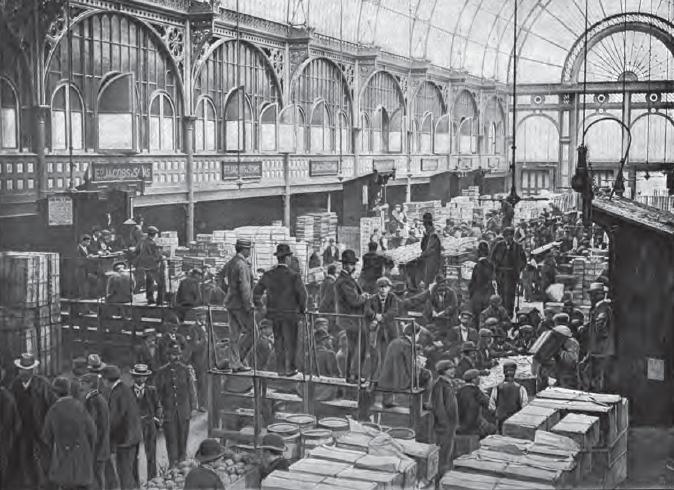

The well-known oblong building with its glass-covered roof witnesses the sale of considerably over ten thousand horses annually. In the surrounding galleries every description of vehicle is standing for sale, governess cars, shooting wagons, landaus, victorias and coaches—a veritable carriage museum. As each potential purchaser of horse-flesh enters the yard, he dives into the office and provides himself with the broad-sheet sale catalogue, which is printed on almost similar lines to that issued by the firm on the occasion of the historic sale by them of the Prince of Wales’ horses at the Hyde Park “Corner” in 1786, a copy of which hangs in a frame in the office. The Prince was, to all intents and purposes, hounded off the turf in connection with the suspicious running of his horse Escape. It may be mentioned that he, when King, actively devoted himself to racing again in 1826.

Punctually at 11.30 the auctioneer ascends the rostrum. “No. 1” is exhibited on a large board by an attendant in the gallery, the animal to be sold is led out from one of the numerous stables, the keen buyers line up, and the horse is galloped up and down through the throng of expert scrutinisers. In a few seconds a horsey-looking would-be buyer steps out of the crowd, takes a lightning glance at the animal’s teeth, runs his hand over his legs and nods to the auctioneer. Bids are fired at the wielder of the hammer like shots from a Maxim gun, but to the casual observer it is a mystery how the auctioneer manages to catch the bids as they take the form of mysterious nods and winks. The quick eyes of the seller, always on the alert, continually roam over the assembled crowd and quickly discern the slightest inclination of the head or covert twitching of an eyelid. Horses find new owners in the course of a few minutes; no time is cut to waste, for usually about two hundred lots require to be disposed of before six o’clock.

The offices of Tattersall’s are exceedingly interesting, as the walls of the rooms and corridors are covered with old prints, engravings, paintings and photographs of famous racehorses, collected by the different generations during the last 137 years. This is undoubtedly the finest collection in the world, and it is uncertain if £100,000 would purchase them. In a conspicuous position over the stairs is a large photograph of the sensational sale of Flying Fox, who fetched the record price of 37,500 guineas. His Majesty the King attended this sale at Kingsclere, and in the photograph the majority of the sporting aristocracy may be recognised.

At frequent periods on the turf, owing to the death of some famous owner, valuable studs of racehorses are in the ordinary course of events brought under the hammer, and to Messrs. Tattersall is deputed the enormous responsibility of disposing of these racers to the best possible advantage. The general public, although such a large percentage of them take a more than passing interest in the sport of kings, have but little idea of the £. s. d. of racing, and when they read in the papers that some famous racehorse has been disposed of at auction by Messrs. Tattersall for ten, twenty, or even thirty thousand guineas, they are naturally astonished.

The inflated prices now paid for celebrated horse-flesh are due to many causes. In years gone by £2,000 was almost an unheard of sum to pay for a horse, even though he had first-class performances to his credit. When the Marquis of Hastings paid £12,000 for Kangaroo, who afterwards, by-the-by, turned out worthless, and ended his days in the shafts of a cab, the entire sporting world was staggered by the enormous amount of the purchase price, and reflections were made as to the sanity of the purchaser.

Nowadays, at Messrs. Tattersall’s celebrated sales at Doncaster in September, thousand-guinea yearlings are almost as plentiful as blackberries, and during the past few years £5,000 has frequently been reached for a blue-blooded baby racer. This is not to be wondered at in view of the fact that stud fees in some instances are as high as four hundred guineas, and the cost of a brood mare may run into many thousands of pounds. The splendid mare, Sceptre, who during the past year accomplished the most extraordinary record of winning the One Thousand Guineas, Two Thousand Guineas, Oaks and St. Leger, in addition to other races—netting for her owner, Mr. R. S. Sievier, the respectable fortune of £25,000——was sold by Messrs. Tattersall to him at the break-up of the late Duke of Westminster’s stud for 10,000 guineas, which was a record price for a yearling.

— The London Magazine, Volume 10 (1903)