The average foreigner who visits London must indeed be of opinion that we take our pleasures sadly. The loneliness which a chance traveller must almost inevitably experience in a great city is proverbial; but if a foreigner be duly armed with letters of introduction to members of fashionable Society he will speedily discover that the pursuit of the business of pleasure is waged more industriously in London than in any other European capital.

He will find every kind of sport ready to his hand. If he is fond of polo, there are clubs where the game is played at Hurlingharn, Ranelagh, and Roehampton. The most beautiful grounds arc those of the Club House —an early Georgian building—at Ranelagh. At Ranelagh, too, there are driving competitions for ladies, horse and dog shows, balloon ascents, meets of stage coaches, and motor-car races. Automobile gymkhanas are arranged, and a band of one of the Guards regiments makes music merry or sentimental the while. Then, if you have no engagement for dinner, or are not obliged to put in an appearance at Covent Garden Opera House, you may dine in the club’s new dining-room, and smoke your cigarette on the lawn afterwards what time the daylight gives place to the mysterious shadows and fragrances of an English twilight.

At Hurlingham the game of croquet flourishes exceedingly. But croquet has become an exact science—almost a duty, instead of a diversion. Yet it is a boon to the occupants of many London houses which have attached to them small gardens. A gardener who will construct a good lawn is never far to seek.

Another form of amusement, this time ostensibly for the benefit of children, is the sailing of model yachts upon the water of the Round Pond in Kensington Gardens. Embryo challengers for the America Cup direct their mimic yachts with considerable skill, although the fathers—many of them sea-dogs who have retired from the Service—stand by to assist in cases of emergency. On a fine Sunday morning, when the clouds fly high and there is a brisk breeze blowing, there will be found a crowd of spectators admiring the expert manner in which the smartly dressed children adjust the rudders and sails of their toys so that when the craft is once adrift it shall eventually find a harbour in some part of the pond.

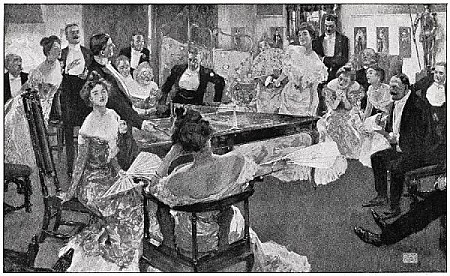

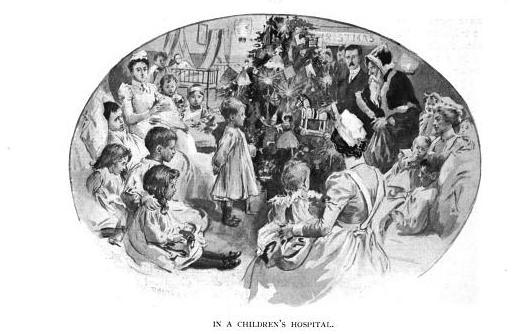

Private theatricals have not at present the vogue which they enjoyed at the end of the nineteenth century. This is because the tendency of the age is all for specialisation, and unless an amateur actor can really act people do not want to be bothered by sitting through a performance which is not efficient. Nevertheless, from time to time entertainments are arranged in private houses by leaders of Society which are often of astonishing excellence. Sometimes a theatrical manager is present, and finds talent of such calibre that he is emboldened to make an offer of a professional engagement. This in many cases has been accepted with successful results. The old-fashioned prejudice against acting or singing as a profession no longer exists. For sweet Charity’s sake tableaux vivants are also arranged, and various funds in connection with the wants of the widows and orphans who have to suffer for the benefit of the Empire have been materially helped by those who have made a fashionable amusement a means of well-doing for others.

During the winter months Prince’s Skating Rink is a favourite rendezvous at tea-time or thereabouts. The artificially manufactured ice on the rink is invariably crowded by skaters; those members who prefer to watch and wait are accommodated with chairs and tables on raised platforms which flank either side of the interior of the building. The cult of the motor-car has had a belated growth in London. The writers who foresaw that, apart from utilitarian reasons, steam or electric traction on the King’s highway was a potential amusement were for a time as voices crying vainly in the wilderness. But London has become converted, and even in Hyde Park the drivers of the automobiles speed merrily on the macadam road which skirts the Row that is sacred to equestrians. Many ladies drive their own machines, whether these latter be of English, French, or American make.

As an amusement “motoring” is incomparable; the mechanism nowadays is so exact that complete control is almost absolutely assured to the driver. But the horse is still with us, despite the prophecies of the quidnuncs, and, although the equipages and horses in Hyde Park cannot compare favourably with those to be seen in the Bois de Boulogne in Paris on a fashionable afternoon, there is a certain quality of solid magnificence which is always impressive.

In the early morning, in Rotten Row on a June day, you may see a Prince of the Royal blood cantering side by side in earnest converse with a Cabinet Minister. Passing them comes a popular actor or a King’s Counsel; a young stockbroker gallops along at full speed, hoping that he shall ride off the effects of a late supper at one of the Society or sporting clubs which he has left but a few hours previously.

In Regent’s Park the game of hockey is very popular. There are several ladies’ clubs, and pupils from fashionable boarding schools and colleges for girls can be seen playing the game with a zest only comparable with that with which a Rugby boy plays football. The sport of archery, which was almost the sole outdoor amusement indulged in by ladies towards the middle of the nineteenth century, is not so popular as it used to be. Nevertheless, the Royal Toxopholite Society holds meetings from time to time in the Royal Botanic Gardens in Regent’s Park, and it is a very picturesque sight on a ladies’ day to watch the fair, up-to-date Amazons drawing the bow, not at a venture, but with nice and exact precision. Some of the shooting is of exceptional merit; the colours of the targets themselves have an Imperial note, which is only fitting when one remembers what a great part the English bow has taken in the formation of our “rough island story.”

Tennis—real tennis, the Royal game, as opposed to lawn tennis and its variants—still has its vogue among those who are able to afford the luxury of membership in the pleasant club, the Queen’s, which is situated in Kensington. Here, watching from the gallery of the building, spectators, guarded from the fearsome effect of blows from the hard ball used by the players by an iron net, may see this glorious game played by enthusiasts in the great spacious court below. At Queen’s, too, members may play rackets—cousin-german of real tennis—-if they be so inclined. Both these games, from the expensive environment which the rules demand, are solely available for the well-to-do strata of Society. Still, they form two facets in the elaborately cut diamond which may be symbolised as London’s fashionable amusements.

Lawn tennis is played in the gardens of houses of the more outlying districts, and wherever space permits. Of indoor games billiards still must be accorded a certain standard of authority. Most large houses contain a billiard room, and nearly all clubs. Fashionable Londoners are whimsical in their adherence to any particular game, and for the moment billiards is somewhat neglected. Nevertheless, every evening you shall see hotly contested games in club or mansion.

In a few houses the billiard table has been sacrificed to a game which bears the sufficiently inane title of “ping-pong.” This is practically lawn tennis played upon a table with a wooden or parchment racket and celluloid balls. It was invented by an Army officer who thought it would be an amusing toy; but the toy soon became a tyrant. “Ping-pong” took the suburbs by storm, and finally even laid successful siege to Belgravia. But the wild enthusiasm with which the game was first greeted cooled after a time, for—as you will notice if you are interested in games—over-proficiency of the few destroys the zeal of the average or amateur many.

Lastly, we come to the all-pervading tyranny of “bridge.” This game, which is a form of whist, has (to use a dear old journalistic phrase) shaken Society to its very foundations. Man, who plays it, cannot resist its fascinations; but Heaven knows the havoc it has wrought among us! This is the average day in the life of a Society woman. At noon a few friends arrive for luncheon—ostensibly. Select parties play bridge until two o’clock, when luncheon is actually served. Bridge again from four to six. Then a drive in the Park, followed by dinner, and—bridge until the small hours of the morning. As a natural corollary—since games of cards are rarely played unless the element of gambling in actual specie enters into the matter—the results of this mania will be apparent to everybody. At clubs the card rooms are filled with quartettes of gamblers; nominal points are exacted by the committees, but this is a matter which is easily evaded by very obvious subterfuge.

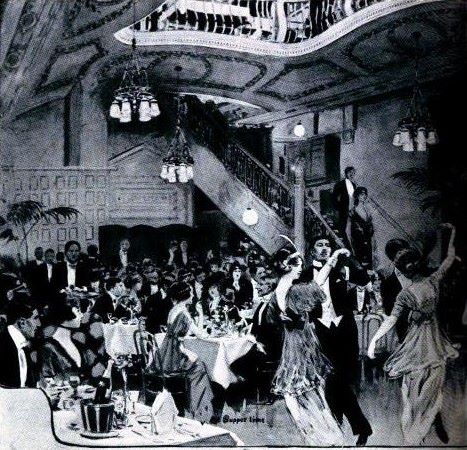

For the rest, fashionable London has concerts, theatres, cricket matches, balls and cotillons, and many other of the raree shows of civilisation. The restless, soul-harassing pursuit of pleasure goes merrily apace— or tragically, which you will. The matter is interesting when one realises how limited fashionable amusements were a hundred years ago. Who shall say what they will be a hundred years hence?

— Living London v3 (1902)

Croquet and bridge. Wild times.

‘The matter is interesting when one realises how limited fashionable

amusements were a hundred years ago. Who shall say what they will be a

hundred years hence?’

The author would probably turn in his grave if he saw went on now!

Thanks for sharing, Evangeline.

Wonderfully informative! Thanks again for an enlightening post.