London in war-time is quite a different London, although at the station there were taxis and small boys to carry our luggage. As usual, the first thing to do was to visit the police, and this time, the Consul, too, for we had to arrange for our passage home and acquire meat tickets as well. As these were for only a week’s ration and we had guests for dinner, they were at once used up, but we didn’t seem to care and got on very well without the meat.

The hotels were gay with people and music as in peace days, but the servants did not answer the bells unless they felt like it. Bread was given at meals, but no sugar was served. Even saccharine could not be procured in its place as in Paris, so we simply didn’t have any until about a week after our arrival sugar suddenly appeared on the breakfast tray. The waiter volunteered the explanation that after a week it was supplied to guests, but I always suspected he gave it or not as his fancy dictated, for he sometimes presented us with matches, but generally did not. Matches were very scarce in London. We were blessed with coal fires and hot baths, however, so what more could we want?

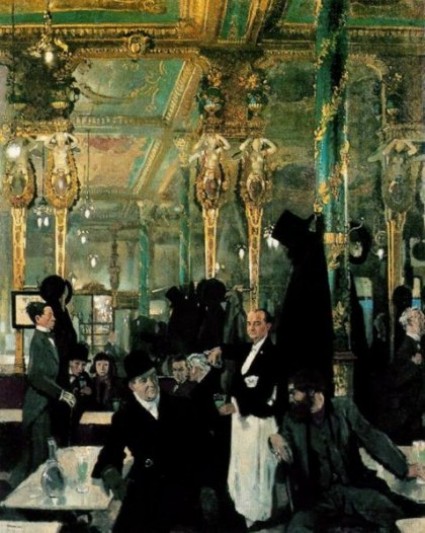

One of our friends, who thought he might allow himself to indulge in some favorite dishes at a London restaurant where he had often eaten, told me his experience: —

“I went to an old restaurant in Regent Street,” he said, “with a mind made up for relaxation and a good dinner, and selected a table. First off the waiter presented me with a miniature dinner card and said that my entire expenditure must limit itself to five shillings, sixpence, including wine. My variety of profanity, however, impressed him as unfamiliar, and he relented enough to suggest that, in case I did not belong to His Majesty’s forces, I might have what I liked; and then expounded the law with all the ifs, buts, and whereas one becomes familiar with in the study of jurisprudence.

“So I ordered a sole and a partridge roasted with a bread sauce, a dish the place has been famous for since first I knew it. In due time, back he came with the usual ‘Very sorry, sir,’ but they had weighed every partridge on the premises, and not one was as small as five and one half ounces. So they could not let me have it. I gave up.

“Every time I ask for a drink some one tells me that the bar will not be open again for two hours, and of course by that time I have forgotten all about it. I asked to have the fire lighted in my room, but it seems that what I had mistaken for coal were merely the crown jewels painted black to give a cheerful, prosperous look to the room, and I barely escaped a charge for treason. So I skim through from one day to another, and will be glad enough to get on the boat Saturday if all goes well.”

~ Zigzagging (1918) by Isabel Anderson

Please keep me updated on new posts.

I think WWI was the beginning of the end of “servant” relationships.

I love that you take excerpts from old books. I almost always go to Google Books or Internet Archive and see if the whole book is available to read. Your posts are tops in my e-mail inbox!