Much as today, the publishing industry of the Edwardian era wrestled with such familiar issues as distribution, declining interest in reading, literary fiction versus “trash” for the masses, competition for bookstores from cheap editions & used book sales, and the eternal assumption of an “us versus them” between aspiring authors and editors/literary agents of major publishing houses. Though things like iPods, television, the internet or video games were not distractions from reading, nonetheless around the turn of the century, the London correspondent of the New York Evening Post reported that the British bookseller was liable to tell a tale of woe: “The trade is not what was once, you know, sir, and what with the war and six-penny reprints, some of us are pretty well at the end of our tether,” and would then “proceed to show you a shelf after shelf of war-books which are not selling, and shelf after shelf of spring which we hoped to get rid of, but which is now so much old stock.”

Much as today, the publishing industry of the Edwardian era wrestled with such familiar issues as distribution, declining interest in reading, literary fiction versus “trash” for the masses, competition for bookstores from cheap editions & used book sales, and the eternal assumption of an “us versus them” between aspiring authors and editors/literary agents of major publishing houses. Though things like iPods, television, the internet or video games were not distractions from reading, nonetheless around the turn of the century, the London correspondent of the New York Evening Post reported that the British bookseller was liable to tell a tale of woe: “The trade is not what was once, you know, sir, and what with the war and six-penny reprints, some of us are pretty well at the end of our tether,” and would then “proceed to show you a shelf after shelf of war-books which are not selling, and shelf after shelf of spring which we hoped to get rid of, but which is now so much old stock.”

At this time the industry was in a state of flux and readership was split amongst such disparate tastes as readers of popular novelists Marie Corelli, Elinor Glyn and Ouida, adventure novelists H. Rider Haggard and Rudyard Kipling, and the Ruritanian genre, and readers of a more serious vein of fiction–G.K. Chesterton, Hilaire Belloc, or the Webbs–though Dickens, Eliot and Thackeray remained perinneal favorites. The quantity of books published during the 1900s advanced considerably, with the number of new publications doubling between 1901 and 1913 from 6,044 in the former year to 12,379 in the latter. This trend lay in the improvement in family incomes and the ever-increasing interest in education, which accelerated with the decline in illiteracy. Aligning with this increase were the sudden growth of public libraries, whose public expenditure jumped from 286,000 pounds in 1896 to 805,000 pounds in 1911. Also, during this time, publishers made an attempt to make the classics more accessible to the reading public, and Collins’ Classics and the Everyman’s Library, each sold at modest prices in relatively durable editions, did much to extend an interest in classic English novelists and essayists.

For the aspiring novelist hoping to break into this seemingly impenetrable market, a score of books nestled on the shelves, some written by popular authors of the day and others by publishers themselves, full of advice on not only how to submit a novel but on the actual publishing process itself. The typical course to publication was detailed as following:

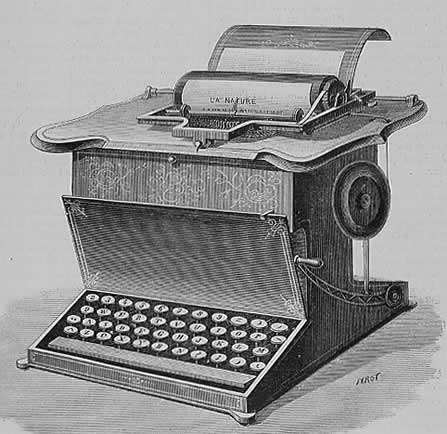

1. First, the aspirant should see that the typewritten copy was accurate, fastened together securely, and most importantly, clean. Their name and address, the title and description of the manuscript, and the length of the manuscript in words, should be prominent on the first page. A letter offering a view to publication and a request for return should the manuscript be rejected accompanied the manuscript in the mail.

2. When the manuscript arrived at the publishers’ offices, a clerk enters the particulars of the book into a ledger and it was shoved aside with other manuscripts to await the casual inspection of a partner or manager. The book is then taken from the pile and handed to a reader. It was their job to sift through the chaff to get to the wheat, and authors were advised to remember that “Publishing firms flourish by making profits; and profits are made out of books that sell; and it is in the business of the reader to recommend not good books merely, but good books that will sell.” Even if the reader enjoyed the book, there was a chance for rejection from the publisher if the lists were full or the reader’s remarks weren’t eye-catching enough. However, should the publisher accept the novel, to the trembling author went a contract.

3. The author was advised that under no circumstances should they bear the whole or part of the expenses of publication–that was to be born entirely by the publisher–nor should he agree to be remunerated on the half-profit system. The newly acquired author would then be remunerated in one of three ways: the publisher buys the entire copyright of the book for a lump sum down, (b) the publisher buys the copyright for a term of years, at the expiry of which it reverts to the author, and (c) the publisher may acquire the right to publish during the whole term of copyright, or for a shorter term, by agreeing to pay the author a royalty on every copy of the book sold (generally 10%, though well-established authors could revieve 25-33%). However, unlike today, this latter system did not guarantee an advance, and first-time authors were advised against insisting on an advance until they made a reputation.

4. The proofs were sent to the author, which were either in long “slips” or in page form, according to arrangement. After the proofs were returned, the next time the author saw their book was when a parcel of six free copies arrived on the day of publication. The author was advised to subscribe to a press-cutting agency for cuttings of reviews. If the first book achieved a sale of a thousand copies it was considered to have done very well, as the average circulation of first books was nearer to five hundred or less. After this first book, the author was further advised to have books published on a moderate, but regular schedule to build their reputation, stating that “even mediocre talent, when combined with fixity of purpose and regular industry, will infalliably result in a gratifying success.”

5. The literary agent was someone to aspire for, as the more successful agents were loathe to take on unknown authors who could prove unprofitable. According to advice, when the aspirant has made a name for himself and has the ability to his work on his own, then was the time to go to an agent as now the popular author–via their newly acquired agent–could demand a higher advance, more publicity and better placement in the lists. The agents’ percentage hovered around 10%, though once the author’s income exceeded two thousand a year, the agent should be willing to accept 5% on all sums over that amount.

The author with a little success would be tempted to publish their books in other countries, and while first-time authors were advised against worrying over foreign copyrights, then as today, a book that was a smash hit in England frequently fizzled in the United States, and vice versa. But in the end, the aspiring novelist turned published, had as equal a chance for success as authors today. Worries over advances, publishing profits, and so on preoccupied everyone, but thankfully, not enough to mitigate such wonderful novelists whose works have remained timeless classics in our age.

Further Reading:

Edwardian England, 1901-1914, ed by Simon Nowell-Smith

1001 Places to Sell Manuscripts: A Complete Guide for All Writers by James Knapp Reeve

Authors and Publishers: A Manual of Suggestions for Beginners in Literature by George Haven Putnam & John Bishop Putnam

Practical authorship by James Knapp Reeve

The Author’s Desk Book by William Dana Orcutt

Very interesting! It seems publishing hasn’t changed all that much in the last century or so.

Hi!

I am a spanish student. I’m doing work on an English author, Margaret D’Este, who travel to the Balearic Islands in 1906 and later published a book about his experience, “With a camera in Majorca”, in 1907, in Putnam’s Sons, London. His book was printed by Unwin Brothers, The Gresham Press, in Woking. I can not find information about it, all I know is that was accompanied by Mrs. RM King and published two books about her travels (on Corsica and the Canary Islands). If anyone has any information about it I would love to make it available. Thanks!

Hi Antonia,

Margaret D’Este’s book is available at this website. A 1905 edition of The Book Monthly states this about her previous book, Through Corsica with a Camera:

Hope this helps!

Hi Evangeline!

Thank you very much for the info, now I know that Mrs. King was her mother! If you find more information about Margaret D’Este, I would greatly appreciate you sent me. Thank you so much!

Greetings from Mallorca

Antonia