Last year The Duke of Shadows, your debut and winner of Gather.com’s Romance novel competition, was released. This year, you have two back-to-back releases. In what ways has your life changed since becoming published?

Last year The Duke of Shadows, your debut and winner of Gather.com’s Romance novel competition, was released. This year, you have two back-to-back releases. In what ways has your life changed since becoming published?

In my experience, being published wreaks its own transformation on the writing process. Suddenly I had deadlines, and professionals waiting (and wanting! what a headtrip!) to see my work, and – most amazing of all – readers inquiring about it. What had felt, for so long, like a very intimate endeavor had now acquired a public dimension.

There are obviously potential downsides to this. But once I’d acknowledged and set aside the pressure attendant on producing on a schedule, what replaced the anxiety was a sense of gratitude bordering on awe. For most of us, writing for publication is a dream we’ve nursed for a very, very long time. To have it sanctioned by a whole bunch of people who have never met you but think you were right to pursue it – that feels nothing short of miraculous.

As a doctoral student in anthropology (the best major btw), how has your academic life influenced your work? Do your peers and professors know you write romance novels, and have you ever felt pressured to write “real literature”?

You know, if there’s a relationship between them, then I think the balance of influence flows from my writing toward my academic work, rather than vice-versa.

To elaborate, I’ve always been fascinated by what our society calls popular culture. I’ve been reading and writing genre fiction since I was thirteen, and as part and parcel of my love of historical romance, I also developed an early fascination with the everyday lives and fashions of times gone by. The reason that anthropology appealed to me in the first place, then, was because the discipline recognizes the significance of popular culture — fashion, fiction, film, etc. — to our understanding of how people imagine and live their lives. (I actually entered the doctoral program with the intention of studying Indian popular cinema, and if there is any cinematic form closer to romance novels, I don’t know of it!)

In terms of its written form, anthropology is also very sympathetic to fiction. As ethnographers, our goal is to create a text that allows readers to enter a world that may appear, at first glance, utterly foreign and strange—but which, on further examination, is not so strange or opaque after all. At an elemental level, that project – of immersing the reader in an ostensibly “foreign” world and making this world seem intelligible and engaging – sounds a lot like the goal of historical romance novels.

My friends in the program know about my writing, and cheer me on. I haven’t discussed it with my professors, but I can’t imagine them pushing me to write a different type of literature. They’re the last people whom I’d need to convince of the importance of popular fiction – they are, after all, anthropologists!

The Duke of Shadows is set in 1850s India, and Written on Your Skin is set in 1880s Hong Kong. How do you maintain the balance between writing with a post-colonial view of Imperial British society yet remaining as accurate as possible to the times?

The Duke of Shadows is set in 1850s India, and Written on Your Skin is set in 1880s Hong Kong. How do you maintain the balance between writing with a post-colonial view of Imperial British society yet remaining as accurate as possible to the times?

Now, here is where I think my academic work does influence my writing, albeit indirectly.

Let it be said plainly: I have no desire to write historical fiction. I write romance, and I strongly believe that the history of the period should accentuate, rather than detract, from the development of a hot, steamy love affair that ultimately results in a lasting happy-ever-after.

But what drew me into historical romance, versus contemporary romance or romantic suspense or what have you, was the chance historicals offered to immerse myself in the “feel” of a different time period.

Now, during the 1990s, when I first discovered the genre, there were several authors who set their stories against the backdrop of the British empire. Mary Jo Putney, for instance, had a fantastic series of books (the Silk trilogy) that dealt with the Great Game in Central Asia. These books made a huge impression on me; recall that I was thirteen or fourteen when I was discovering them, and at that time, knew very little about British history.

As I grew older and my academic interests came to center on India, I was exposed to a far wider range of writing on colonialism, and I realized that Britain’s colonial project didn’t just impact Britons abroad; it was also crucial to the way British people understood themselves and their nation’s place in the world. Especially in the latter half of the century, these people were living in the most powerful empire on earth. And this shaped their lives, every day, in countless ways, even if they never set foot out of England. From the front pages of daily newspapers, to casual discussions or political debates at country weekends, to gossip about acquaintances’ private fortunes or business plans or travel itineraries—right down to the fancy items in shop windows that made little girls squeal when strolling past with their mamas, the fact of the colonies, of Britain’s dominion over distant parts of the world, was inescapable.

So. I do think we’re missing something about the “feel” of nineteenth century England when we ignore the influence of the colonies on everyday life back then. And if I want to see this in romances, it’s because I want to be immersed in the “feel” of the time I’m reading about.

Unlike The Duke of Shadows, Bound by Your Touch and Written on Your Skin both take place in England (Written on Your Skin does begin in Hong Kong, but moves to London about a quarter of the way in), and neither directly addresses colonialism.

However, I did deliberately choose to make the framing device for the external drama in each book touch upon imperial politics. In Bound by Your Touch, events are set in motion by the international trade in Egyptian artifacts, and ultimately a swindle motivated by British intervention into Egyptian politics. In Written on Your Skin, the drama originates in the motives of Irish-American expatriates who have chosen a violent approach to securing Irish independence from Great Britain. By making these issues the ever-present background for the events that drive forward the romance, what I tried to do was show how subtly and pervasively Britain’s colonial affairs infiltrated everyday life in England.

I think, on its own, this move implies a post-colonial view of empire, because part of the imperial project *in* the nineteenth century depended on the belief that Britain had achieved a perfect state of civilization, and was therefore helping out its colonies by coaxing them up the ladder toward civilizational maturity. And this belief, in turn, obviously depended on a complete denial of the notion that the colonies themselves might have an impact on everyday life in Britain. Post-colonial theorists have worked hard to show this wasn’t true — that the colonies did influence what they call the metropole, or Britain.

In my writing, however, when I show how colonial politics and life laid a shadow across life in Britain, I don’t intend it to be a political statement so much as an attempt to be true to the feel of the period — while, of course, focusing on the story of how two people fall in love despite themselves.

Based on reading The Duke of Shadows, but also the blurbs and excerpts for your upcoming releases, your heroes tend to be outsiders to society. What draws you to the outsider status in a historical romance?

Hmm. I’ve never thought about this, but you’re right, they are all outsiders, although not by virtue of their official roles. For example, James (Bound by Your Touch) could be considered the proverbial insider: he’s the golden child of high society, incredibly popular, wealthy, in line for a title. But he’s an outsider inasmuch as he loathes his “insider” status and makes a game out of seeing how far he can push it.

I suppose I’m drawn to writing outsiders because they look on their world with fresh and wondering eyes. They see things that “insiders” might never notice. And of course, I find something incredibly romantic about the idea of someone who feels so alone (whether or not he’s surrounded by an adoring crowd) but who ultimately finds that elusive sense of belonging in another person. To me, that sense of belonging is one of the great miracles that love provides us.

What elements within the late nineteenth century attract you? What has surprised you during the course of your research? Any interesting, little-known facts?

What elements within the late nineteenth century attract you? What has surprised you during the course of your research? Any interesting, little-known facts?

Awesome questions. I’m drawn to the late nineteenth century for a number of reasons. First, the widening options for women make it possible to write, in a realistic way, about heroines who stretch boundaries.

Second, people living in the 1870s and 1880s felt their world was shrinking much in the same way we do. Here’s something that surprised me: this is the period that birthed Cook travel guides. I hadn’t realized that the English middle class was regularly venturing to Egypt for vacations! That seems so…contemporary to me.

For that matter, I’m always surprised by how much racier upper-class Victorians were than we imagine them to have been. In reading primary sources about the period, I’ve come across descriptions of parlor games played during country weekends that, let’s just say, you wouldn’t want your teenage daughter playing with her friends.

But maybe that’s the key to my fascination with this period. Risque debates about sex, Bohemian artist enclaves, nightlife (clubs, bar culture, casinos, etc.), international travel — these all seem very modern. But they were on the rise in the 1880s, part of what convinced people living at the end of the nineteenth century that this period was special and exciting and also frightening and perhaps apocalyptic in terms of the best civilizational ideals. That these trends and practices coexisted with things that seem so quaint and archaic now — carriages, calling cards, balls, gas lights, aristocratic entitlement, rigid ideas of morality, a sense of the world as a map full of blank spaces, unknown wonders and dangers — that confluence is fascinating to me. This time period is right on the cusp of everything we consider familiar, but it’s still, definitively, foreign and strange. I think it’s a really exciting period to be writing about.

What books and/or authors have inspired you to be the writer you are today?

As always, I hold up Judith Ivory and Laura Kinsale as my personal heroines. Their attention to characterization and their crafting of language never fails to inspire me. Above all, I admire them for creating books that wholly immerse me in another time and place, but which each have an individual “feel” about them. I could never confuse Bliss with Dance, or The Shadow and the Star with Flowers from the Storm. Each of them offers a different and utterly absorbing experience.

While researching both Bound By Your Touch and Written on Your Skin, did you find any resources you couldn’t have lived without?

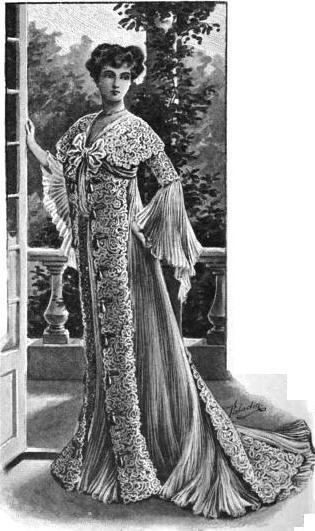

Well, first off, I’m a big fan of your site, Edwardian Promenade [Ed. TY]. I think I first stumbled across it when looking for detailed maps and descriptions of Hyde Park. You had posted a walking tour of Mayfair, and as quick as that, you went into my blogroll. 🙂 When I was writing Bound by Your Touch, I had decided that James’s closest female friend would be a so-called “professional beauty,” and once again, your blog provided invaluable information (and images!) about this phenomenon.

I’ve also found some gems among your bibliographic information. It seems we share a love of primary source material! I really do prefer primary sources to books written retrospectively about the period. This isn’t based on some conviction that primary sources are more accurate; I simply think they’re more fun to read than something full of footnotes, and they also give me a feel for the language of the period.

Now that I’m living away from campus, I can’t depend on my university’s fabulous library, but I have discovered the mother lode of primary source material in Google books. Suddenly, with a click of the mouse, I’ve got etiquette manuals from the period, guidebooks to London published in 1884, travelogues that describe Hong Kong in 1880, a female journalist’s account from 1892 of going undercover as a housemaid in various London homes, geographical dictionaries of Great Britain, issues of The Royal Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland… It is, to use a fitting cliché, an embarrassment of riches.

Random Q from the Proust Questionnaire: The natural talent you’d like to be gifted with?

Hard to pick just one! I have a difficult time visualizing things; I believe the only reason I can describe anything is because I remember the words that certain sights and objects evoke rather than the actual images I glimpsed. So, I’d love to have a more visual memory, if only so I could better remember faces. (If we’ve met before, and I walk past you without a word, it’s not because I’ve forgotten your name or our conversation – I simply haven’t matched them to your face!)

Any predictions for your future as a writer?

More historical romances, for one. I’m currently working on a book that’s coming out in May 2010, tentatively titled Wicked Becomes You. Although the emotional arc is, as always, intense, it’s also the lightest, most amusing novel I’ve ever written. I actually blame the heroine of Written on Your Skin for this turn; her story is certainly dramatic and occasionally dark, but her attitude is so playful and her sense of humor so keen that I had to scrap the proposal I’d had planned for the next book—I wasn’t in the mood to return to a heroine who took things so very seriously. (That one will have her day eventually, though!)

What’s next for you?

I’m off to India in August for a year of anthropological fieldwork. I’m curious to see how living in India might influence my writing. After three books predominantly set in England, perhaps it’s time to return to the Raj!

Although, frankly, while I managed to avoid cricket in The Duke of Shadows, I’m not sure I could pull that off a second time — which may be incentive enough to stay away from British India for a bit longer. 🙂

MEREDITH DURAN grew up enamored of British history. At thirteen years old, she made a list of life goals that included writing romance novels, trying sushi, and going to London to see Holbein’s portrait of Anne Boleyn. Now a doctoral student in anthropology, she is happy to report that all three goals have become her favorite things to do. When not studying, doing fieldwork in India, or working on her next novel, Meredith can be found in the library, browsing through travelogues written by intrepid Englishwomen of the nineteenth century. Bound By Your Touch [US]/[UK] is a July 2009 release, with Written In Your Skin [US]/[UK] following in August. Visit Meredith at http://meredithduran.com

What a great, fascinating interview! I love that Duran connects romance novels to popular culture–so art historical ;)–and that her next book is set in Hong Kong! I can’t wait!

This interview is why I love this site. Great questions, new-to-me author and loads of detail.

Great interview! I really enjoyed reading it.

I’ve never considered the connection b/t pop culture and anthropology. This is very cool.