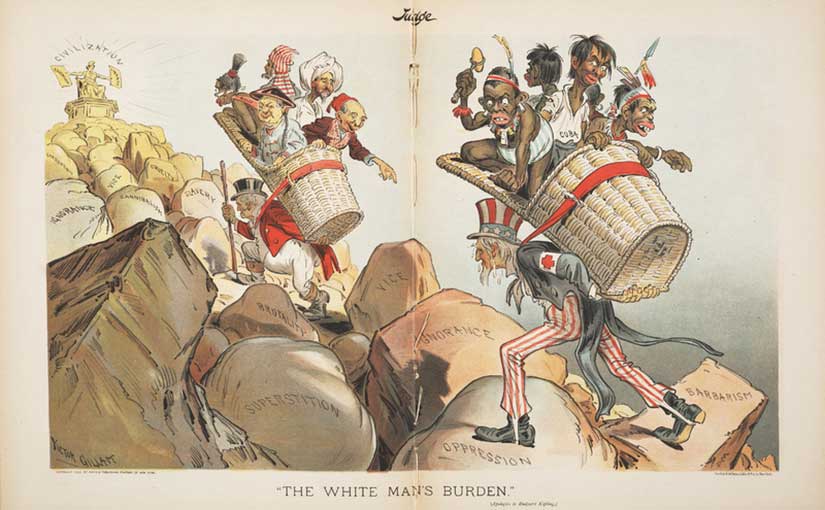

In my first post for the Promenade, I called the Edwardian Era an age of New Imperialism. What was so “new” about imperialism, you ask? Well, there were new players: Germany, Japan, and the United States, to name three. And there were new technologies: industrial transport and communication opened up the interiors of Africa and India, as well as tying together the disparate islands of the Pacific.

But one of the most puzzling aspects of New Imperialism was its doctrine: “Yes, we are here in your country, ruling your people, and pilfering your resources—but it is all meant to help you, not us.” Cue the world’s oppressed people saying: “Are you kidding me?”

Well, no, the imperialists were not kidding. In fact, they wrote poetry about how much they were not kidding. Here is Rudyard Kipling telling the Americans that it is their turn to play the game:

Take up the White Man’s burden–

Send forth the best ye breed–

Go bind your sons to exile

To serve your captives’ need;

To wait in heavy harness,

On fluttered folk and wild–

Your new-caught, sullen peoples,

Half-devil and half-child….Take up the White Man’s burden–

The savage wars of peace–

Fill full the mouth of Famine

And bid the sickness cease;

And when your goal is nearest

The end for others sought,

Watch sloth and heathen Folly

Bring all your hopes to nought.

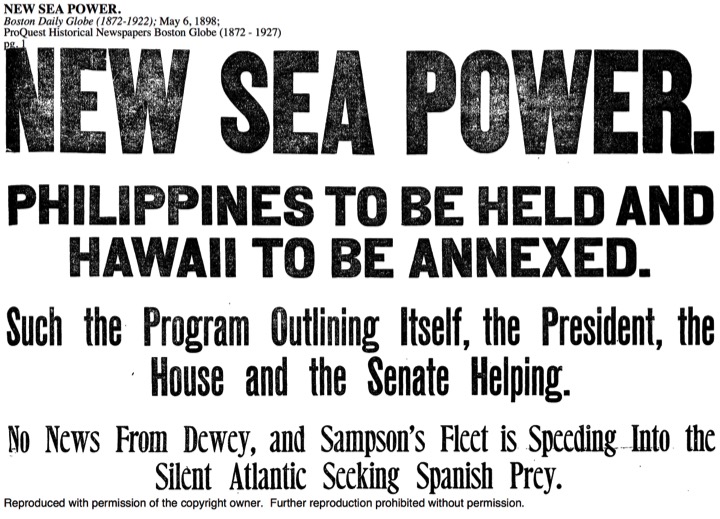

The people may hate you for it, Kipling was saying, but it is the Americans’ duty to colonize the Philippines and refashion the islands in the mold of Anglo-American civilization. You see, it was 1899. The previous year, as the opening salvo in the Spanish-American War, the United States had seized Manila. One small problem: they did not know what to do with it. Could this be the Americans’ own foothold in Asia, their economic entrepôt to compete with the Great Powers in China?

President William McKinley thought so. And, unlike those gauche Spaniards, the Americans would be enlightened rulers. He proclaimed:

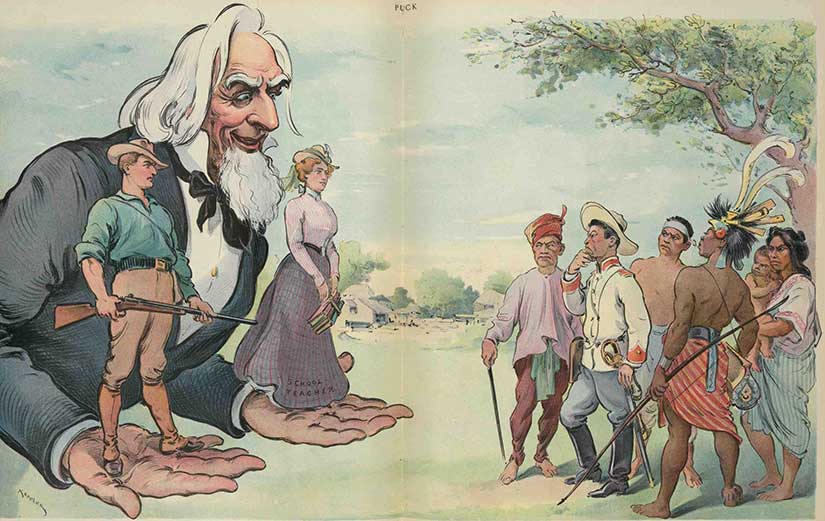

…we come not as invaders or conquerors, but as friends, to protect the natives in their homes, in their employments, and in their personal and religious rights….[The American military must] win the confidence, respect and affection of the inhabitants of the Philippines…by proving to them that the mission of the United States is one of benevolent assimilation, substituting the mild sway of justice and right for arbitrary rule. [emphasis mine]

William Howard Taft, the first civil governor of the Philippines (and eventual President of the United States), was credited with saying that the Filipinos would be our “Little Brown Brothers,” which—get this—was too nice for the tastes of most Americans. U.S. soldiers on the march in the Philippines sang in response: “He may be a brother of Big Bill Taft, but he ain’t no brother of mine.” (The ditty was eventually prohibited by officers because it did not give a great impression, to say the least.)

To be fair, there were some attempts at benevolence by the Americans. To name a few: the establishment of the first secular, coeducational public school system in the islands; the creation of American university scholarships for the brightest Filipino youth; the building of ports, roads, telegraph lines, irrigation systems, hospitals, schools, and universities; the creation of a Filipino National Assembly; several Filipino Commissioners to advise the American governors; and a Supreme Court of the Philippines, led by a Filipino chief justice. This was not really democracy, but it was not the Belgian Congo, either.

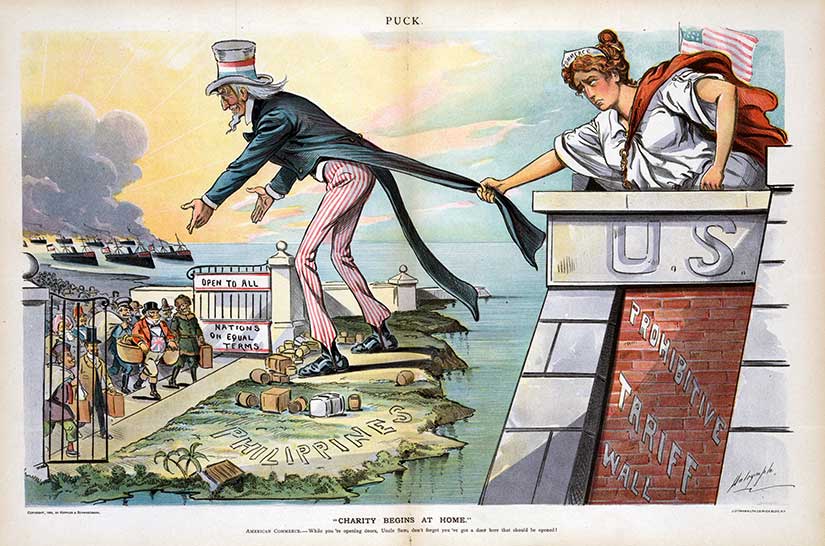

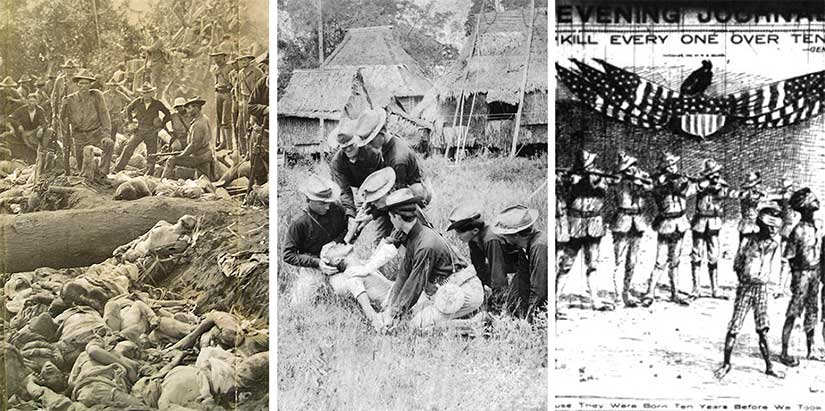

Still, there were plenty of ugly aspects to American rule in the Philippines, as you can see above. Occupation is always dirty. There was the Moro War, the water cure, and the Howling Wilderness of Samar. And, of course, there were the double-standard economic policies of the insular regime. The Americans set up a system by which American goods were sold in the Philippines tariff-free, but Filipino goods were taxed twice, both when they were exported from the Philippines and when they arrived in the United States. Where did that tariff revenue go? To pay the tab of the American administration, of course.

The hypocrisy of New Imperialism prompted English writer and politician Henry Labouchère to write the “Brown Man’s Burden”:

Pile on the brown man’s burden

To gratify your greed;

Go, clear away the “n—”

Who progress would impede;

Be very stern, for truly

’Tis useless to be mild

With new-caught, sullen peoples,

Half devil and half child…Pile on the brown man’s burden,

compel him to be free;

Let all your manifestoes

Reek with philanthropy.

And if with heathen folly

He dares your will dispute,

Then, in the name of freedom,

Don’t hesitate to shoot.

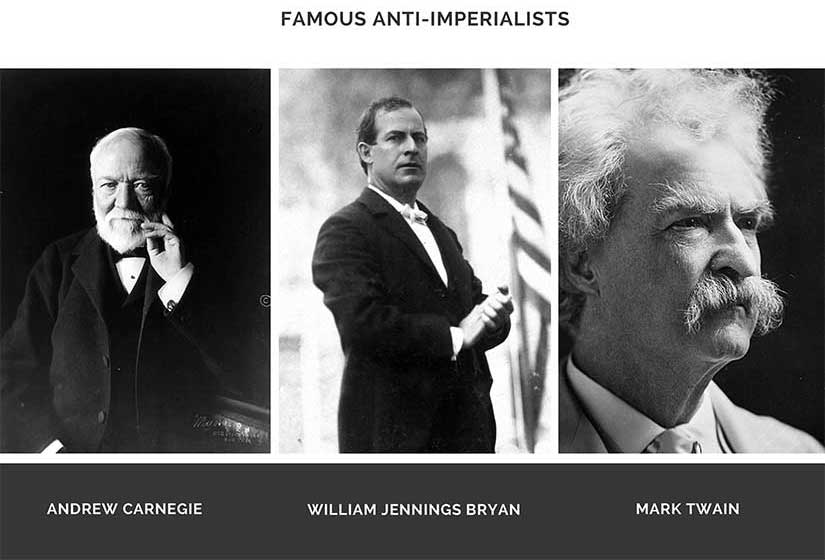

Before you pat Labouchère on the back for his progressive skewering of Kipling’s motives, do know that he was an homophobic campaigner whose most lasting legacy was the Labouchère Amendment that made all sexual activity between men a crime. (This is the law that Oscar Wilde and Alan Turing were prosecuted under.) And Labouchère was not the only anti-imperialist who might disappoint our modern sensibilities. Both Andrew Carnegie and William Jennings Bryan were anti-imperialists, but their opposition was actually based on racism of all things. Carnegie wanted us to only take land that would “produce Americans, and not foreign races,” and Bryan worried about Chinese and Filipino immigration “exciting a friction and a race prejudice” that would damage America’s homogeneity.

Before you despair, though, let’s move onto Mark Twain, whose essay “To the Person Sitting in Darkness” is one of the best pieces of political satire ever published, in my opinion:

Shall we? That is, shall we go on conferring our Civilization upon the peoples that sit in darkness, or shall we give those poor things a rest? Shall we bang right ahead in our old-time, loud, pious way, and commit the new century to the game; or shall we sober up and sit down and think it over first? Would it not be prudent to get our Civilization-tools together, and see how much stock is left on hand in the way of Glass Beads and Theology, and Maxim Guns and Hymn Books, and Trade-Gin and Torches of Progress and Enlightenment (patent adjustable ones, good to fire villages with, upon occasion), and balance the books, and arrive at the profit and loss, so that we may intelligently decide whether to continue the business or sell out the property and start a new Civilization Scheme on the proceeds?

In a similar vein, Twain also “updated” the lyrics of the Battle Hymn of the Republic, Julia Howe’s abolitionist hymn, to more properly reflect what he felt Americans had been doing in the Philippines:

Mine eyes have seen the orgy of the launching of the Sword;

He is searching out the hoardings where the stranger’s wealth is stored;

He hath loosed his fateful lightnings, and with woe and death has scored;

His lust is marching on.

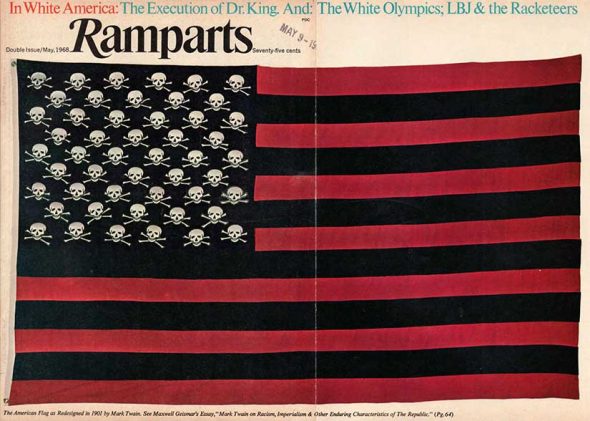

And, if that was not enough, Twain redesigned the American flag to include skulls and crossbones instead of stars. Twain gives us some faith that not every American bought into the plunder-but-call-it-progress ideology of New Imperialism.

This post can also be found at my own author website here, along with more about my Sugar Sun series, steamy romance set in the Philippine-American War. Because history + kissing = my job.

I wrote a portion of my senior thesis on this very topic. It’s amazing to compare American Imperialism to the European mode, and how the US was determined to present its encroachment in Asia and Latin America/Caribbean as benign and harmless compared to Europe!