Light for the Nursery

Baby is at last counted worthy to share with its elders the advantages of all the health-giving devices of the twentieth century, and the deplorable remark, ” What a pity to turn this fine room into a nursery! ” is now but rarely heard. This is as it should be, for it is as impossible to rear fine, healthy children in dark, airless rooms as it is to rear healthy plants in out-of-the way corners, inaccessible to sun and air.

No matter whether engaged in the momentous task of preparing the nursery for its first tiny occupant, or whether it is already overflowing with little olive-branches, see, at all events, that the aspect and position of this all-important room is as good as it can be.

The Aspect

Never mind which way the spare room faces, or how many steps lead up to it, but choose a south or south-west aspect for the children; for, no matter how costly and hygienic the fittings, a sunless room facing north will never make a healthy nursery. The excuse is made sometimes that a sunny room is too hot in summer, and makes its youthful inmates pale and listless. This is certainly the case. But our English summers are, alas! too short; and even if the nursery cannot be changed during the heat, at all events some other room can often be temporarily given up, or, best of all, the children kept in shade and shelter out in the open air.

If it can be managed, the nursery ought not to overlook the street – a quiet room is very necessary – and never be persuaded to ” sky the little ones. Have you ever noticed that in hundreds of homes the window-bars that denote the position of the nurseries are often on the highest story, in order to banish childish voices and restless feet as much as possible?

Now, rooms at the top of a house are often less lofty, have smaller windows, gain additional heat and cold from proximity to the roof, and last, but not least, receive all the used-up air from the lower rooms, because heated, impure air rises. Cramped nursery quarters are very undesirable.

The Necessity Of Ventilation

The size of a room for a nurse and one child should not be less than fourteen or fifteen feet square, and eleven or twelve feet high. Where this is quite unattainable, take extra precautions to ensure good ventilation. Pure air, fresh air, is as important for children as food. True, they may live in vitiated air that has been breathed in and out and contaminated by other human beings, but only at the expense of mental and physical health. Well-ventilated rooms are easily secured in quite simple ways.

Firstly, there must be an open chimney in the room, for this acts as a most efficient ventilating shaft. Therefore, the register must never be closed, or the chimney blocked in any way. Secondly, direct that the upper sashes of the windows are left open night and day – and see the order is carried out. If the weather is too inclement or there is any special reason against doing this, have ready for such an emergency a piece of wood the width of the window and about four inches deep.

Open the lower sash, fit in the piece of wood, shut the window down on to it, and a space will be left between the upper and lower sashes in the vicinity of the fasteners through which the outer air will rise without draught. Never imagine that fresh air means draughts through badly-fitting windows and ill-laid floors. If these exist, tack the india rubber tubing made for the purpose, and costing but a few pence per yard, under the doors, etc., and fill cracks in the floor with putty or cement.

Nursery windows should be protected by outside iron bars, for children simply love to look out, and in no other way can their safety be ensured. Supposing bars are not possible for some reason, hammer a strong nail into the window frame above the lower sash, so that it cannot be raised more than about six inches. The most hygienic plan is to have the nursery windows free from blinds, as, with the exception of the Venetian variety, they all exclude air, and the latter, alas! are veritable dust-traps unless constantly washed.

Still, it is convenient to be able to screen the windows at times, in order to soften the light or make the room cosy in winter; so soft casement cloth curtains, in tints to harmonise with the room, are often used, for they wash perfectly, and only need to be plainly ironed.

The Ceilings And Walls

A few years ago whitewashed ceilings were thought good enough for anybody, but baby nowadays has his painted in white or pale cream enamel, washable distemper, or covered with white washable paper. If, however, the old method is preferred, the whitewashing should be done every spring. Ceilings and walls give wide scope for artistic and original ideas, as long as the rule that ideal nurseries must be washable throughout is always remembered. Perhaps the greatest favourite for nursery-wall coverings is some form of washable distemper, or enamelled paint in pale tints, with decorative bands or friezes of paper made in designs of quaint figures, animals, birds, etc., affording the youngsters something bright and entertaining to look at during meals or rainy days.

If liked, washable papers illustrating nursery rhymes, etc., can be used instead of the self-coloured paint or distemper; but they do not make a restful background, and need to be purchased from good firms, or the designs and colourings injure, instead of educate, the children’s perception of colour and form. In some nurseries the dado is made of pretty oilcloth, fastened to the wall with a dado rail above of a darker contrasting colour. This scheme is simple, costs little, is very strong, and easily kept clean.

The Important Question Of Floors

What shall our babies walk and crawl on is another absorbing question. Try a good cork carpet with a pattern (not self-coloured, as these show the dust too much). It is warm, wash-able, strong, and pretty, and affords no resting-place for the dust fiend. A few washable cotton rugs in blue and white or other colourings can be laid down here and there, but care must be taken that children do not trip over them.

Baby’s Furniture

There is still a tendency to relegate large, old, cumbersome pieces of furniture to the nursery, either because it is roomy and comfortable, or because it has become a sort of nursery heir-loom; but it is doubtful if either reason is sufficiently good to justify their presence in valuable space that ought to be occupied by air. So far as comfort goes, nothing can beat the modern nursery furniture now procurable from many good firms. Simplicity is the rule, and furniture of best quality is made in plain oak or stained wood, for painted and highly polished surfaces too soon show the wear and tear of nursery customs.

Rounded corners to everything are necessary for sharp-pointed edges have resulted in many a serious cut and scar. Supposing the furniture now in use is of the latter description, a cabinet-maker will very soon remedy the danger. Miniature nursery tables, chairs, etc., are very popular. They are made in wood or cane, and are more comfortable and safer than high tables and chairs.

A cosy, broad sofa is an invaluable possession in the nursery. An aching head or bruised limb can be petted on it so well without keeping the child in bed, and it provides a too quickly-growing boy or girl with means of obtaining the necessary rest, not to mention its Splendid capacity for acting as a “ship,” “train, “desert island,” etc. A toy cupboard of some description is essential, or the nursery can never be called ideal. The shelves ought to be low enough to be within easy reach of the children. Not only does it help to keep the nursery tidy, but it is also a never-ending source of delight to the chicks; for is it not their very own, in which they can hoard unchecked the hundred and one treasures that unfeeling nurses are apt to catalogue as rubbish?

A toy table is considered a very great treasure. It may easily be fashioned at home. There must be an edge round to prevent marbles, etc., rolling off; it must be low enough for the children to be able to sit at it on the floor with their feet under it. It should have castors, so that it can be easily pushed about, and it must be sufficiently strong to bear the child, who will inevitably use it as a seat.

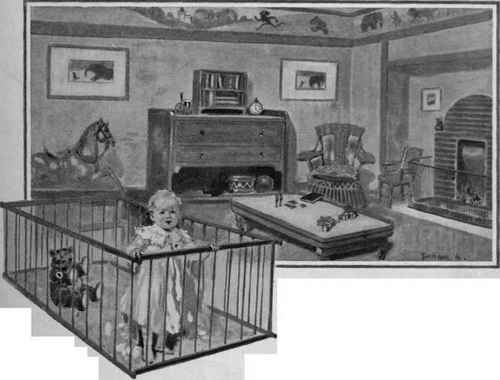

One of the latest and most successful additions to the nursery is a sort of sheep-fold, in which baby can crawl about without injury to himself or worry to a busy nurse or mother. A crawling-mat made of thick, soft material, on to which are appliqued animals and birds cut out of some bright-hued scraps, is also very useful. Babies simply love to roll and crawl on these mats, and hold contented converse with the zoological specimens adorning their surface.

Nurse, on her part, will demand a big cosy chair, in which she can cuddle and pet her small charges, a lock-up medicine cupboard to fix on the wall, far from the reach of any inquisitive fingers, and a reliable clock, but not one that strikes or has one of those aggravatingly aggressive ticks.

A very high fireguard is an absolute necessity, and one that covers the grate right over is excellent, for children seem to find anything to do with fire irresistibly attractive. If liked, an outside rail may be affixed to the guard, on which a few little garments may be warmed; but on no account allow the nursery to be used as a laundry or drying-room, for this practice, beloved by inexperienced nurses, renders the air steamy and unwholesome. Besides this there is the danger from fire. Food should never be stored in the nursery, but the nurse will want a simple dresser-like cupboard in which to keep a tin of biscuits and a few other items, as well as the children’s own special cups, plates, table-linen, and so forth.

Unless a place is provided for these, it is unreasonable to expect an orderly nursery. A few good pictures on the walls have a real educational value. Crudely-coloured and badly-drawn prints, etc., should never be permitted, for they do untold harm by wrongly forming the child’s idea of art and beauty.

In conclusion, the ideal artificial light for the ideal nursery is electric light; but if this is unattainable, provide wall-lamps with metal reservoirs – not glass or china – and a safety apparatus for extinguishing the flame if the lamp overturns. Use the best oil, and have the lamp fixed in a strong holder on the wall out of the children’s reach. Gas, though clean and most convenient, vitiates the atmosphere, and is therefore most harmful for the children’s room.

Do not allow many plants or flowers in the nursery. Above all, they should not be placed in the window where they obstruct the light and air. A few geranium cuttings or a pot of musk provide interest and amusement, and the unfolding of a new leaf or a blossom gives instruction in simple plant life, but a nursery should never be crowded with growing things. The children’s health is the most important consideration of all, and anything which prevents free circulation of the air is deleterious. Never allow anything in the way of rubbish to accumulate.

— Every Woman’s Encyclopaedia v1

I liked this: “washable papers illustrating nursery rhymes can be used instead of the self-coloured paint or distemper; but they do not make a restful background, and need to be purchased from good firms, or the designs and colourings injure, instead of educate, the children’s perception of colour and form”.

In all that overly precious protection of babies and toddlers that we can see in the Every Woman’s Encyclopaedia, the interest in children’s learning sounded quite modern and sensible.

They were. The Edwardian era was one of the first times where parents were supposed to view their children as individuals to be nurtured and cultivated, as opposed to being extensions of themselves.

Do you know what year this article was published in th Every Woman’s Encyclopaedia?

The copyright date for the volumes are ca. 1911-1912.