Life in the trenches was not a single, uniform experience for Allied troops in France, nor was it a strictly British experience; it was also not one long and relentless barrage of shells, grenades, snipers, and gasses from the enemy until one was wounded or killed. As Downton Abbey’s second season opens, we see Matthew in the thick of the Somme Offensive (July-Nov 1916), and later battles touched upon include the Battle of Arras (Apr-May 1917), the Battle of Passchendaele (July-Nov 1917), and the Spring Offensive (Mar-Jul 1918) and Hundred Days (Aug-Nov 1918).

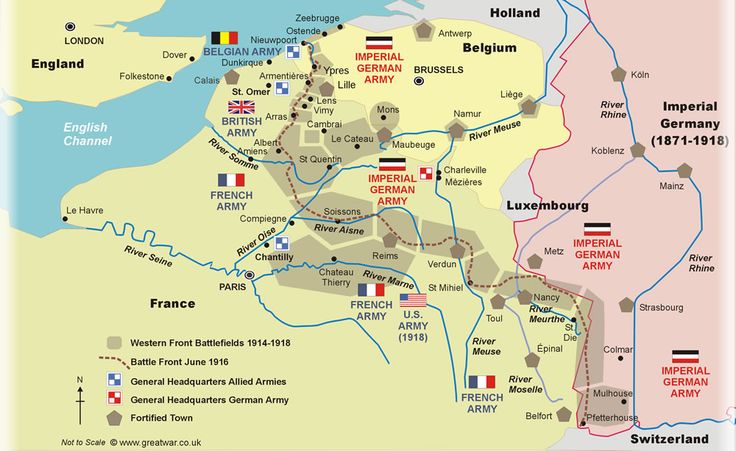

The following image gives a visual of the Western Front and its important battles:

When war was declared in August, many believed it would be over by Christmas, and thousands of idealistic and patriotic young men rushed to recruiting stations determined to smash the Huns and restore peace and order to the world. Unfortunately, despite numerous warnings and warmongering over the past twenty years as Germany armed itself, little had been done to prepare for a war of any length.

Yes, Richard Haldane had modernized the Army and Winston Churchill did the same for the Navy, but the course of bureaucracy was slow, and the appointment of Sir John French of the British Expeditionary Force (BEF) and Field Marshall Lord Kitchener as Secretary State of War–venerated veterans of 19th century battles–were both largely “romantic choices.” French, a believer in the “‘cavalry spirit’, in which all was achieved by dash and the terrifying effect of a charge with lance and sabre” had a “distrust in new weapons and new methods of war”, whereas Kitchener did foresee a long, arduous war, but was secretive, autocratic, and overall difficult to deal with.

It was under the command of these two men that the first wave of troops journeyed to the Western Front.

Nevertheless, Lord Kitchener was seen as an imperial hero, and his recruitment posters appealed to the half a million men who enlisted by mid-September. Of these half-million were thousands of public school and university students who, by dint of their rank and background, were immediately taken on as junior officers (to put this in proper scope: all but eighteen of the boys who left Winchester between 1908 and 1914 were serving by 1915). In August 1914, the BEF mobilized its troops, and “on the nights of August 12th and 13th, 90,000 men, 15,000 horses, and 400 guns marched between the large canvas screens that masked the approaches to the Southampton docks, to be carried away to Le Havre, Rouen, and Boulogne.”

Almost immediately, the BEF was in the thick of battle and “by the end of 1914—after the battles of Mons, the Le Cateau, the Aisne and Ypres—the old regular British army had been wiped out, although it managed to stop the German advance.”

By September 1914, both sides quickly realized the war was not to be of a short duration, and from the First Battle of the Aisne to the First Battle of Ypres (Oct-Nov 1914), each side attempted to find an open flank throughout north-eastern France, which resulted in a 200 mile front line of trench fortification. By the end of the war, this extended from the coast of France to the Swiss border.

The Allied trenches and the German trenches “mostly ran alongside each other, and varied from a distance of over a kilometre to as little as 15 metres apart, such as at Hooge, near Ypres.” There was also a considerable difference between the two, as the Germans immediately went on the defensive and built a system of elaborate and up-to-date trenches with “concrete…electricity, telephone lines and relatively roomy accomodation.” In contrast, the British and French trenches were initially hurriedly done, and became more sophisticated as the war wore on.

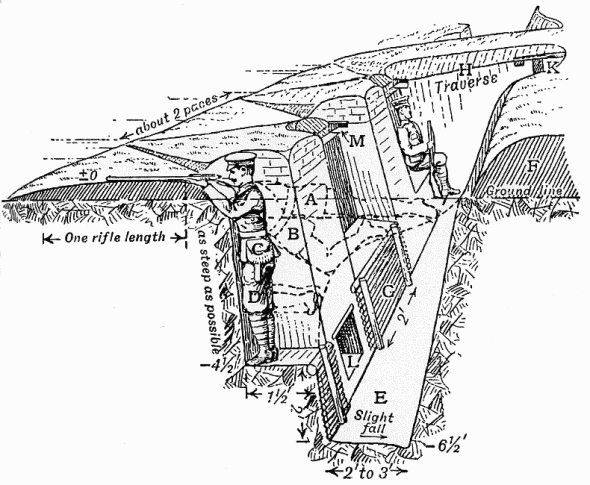

Trench Construction

As the front line stabilised at the end of 1914, trench construction would gradually become more elaborate and sophisticated. Trenches would become deeper and dug outs would be provided to allow soldiers to eat, drink and sleep closer to the front line.

Trench construction was an arduous task. On average, it would take 450 men six hours to build a section of 250 yards of trench. They would then have to add the paraphernalia of other materials; barbed wire, board walks, alarm bells and sand bags to prevent the sides from collapsing. Space had to be found for stores, first aid posts, communications equipment and headquarters posts. The trenches were never built in straight lines. They were usually zig zagged in order to stop enemy troops who had entered a trench system from firing down the length of the trench line.

Over time, communication and support trenches were added. These would allow for reserves to be brought up to the front line in relative safety. They could also allow for secondary lines of defences for troops to fall back to if necessary.

The Allies used four “types” of trenches. The first, the front-line trench (or firing-and-attack trench), was located from 50 yards to 1 mile from the German’s [sic] front trench. Several hundred yards behind the front-line trench was the support trench, with men and supplies that could immediately assist those on the front line. The reserve trench was dug several hundred yards further back and contained men and supplies that were available in emergencies should the first trenches be overrun.

Connecting these trenches were communication trenches, which allowed movement of messages, supplies, and men among the trenches. Some underground networks connected gun emplacements and bunkers with the communication trenches.

German trench life was much different. They constructed elaborate and sophisticated tunnel and trench structures, sometimes with living quarters more than 50 feet below the surface. These trenches had electricity, beds, toilets and other niceties of life that contrasted sharply with the open-air trenches of the Allies.

In between stretched “No Man’s Land,” which varied in width based on the distances between the trench lines. This area was heavily fortified by barbed wire, mortar shells, land mines, and snipers, and after numerous trips “over the top,” it would be riddled with the dead and the dying and the wounded–the last of whom stretcher bearers were required to fetch beneath the assaults. This was the hellish surrounding in which the soldiers lived, and the conditions inside of the trenches were no better.

The first irritation the troops dealt with were infestation of lice and of rodents. Lice were a never-ceasing problem, getting into uniforms, hair, and clothes; the only way to get rid of them was to burn them out with a match. Lice also increased the mortality rates within the trenches, as they caused “Trench Fever, a blood-borne infection caused by a bacterium known as Bartonella quintana.” Since this infection mimicked the flu, “with increased pain and a high fever and only rest, usually away from the front-line, could assure that the condition could be treated.

Full recovery usually took up to twelve weeks, but because the pesky lice were not actually identified as the culprits of Trench Fever until 1918, some men it was assumed, had just a high fever associated with another illness. As such, many succumbed to the disease whilst recuperating away from the trench due to inadequate medical treatment.” Rats were even more disgusting, gorging on human remains and nibbling through rations and on the men’s exposed parts, as Raymond Asquith described in a letter: “this is no place for those who mind rats, as the little rascals are very numerous, well-nourished and daring.”

A lack of hygiene was inevitable as there were limited water resources and using the latrine (which was really just a large bucket in a side trench) risked exposure to enemy fire. When the weather turned nasty, the trenches could be filled–even to waist deep!–with water, sludge, and mud, also contributing to the susceptibility to diseases like dysentery.

The most grievous wound one could catch in these conditions was Trench Foot–“a fungal infection that could turn septic, resulting in amputation”–though as conditions improved in 1915, cases trickled almost to a halt. Food rations were also an issue, though the Government made an effort to feed the Army adequately. It was difficult to get food from the field kitchens to the front line during the thick of battle, but during “stand down” time, food was hot and plentiful.

Surprisingly, life in the trenches was not permanent, and in some areas along the front line, the war was relatively light and easy. A typical British soldier’s year could be divided as follows:

- 15% front line

- 10% support line

- 30% reserve line

- 20% rest

- 25% other (hospital, travelling, leave, training courses, etc.)

It also was not unheard of for officers to leave their regiments for other positions, such as translator, aide de camp, intelligence work, etc etc.

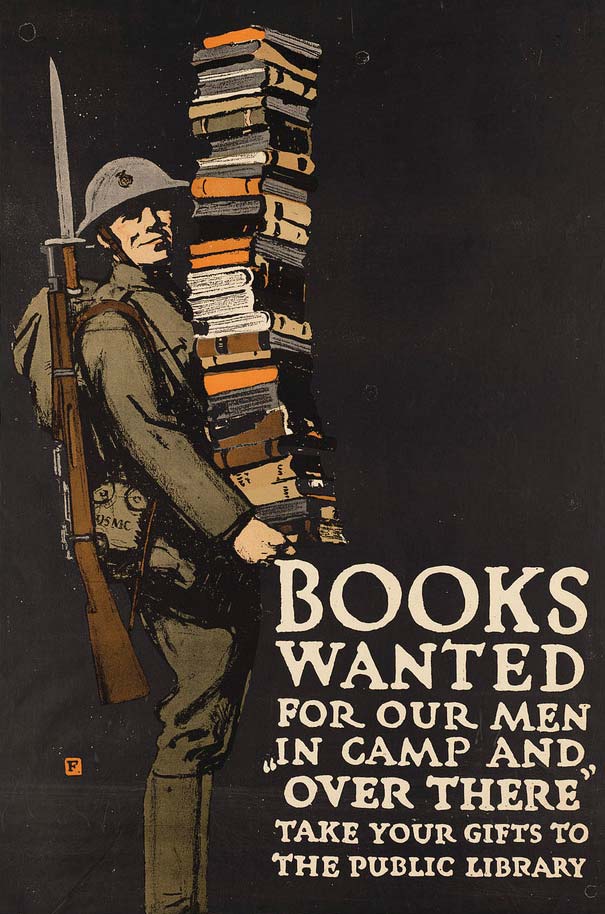

When not in battle, soldiers passed their time by burying the dead, rebuilding trenches, patrols, sentry duty, reading letters from their loved ones, reading books, repairing uniforms, eating, raids into No Man’s Land, playing cards or football (soccer), and chatting. In spite of the squalor and death, most still found humor–albeit tinged with plenty of black–in their situation, and from this birthed the Wipers Times.

So named because British troops could not pronounce Ypres (ee-pre), it was founded in 1916 by the 12th Battalion Sherwood Foresters after they discovered an abandoned printing press in Belgium. The Wipers Times was full of satirical advertisements, articles, and lyrics, as well as the infamous “war poems” and personal reflections on the war and life in general. The paper was produced at irregular intervals from February 1916 to February 1918, the title of the newspaper shifting as the division moved to another part of the Front Line.

Trench life could be cruel, deadly, and dull, but contrary to popular images of the Great War, it was not permanent or under constant siege.

Further Reading:

Downton Abbey Season 2: A World War One Guide to Rats, Shell Shock, and Barbed Wire – Jane Austen’s World

Sources

The Children of the Souls by Jeanne Mackenzie

The Trenches

What were the differences between the German and allied trenches in WW1?

Life in the Trenches

Soldiers’ Food in the Trenches

Satirical Magazines of the First World War: Punch and the Wipers Times

The Wipers Times: The Complete Series of the Famous Wartime Trench Newspaper

My Second Year of the War by Frederick Palmer

WWI – BBC

The First World War, 1914-1918 – Casa Histories

Trench Warfare

British Trench Warfare 1917-1918

Diary of Trench Life and The Somme

First World War: Trench Warfare

Life in the Trenches of World War One

That particular trench Matthew was in seemed pretty settled!

There were complaints in the UK about how clean the trenches were, but hey, the show wasn’t going for absolute realism–otherwise we would have seen dead bodies littering the trenches and No Man’s Land, with body parts and eyeballs and nasty rats eating them!

Great post, Evangeline, which describes the situation better than I could. While it is true that there was no constant shelling, and that the men spent many hours of boredom in between battles, they were never quite sure what would hit them – death by surprise attack or sniper fire, or from disease. I can’t imagine what it was like for a young 19 year old accustomed to working on a farm or at a desk job in the City, to be transported to such a hellacious situation, especially during rainy weather when so many of the trenches were dug at water level or below.

Your post was just as excellent!

And I do agree. I can read letters and diaries from the period, and watch pictures and movies, but my secondhand experience pales considerably from what those young men–and women– went through.

This post was especially informative – thank you so much for having it ready to go the day after Downton Abbey’s Season 2 premiere! I am especially interested in the Great War, as I had three ggreat uncles (all brothers) who died at this time: one contracted tuberculosis as a Merchant Seaman, one died in the Royal Navy when his ship hit a mine in the Moray Firth, and the other died in the field as a gunner in Belgium.

You’re welcome!

Honestly, I avoided looking into WWI because of popular images of the war (there’s a great book about how the media has shaped our perception of WWI). And to lose three men must have been devastating for your family. Because WWI wasn’t as brutal on America as it was on Europe, it’s so easy to feel removed from the carnage, but stories like yours always remind me of how connected we all our, regardless of geography. Thanks for stopping by and sharing your family story.

Actually, those three brothers were English (my mother is from England). My mother remembers seeing a photo as a child of all seven brothers, and being told they had all died with the exception of her grandfather. So I have been researching to find out what really happened. All six joined the military, but thankfully only three died during WWI.

Excellent information. Thank you for furnishing this.