Today, society is shocked by the revelation of Bernard L. Madoff’s “Ponzi Scheme,” and many sources compare his fraud to that of Richard Whitney. However, Madoff is closer in relation to the infamous Le Grande Thérèse than the sad case of Whitney. In 1902, a political and financial scandal rocked the French nation when it was discovered that Madame Thérèse Humbert (née Aurignac), daughter-in-law of the deceased Minister of Justice, had swindled nearly 100 million francs from the French government and its citizens over twenty years. How did this woman, who was not particularly beautiful, educated, or well born, manage to defraud scores of people, ranging from the brightest and sophisticated of French society to the simplest?

Today, society is shocked by the revelation of Bernard L. Madoff’s “Ponzi Scheme,” and many sources compare his fraud to that of Richard Whitney. However, Madoff is closer in relation to the infamous Le Grande Thérèse than the sad case of Whitney. In 1902, a political and financial scandal rocked the French nation when it was discovered that Madame Thérèse Humbert (née Aurignac), daughter-in-law of the deceased Minister of Justice, had swindled nearly 100 million francs from the French government and its citizens over twenty years. How did this woman, who was not particularly beautiful, educated, or well born, manage to defraud scores of people, ranging from the brightest and sophisticated of French society to the simplest?

Let us return to Thérèse’s childhood.

The seeds of charm and deception were sown in the person of her father, an impoverished nobody who liked to tell the tale of his secretly noble background: his name was not Aurignac, but d’Aurignac, and his home was not the small cottage in which he lived, but a mighty chateau in the Auvergne. Unfortunately, he had quarreled with his parents who cast him out, but after his death, his children would inherit the castle, title, and fortune of d’Aurignac. As proof to any unbelievers, he would allow them a peek at a brass-studded chest in which he stated lay all the documents necessary for his children to claim their fortune. Thérèse, based on the wild imaginings of her father, grew up thinking she was of noble blood, and spun her dreams and hopes on that future inheritance. It was a cruel and bitter blow to her pride when after the death of her father the chest proved to contain nothing more than a brick.

Humiliated, and even more so when she was forced to find work to support her three younger siblings, Emile, Romain, and Marie, Thérèse could only bide her time while she plotted to restore herself to the “rightful” place she felt she deserved. Good fortune came in the form of a position as washerwoman in the household of a half-aunt, who was married to Gustave Humbert, the Mayor of Toulouse. There she met Humbert’s son, the weak-willed Frederic. Thérèse stroked his ego, encouraging the sensitive young man to pursue his dreams, for she said a kind old lady, Madame de Mariotte had bequeathed her a chateau, a large estate, and riches beyond imagination. When she turned 21, she could inherit and give it all to her dearest Frederic. He swallowed her sympathy and lies and immediately proposed. When his father objected, the couple eloped and moved to Paris.

Humiliated, and even more so when she was forced to find work to support her three younger siblings, Emile, Romain, and Marie, Thérèse could only bide her time while she plotted to restore herself to the “rightful” place she felt she deserved. Good fortune came in the form of a position as washerwoman in the household of a half-aunt, who was married to Gustave Humbert, the Mayor of Toulouse. There she met Humbert’s son, the weak-willed Frederic. Thérèse stroked his ego, encouraging the sensitive young man to pursue his dreams, for she said a kind old lady, Madame de Mariotte had bequeathed her a chateau, a large estate, and riches beyond imagination. When she turned 21, she could inherit and give it all to her dearest Frederic. He swallowed her sympathy and lies and immediately proposed. When his father objected, the couple eloped and moved to Paris.

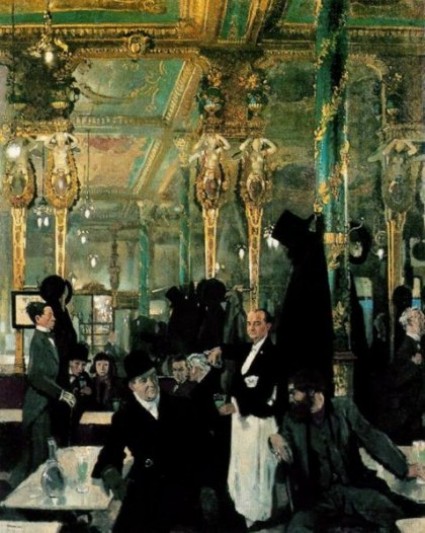

In Paris, the couple lived well beyond their means, dining in the best restaurants, taking the best seats in the theatre, and buying expensive properties. If it wasn’t for Frederic’s father, now the Minister of Justice–he could not afford the scandal–who stepped in and paid their debts, the Humberts would have been arrested by their creditors. After their bills were paid, Thérèse noticed something: simply seeing money calmed her creditors and with the prospect of cash available to pay bills, they seemed more inclined to lend to the young couple. It was a situation ripe for exploitation.

A few months later, Thérèse received a windfall: she had been left millions by a rich American named Crawford whom she’d met in 1879. According to Thérèse, on a train ride, she heard groans from the next compartment. She entered into it by climbing along the outside of the train. There she found a man who was having a heart attack. When she had revived him with her smelling salts, the man told he was an American millionaire named Robert Henry Crawford. He was eternally grateful and promised to reward her some day. Two years later in 1881, she received a letter that stated that Crawford had died and made her beneficiary of his will.

A few months later, Thérèse received a windfall: she had been left millions by a rich American named Crawford whom she’d met in 1879. According to Thérèse, on a train ride, she heard groans from the next compartment. She entered into it by climbing along the outside of the train. There she found a man who was having a heart attack. When she had revived him with her smelling salts, the man told he was an American millionaire named Robert Henry Crawford. He was eternally grateful and promised to reward her some day. Two years later in 1881, she received a letter that stated that Crawford had died and made her beneficiary of his will.

However, there were conditioned on the inheritance: her sister Marie was to receive a third of the state, as were two cousins of Mr. Crawford; no part of the legacy was to be touched until Marie’s 21st birthday; lastly, the will would not be valid unless one of the nephews married Marie. In a blaze of publicity, Thérèse installed a fireproof safe in the bedroom of her new home in the Avenue de la Grande Armée, hired a provincial magistrate to act as notary, and placed the documents and securities in the safe. The magistrate testified the procedure was sound and legal, and then Thérèse sealed the safe with hot wax. It would not be opened until her sister’s 21st birthday. The brilliance of this move was immediate: all doubt vanished about the claim and Thérèse was able to borrow as much as she liked on the strength of it. She and Frederic went on a spending spree, buying three country mansions, a steam yacht, countless hats and clothes, and thousands of other things. In total, they borrowed 50 million francs on the strength of an empty safe.

Thérèse furthered her deception by borrowing almost twice as much on the initial 50 million francs. Any doubts that could possibly arise about the legacy were allayed by the various legal technicalities which arose: the Crawford cousins might not decide who would marry Marie, and Marie might declare she didn’t want to marry either one of them.

Because of her father-in-law, the Humberts had political connections and assets to launch themselves into the upper echelons of French society. Sophisticated Parisians were just as taken in by Thérèse as Toulousians had been and more importantly, they were equally prepared to advance her credit. The Humberts bought a newspaper, which their loyal friend Armand Paraye ran as a radical muckraker, and used it as a vehicle to support the progressive cause of her father-in-law, and even campaigned to have Frederic elected as Republican deputy to the French parliament. Before long, Thérèse had become on the of the most esteemed hostesses in the nation with presidents, ministers and plutocratic financiers all paying court to her in her opulent Paris home.

But Thérèse grew greedy. She established an insurance company, the Rent Viagere, in 1893, that was backed by little more than a fancy prospectus with unauthorized pictures of the President of South Africa and the Pope. This scheme drew in many more, often smaller investors, and was aimed at peasants, small businessmen and others unable to save large amounts of money for their final days. It succeeded not only because it offered large returns from small investments, but because it was seen to honor its settlements quickly and without fuss. Unfortunately, the insurance company was a sham: its deposits and payments received were left unsecured, and any settlement which had to be paid was taken directly from these incoming payments. More than 40 million francs were raked in, most of which went into Thérèse’s private bank account, which Thérèse and Frederic used to slowly pay off their loans with income the insurance firm produced.

Thérèse utilized the Crawford cousins to allay any fears about the legitimacy of the inheritance. To keep creditors from calling in their debts, every time one threatened or at least looked to threaten, a Crawford suddenly called, wanting to buy the debts in order to own all of the Humberts’ chits in order to ruin the family. The creditors would instantly refuse, thinking that a debt that valuable would be better off in their hands, and this would appease them.

But the chips were about to fall. Suspicion was aroused when Girard’s bank in Elbeuf, which had made substantial loans to Thérèse in the 1880s and 1890s, began to experience losses and Girard called on Thérèse for payment on the loans made to her, pleading he would go bankrupt otherwise. Thérèse cared little for his bankruptcy, and when he shot himself in despair, a case was opened into the Humbert affairs. Rene Waldeck-Rousseau, one of the most distinguished members of Paris bar and a republican politician, conducted the effort to collect the largest of the outstanding debts and came to know the Humberts this way. As his inquiries spread about the Crawfords, the Humbert,s and the Girard loans, he began to feel doubts.

However much she’d shored up any doubts with investors and her creditors, Thérèse’s story had many holes in them, not the least the fact that no one had ever seen truly the Crawfords, nor could anyone provide an address for them. Way back in 1883,  Le Matin published a skeptical article, but Humbert’s powerful father-in-law backed up her story. Humbert claimed that the Crawfords had sued him so that she would have to place her part of the inheritance in the Crédit Lyonnais bank. After a lengthy litigation, during which the two Crawford nephews, Henry and Robert, appeared in court, it was ruled that the locked safe should remain in Thérèse Humbert’s possession. When Jules Bizat, official for the French bank, asked Humbert how she had invested her money, she claimed that it was in government bonds. Bizat checked and found that it was not the case.

Le Matin published a skeptical article, but Humbert’s powerful father-in-law backed up her story. Humbert claimed that the Crawfords had sued him so that she would have to place her part of the inheritance in the Crédit Lyonnais bank. After a lengthy litigation, during which the two Crawford nephews, Henry and Robert, appeared in court, it was ruled that the locked safe should remain in Thérèse Humbert’s possession. When Jules Bizat, official for the French bank, asked Humbert how she had invested her money, she claimed that it was in government bonds. Bizat checked and found that it was not the case.

By the late 1890s, Thérèse’s creditors noticed that the supposed amount of the inheritance would never be able to cover all the loans and legal costs. Le Matin began a campaign of exposure and the court proceedings moved without delay. Humbert’s creditors sued her in 1901, and the next year the Parisian court gave an order that the fabled safe would be opened to prove the existence of the money. The safe was found nearly empty, containing only a brick and an English halfpenny. The scandal rocked the French financial world, and thousands of smaller creditors and investors were ruined, included the in-laws of the painter Henri Matisse. But Therese and her family had already fled the country for Madrid. Panic erupted, and while the police of every capital in the world were looking for them, the Humberts blithely viewed the coronation ceremonies for King Alfonso. Late in December of that year, they were arrested in Madrid and brought back to Paris for trial.

The trial, immediately named L’Affaire Humbert, was just as absorbing and scandalous as that of the Dreyfus Affair which exposed the Anti-Semitism and treason raging in the French Army. It was revealed that the Bank of France loaned a sum never disclosed as it was able to stand the strain of failure, that Cattani, a banker, poured the trifling sum of 220,000 dollars into the Humbert coffins, that the Credit Industriel of Paris, handed out 120,000 dollars, and that victims included Empress Eugenie and the son of the president of the French Republic–-to say nothing of the scores of aristocrats, bourgeoisie, and working-class French citizens wiped out, or nearly so, by the swindle.

The trial lasted six weeks, and at its end, the judge passed the sentence of prison for 5 years for both Thérèse and Fredric, 3 years for Romain, and 2 for Emile, both of whom impersonated the fictional Crawford brothers in court. When Thérèse Humbert was released from prison, she emigrated to the United States where she died in Chicago in obscurity in 1918. The persons whom she had defrauded remained mostly silent to avoid further embarrassment, and the L’Affaire Humbert became a footnote in history.

Further Reading:

History’s Greatest Scandals by Ed Wright

The World’s Greatest True Crime by Colin Wilson

The Hypocrisy of Justice in the Belle Epoque by Benjamin F. Martin

La Grande Therese: The Greatest Scandal of the Century by Hilary Spurling