English cooking had a bad rap during the 19th and early 20th centuries. Caricatures of the typical Englishman (“John Bull”) poked fun at his florid face, his avoirdupois, and his bad manners when eating a meal consisting of a joint and boiled vegetables. In contrast, the typical Frenchman was even-complected, with a graceful figure, and impeccable and elegant table manners as he sat to dine at six course meal of the most aromatic and delicately prepared dishes. The mania for French cooking began with Antonin Carême, chef de cuisine to the Prince Regent, who simplified meals and organized dishes into distinct groups, and solidified under Alexis Soyer, whose feasts dominated the imaginations of the early Victorians. French haute cuisine reached its pinnacle beneath the magical fingers of Auguste Escoffier, who became one of the leaders in the development of modern French cuisine. Yet, beneath the canapés and ragoûts, traditional English cooking retained its position on the tables of not only the poor and working classes, but on the menus of aristocratic and royal houses.

English cooking had a bad rap during the 19th and early 20th centuries. Caricatures of the typical Englishman (“John Bull”) poked fun at his florid face, his avoirdupois, and his bad manners when eating a meal consisting of a joint and boiled vegetables. In contrast, the typical Frenchman was even-complected, with a graceful figure, and impeccable and elegant table manners as he sat to dine at six course meal of the most aromatic and delicately prepared dishes. The mania for French cooking began with Antonin Carême, chef de cuisine to the Prince Regent, who simplified meals and organized dishes into distinct groups, and solidified under Alexis Soyer, whose feasts dominated the imaginations of the early Victorians. French haute cuisine reached its pinnacle beneath the magical fingers of Auguste Escoffier, who became one of the leaders in the development of modern French cuisine. Yet, beneath the canapés and ragoûts, traditional English cooking retained its position on the tables of not only the poor and working classes, but on the menus of aristocratic and royal houses.

Traditional English cuisine was influenced by England’s Puritan roots, which shunned strong flavors and the complex sauces associated with European (Catholic) nations. Most dishes, such as bread and cheese, roasted and stewed meats, meat and game pies, boiled vegetables and broths, and freshwater and saltwater fish, had ancient origins, and recipes for the aforementioned existing in the Forme of Cury, a 14th century cook book dating from the royal court of Richard II. Not surprisingly, English cuisine had its regional dishes, the most famous being Cornwall’s Stargazy Pie, Derbyshire’s Bakewell tart, Lancanshire’s hot pot, Leicestershire’s Stilton cheese, and Devonshire’s clotted cream.

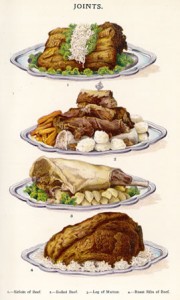

An Englishman was most proud of his meat and game, and even after dining à la russe surpassed service à la française in popularity, the host of a supper party considered carving a roast or a joint or a fish an art, and practically a divine right to show off at the table. In historical romances, the meat most often mentioned is mutton. Though meat in its various incarnations are typically described in an unappetizing manner, in truth, mutton is to lamb what beef to is veal–that is, meat from a sheep older than two years–and far from being cold and congealed and otherwise disgusting, mutton was very versatile; one could boil it, broil it, bake it, roast it, fillet it, stew it, braise it, and fry it.

An Englishman was most proud of his meat and game, and even after dining à la russe surpassed service à la française in popularity, the host of a supper party considered carving a roast or a joint or a fish an art, and practically a divine right to show off at the table. In historical romances, the meat most often mentioned is mutton. Though meat in its various incarnations are typically described in an unappetizing manner, in truth, mutton is to lamb what beef to is veal–that is, meat from a sheep older than two years–and far from being cold and congealed and otherwise disgusting, mutton was very versatile; one could boil it, broil it, bake it, roast it, fillet it, stew it, braise it, and fry it.

Due to game laws, other extremely popular meats such as venison, hare, partridge, pigeon, and pheasant, and so on, were restricted to the wealthy, since the land on which game (and the lakes and rivers where fish was found) were owned by English aristocrats or the Royal Family, and shooting and hunting permits were expensive. However, the Sunday roast, a traditional meal served on that day and consisting of “roasted meat, roast potato together with accompaniments, such as Yorkshire pudding, stuffing, vegetables and gravy,” was a meal common in all English households, with variations depending upon taste and budget.

Another most English dish is pudding. This is not the familiar milk-based chocolate or tapioca Jell-O brand seen in American supermarkets, but a rich, starchy, and typically savoury dish. Some puddings, such as rice pudding or Christmas pudding, were for dessert, but the best-known (Yorkshire pudding, suet pudding, blood pudding, etc) derived from English cooks devising ways in which to utilize fat drippings or leftover meats or blood.

During the British Raj, English cooks began to borrow from Indian dishes, creating a fusion cuisine known as “Anglo-Indian.” By the end of the 19th century, Kedgeree, Mulligatawny soup, curried meats, and chutney became such a staple on the English menu, the dishes were absorbed into the national English cuisine.

But let us not forget that most English of cuisine: Tea! Though tea was drunk in vast quantities by the English since the 17th century, it was when afternoon tea was devised by the Duchess of Bedford in the 1840s, that tea consumption increased. In 1911 alone, the people of the United Kingdom as a whole, consumed 296,000,000 pounds, or six and three-quarters pounds per person, of tea!!! Only Russia, which consumed 147,132,000 pounds of tea came close to that figure. Strangely enough, the French considered tea a medicinal drink, preferring coffee, though ardent Anglophiles gamely indulged in their “fif o’clock.”

Consumed with the tea were scones (Scottish in origin); dropped scones (which look like small pancakes) dipped in honey, crumpets (which look like English muffins); pikelets (“a British regional dialect word variously denoting a flatter variant on crumpet or muffin. In the West Midlands [and to some extent, the Yorkshire area] it is a term for crumpet. A crumpet in this area is similar in appearance [but not taste] to a North American pancake.”); light sandwiches (watercress, cucumber, ham, etc); and small cakes and pastries, all of which were displayed on tiered stands. Another form of tea was the “high tea,” which does not denote a fancy tea party, but a somewhat substantial meal of cold meats, tea, cakes, and sandwiches. This was mostly eaten by farming or working-class families, though, as the supper hour was pushed back to the late evening in the Edwardian era, English people of all classes tended to indulge.

And so, English cooking, despite its preponderance of heavy meats, savory delights, and brow-raising names (Toad-in-a-hole, anyone?), is far from deserving of its bad reputation. After all, many of our most famous English (and American) heroes and heroines dined daily upon these dishes and I feel secure knowing that Jane Austen, Anne Bronte, and Charles Dickens wrote their masterpieces nourished by their Mother Country’s cooking.

What a nice post! I’m hungry now!

Stargazy pie, though, can’t stand it, all those fishes staring at you. Love most of the other stuff, but I’m not one for blue cheese, Stilton especially (why eat mould? lol).

You can get cream teas in Devon and Cornwall, fresh scones, strawberry jam and clotted cream. With a nice pot of Yorkshire tea. In the US, I was at lunch with my then editor, Angela James, when the waiter asked me if I wanted my tea hot or cold. Angie said, “She’s English,” while I stared at him in disbelief!

Crumpets and muffins are very different. I have both in the kitchen.Crumpets have holes in them so you can drench them in butter. Muffins, also known as oven bottoms in my part of the world, are flattish bread buns. Soft, nice toasted or with cheese.

Best place for afternoon tea used to be Derry and Toms roof garden, on Kensington High Street. I always bypassed the cucumber sandwiches and went straight for the cakes!

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kensington_Roof_Gardens

Nowadays we have Delia, Heston and Gordon to teach us how to cook.

Scuse me, just wandering into the kitchen now…

Thanks for stopping by Lynne!

The story of you, Angela James, and the waiter, made me crack up! It’s one of the things I find funny about Anglo-American culture clashes. One of my missions is to host an English-style tea party for my friends; all I need now is a genuine tea kettle (can’t serve tea from water boiled in a coffee maker, now can I?).

Evangeline, come on over and look at my multiple posts about tea.

I love this article. It confirmed everything I knew instinctively 🙂

*

But one thought that had never occurred to me: that traditional English cuisine could be influenced by England’s Puritan roots, which shunned the strong flavours and the complex sauces associated with Catholic nations.

*

Absolutely. Catholic taste in paintings, architecture, music and every other thing became unacceptable to Protestant nations… why not food as well?

Yes, and it’s probably not a coincidence that French cuisine fell into favor during the 19th century, when Catholic nations (France, Spain, Holy Roman Empire/Austria-Hungary, etc) were in great turmoil, and Britain abolished laws barring Catholics from entering Parliament, and so on.

My mother’s family was English and that is reflected in my cooking. She was a world-class cook who could, and did, cook many cuisines (Her Chinese was unbelievably good), but she had the ability to make even humble, homey dishes like shepherd’s pie into something special. It’s a matter of cooking with care rather than slapping something together. (I had to draw the line, though, at steak and kidney pie. I still won’t eat organs!)