According to British restaurant critic, Giles Coren,”a hundred years ago, British food was in its golden age, with the arrival of the great restaurant, the celebrity chef, exotic new dishes, and gargantuan 12 course meals.” Leading the way was, of course, King Edward VII. When Prince of Wales, he had swept aside both the lengthy meal times, encouraged service à la russe, and introduced, via his great appetite, the trend for copious, rich, luxurious eating habits. By the time he came to the throne, “his aristocratic and upper middle-class subjects were set on an annual collision course with raging dyspepsia.”

The restaurant dinner, popular in Paris since the time of the French Revolution, had reached British shores by the 1880s. At first the act of dining in public was viewed warily–gentlemen were already accustomed to dining away from home at their clubs, men of the middle-class in steak shops and those of the working-class at oyster shops or food stands along the streets. For ladies, the thought of eating in a place where strangers could gawk and stare was abhorrent. The breaking down of social barriers contributed to the custom of “dining out” by the 1890s. No longer were private, in-home suppers indicative of who was “in” and who was “out”, and both ladies and gentlemen eagerly partook of the opportunity to leave their homes to see and be seen in the glamorous setting of a restaurant of the highest class.

To cater to this influx of diners, luxury hotels such as Claridge’s, the Cecil, the Ritz and the Savoy, began to remodel their dining rooms into chic restaurants, fitted with terraced dining, winter gardens and separate supper rooms for private parties. An American influence came with the introduction of the “bar” and the “grillroom”, which was a room set aside for informal dining. The advent of this new transatlantic society left one restaurant clinging to the English tradition of formal evening attire. To dine in the Savoy’s restaurant, or even to be served coffee in the adjoining foyer, it was absolutely essential that a lady wore a dinner gown sans chapeau and her escort a dress suit. Anyone who didn’t follow this command was liable to be refused entry, as an earl and his countess were to discover one night in 1907.

With these restaurants came the celebrity chef. Not since Antoine Carême ruled the stomachs of the Regency era’s celebrities had the British shores experienced the artistry of a chef de haute cuisine. His successor? Auguste Escoffier, a Nice-born chef who simplified and modernized Carême’s methods and contributed to the development of modern French cuisine. Forming a partnership with Cesar Ritz in 1890, the two men moved to the Savoy Hotel in London and from there, established numerous hotels, including the Hotel Ritz’s across the world. In 1898, they opened the Hotel Ritz in Paris, with The Carlton opening in London the following year, where Escoffier also introduced the practice of the à la carte menu.

Escoffier had a rival in the form of a woman: the former scullery maid and proud Cockney, Rosa Lewis. The proprietress of the Cavendish Hotel, she had begun her culinary career in the house of the Comte de Paris, the London-based Orleanist pretender to the French throne. From there she went from the kitchens of the Duc d’Aumale, to the Duc d’Orleans, and at one time, simultaneously controlled the kitchens of White’s Club, and W.W. Astor’s home, Hever Castle. It was when Lady Randolph Churchill acquired Rosa’s services that she began her ascent to fame. Anecdotes tell of the Prince of Wales, upon being introduced to Rosa by Lady Randolph as an excellent cook, never doubted it, exclaiming “Damme, she takes more pains with a cabbage than with a chicken. . . . She gives me nothing sloppy, nothing colored up to dribble on a man’s shirt-front.”

Rosa became the first freelance cook, and was available for hire by any person who could afford her services. With Bertie’s endorsement and her food witness to her talent, she became much in demand, with hostesses vying to obtain her services for country house parties throughout England. As she grew in importance, Rosa began to travel about with a chorus of assistant cooks attired exactly as she was, in spotless white with tall chef’s hats and high laced “cooking boots” of soft black kid, to support the ankles during the long hours spent preparing dishes.

During the Coronation year of 1902, Rosa produced 29 suppers for just as many large balls, and often came home in the wee hours of the morning without a wink of sleep. With the money saved from that year, she bought the Cavendish Hotel in Jermyn Street, where she earned a fortune catering to the vital needs of the aristocracy–privacy and excellent food. Available for use was a private dining room where swells could bring their lady friends, and permanent suites for those inclined to live outside of their homes.

Exotic dishes were created to meet the demand from aristocratic gourmands. The ultimate Edwardian recipe? A rich, extravagant dish comprised of pate de fois gras stuffed inside of a truffle, which was stuffed inside of an ortolan, itself stuffed inside of a quail. Escoffier invented the Peche Melba and Melba Toast in the 1890s, both dishes named for the strident soprano Nellie Melba, and Rosa Lewis invented a delicious quail pudding for King Edward.

Because meal times were pushed back by the close of the 19th century, other, smaller meals were inserted into the day to fill rumbling bellies. Lunch was inserted between breakfast and dinner, ladies added the afternoon tea. Another sort of tea–with hot muffins, crumpets, toast, cold salmon, pies, ham, roast beef, fruit, cream and tea and coffee–found its way into the more active and informal program of the country house.

The Edwardians never stopped eating. From the time they rose, to even the times they awoke in the middle of the night, food was ready and available. A typical English breakfast consisted of haddock, kidneys, kedgeree, porridge, game pie, tongue, poached eggs, bacon, chicken and woodcock. Luncheon included hot and cold dishes: cold fowls, lamb, pigeon, cold pie and ptarmigan, puddings, cheeses, biscuits, jellies, and fruit.

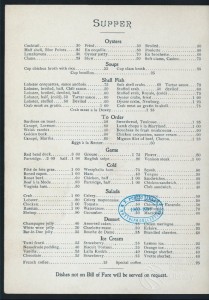

Supper now served à la russe, this allowed a greater sample of dishes available, and the course numbers grew. Guests sitting down for a ten to fifteen course meal was quite normal. Of course one wasn’t required to partake of each course, nor was it expected, but the parade of dishes: hors d’oeuvres, soups, salads, vegetables, meats–poultry, game, beef, mutton, and pork–, seafood, puddings, breads, savories, and fruits, if not the number of wines offered to compliment each course, was enough to make our 21st century stomachs queasy. And it didn’t end there. Hostesses expecting the King were well advised to provide snacks consisting of lobster salad and cold chicken to serve at eleven, and even after dinner, a plate of sandwiches, and sometimes a quail or cutlet, was sent to his rooms. At night, dainties were left outside of guests’ rooms during country house parties, in case someone felt a bit peckish.

Despite the expense put into creating these elaborate meals, those of smaller means weren’t left out of the general smörgåsbord. This was the apogee of name brands and modern processed foods such as Marmite (1902), Ty.phoo tea (1904), Colman’s Mustard (1903), bouillon cubes made simulate beef extract by Maggi (1908 ) and Oxo (1910), instant coffee (1901), Bird’s Custard Powder (est. 1837), Jacob’s water biscuits (1881), HP Sauce (1903) and Cadbury’s Milk Chocolate (est 1824). The appearance of refrigeration made dining much easier too.

This trend for gargantuan meals obviously had its downsides. A the end of the season, these Edwardian gastronomes found their digestion so wound in knots, a month-long jaunt to the Continent was deemed necessary. And the annual trek to Austrian or German watering spots like Bad-Ischl or Carlsbad, were added to the general round of the season. Here our ladies and gentlemen were put on strict diets and forced to exercise daily. At the end of the treatment, or “cure”, they would return to their homes a bit trimmer and with better digestion, only to begin the round of eating once more. Fortunately for the ladies, the standards of beauty praised the ample, womanly curves created by nature and enhanced with corsets, which gave them the signature “S” shape most assiduously admired by the men of the period.

Further Reading:

Manor House: Life in an Edwardian Country House by Juliet Gardiner

Rosa Lewis: An Exceptional Edwardian by Anthony Masters

Escoffier: The Complete Guide to the Art of Modern Cookery by H. L. Cracknell and R. J. Kaufmann

Food in History by Reay Tannahill

Comments are closed.