More than one’s residence, food and fashion greatly demarcates the wealth–or poverty–of the individual or family. During the Edwardian era, this was never more true, though, with the introduction of mass produced foods in America, those with less wealth could now afford to eat a bit more healthier.

More than one’s residence, food and fashion greatly demarcates the wealth–or poverty–of the individual or family. During the Edwardian era, this was never more true, though, with the introduction of mass produced foods in America, those with less wealth could now afford to eat a bit more healthier.

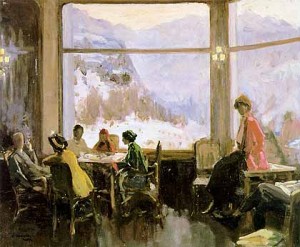

Starting at the top, the upper classes or aristocrats of this time divided their meals in a bevy of sections, and breakfast was split into two as well: formal or informal.

The formal breakfast differed slightly from an early luncheon, except that the menu made up of was distinctly breakfast dishes: Toast, hot muffins, omelets and other preparations of eggs, delicate farinaceous foods, cafe au lait, etc. A formal breakfast was held at any time between 10 and 12:30. A fruit course opened the menu: melons cut in slices, pink, green and yellow; baskets of “alert apples” and “self-conscious” peaches, with “sleepy grapes” hanging heavily over the rim. and plates of pears. This was followed by either a mild hors d’oeuvre or a dish of mush and cream, and then the breakfast plates were laid.

The coffee urn was filled, and a hot breakfast was served: beefsteak or lamb/veal chops, with a salad of sliced tomatoes or lettuce, with hard-boiled eggs, or poached eggs on toast; or omelet with muffins, or “pop-overs” with butter. Fish, broiled or saute, could also be served, and sometimes deviled lobster if it was preferred. In England, steamed finnan haddie was the favorite breakfast fish, and egg dishes wee always welcomed, accompanied with mushrooms, small French peas or potatoes. For the next course, chicken, broiled or fried with rice. Dessert of frozen punch, pastry or jellies followed; and coffee, in breakfast cups, concluded the meal. Hot muffins and crisp biscuits were made available, as were waffles and syrup.

An informal breakfast was less elaborate. It began with fruit, and may be followed by ham or bacon and eggs with johnny-cake and potatoes, or a simple breakfast may be started with cereal, served with cream, and followed by broiled finnan haddie and baked potatoes. Eggs, quail or chops, and a crisp salad was another menu often adapted to the late informal breakfast. Desserts were simple, as sweets were seldom indulged in at breakfast (buns with marmalade or honey; frozen puddings). This was given at 10 or 11 am.

Further on down the scale, the upper-middle- and middle-classes ate with more discretion. According to Mrs C.S. Peel, for a family of six or more persons, an average of a pound per head a week allows luxurious living; 15s. per head for good living; 10s. for simple living; and 8s. 6d. per head for sufficient living. An advised breakfast would include porridge, haddock, bacon and fried potatoes, brown loaf, toast, and honey; an omelet, crumpets, sardines, toast and preserves; cold tongue, apples; kippers, tongue toast, hot rolls; buttered eggs, potted meat, scones.

Further on down the scale, the upper-middle- and middle-classes ate with more discretion. According to Mrs C.S. Peel, for a family of six or more persons, an average of a pound per head a week allows luxurious living; 15s. per head for good living; 10s. for simple living; and 8s. 6d. per head for sufficient living. An advised breakfast would include porridge, haddock, bacon and fried potatoes, brown loaf, toast, and honey; an omelet, crumpets, sardines, toast and preserves; cold tongue, apples; kippers, tongue toast, hot rolls; buttered eggs, potted meat, scones.

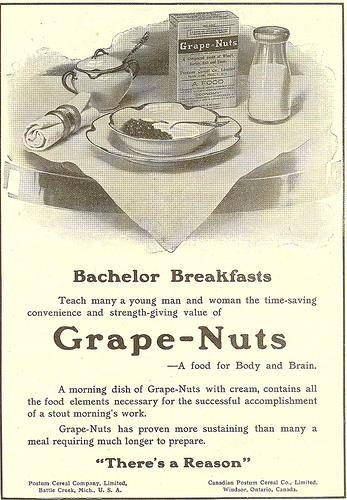

Menus in The Queen Cook-Book included fruit, cracked wheat, cream and sugar, broiled chicken, hashed potatoes, rolls, coffee; steamed hominy, scrambled eggs, lamp chops; oat meal, boiled eggs, beef steak. And an American cookbook entitled Cooking for Two, listed such items as an orange cut in half, bacon, broiled potatoes, radishes, toasted Boston brown bread, Grape Nuts and Cream, scrambled eggs, fried potato cakes, cream toast, lamb’s liver, creamed potatoes, buttered toast, marmalade, and coffee.

The meager menus eaten by the lower- and working-classes were detailed in heart-rending, but cold, hard facts in the multitude of exposes of London’s East End and other neighborhoods of poverty in Britain and America that flooded the bookstalls following the succès de scandale of Henry Mayhew’s London Labour and the London Poor. In it, he details the typical Street-Irish breakfast: a dish of potatoes, coffee and a slice of bread; herring, a cheap fish and potatoes; and two slices of bread-and-butter and a cup of tea for breakfast. Coffee stalls dotting the East End supplied a warm breakfast and “Rice-milk” girls, who tramped up and down the streets with urns of boiled rice, sold the white liquid with sugar, browned with allspice.

The meager menus eaten by the lower- and working-classes were detailed in heart-rending, but cold, hard facts in the multitude of exposes of London’s East End and other neighborhoods of poverty in Britain and America that flooded the bookstalls following the succès de scandale of Henry Mayhew’s London Labour and the London Poor. In it, he details the typical Street-Irish breakfast: a dish of potatoes, coffee and a slice of bread; herring, a cheap fish and potatoes; and two slices of bread-and-butter and a cup of tea for breakfast. Coffee stalls dotting the East End supplied a warm breakfast and “Rice-milk” girls, who tramped up and down the streets with urns of boiled rice, sold the white liquid with sugar, browned with allspice.

Tramps in London who lodged at the Casual Wards, told of their breakfast of one pint of gruel and 6 oz of bread, while English Poor Law policy stated that children were not to have tea or coffee, except for supper on Sunday, but milk and 2-3 oz of bread. Aged and infirm women and men however, got tea, coffee, or cocoa, with milk and sugar, accompanied by bread and butter or bread and cheese. A little more prosperous was the American working-class, who breakfasted on ham, sausage, biscuit, coffee, sugar, butter, syrup, and cheese.

Oddly enough, some of America’s enduring cereals were created in Sanatoriums. The first was Granula (named after granules), which was in 1863 by James Caleb Jackson, operator of the Jackson Sanatorium in Dansville, New York and a staunch vegetarian. However, the cereal never became popular; it was far too inconvenient, as the heavy bran nuggets needed soaking overnight before they were tender enough to eat. Fourteen years later, in Battle Creek Sanitarium in Battle Creek, Michigan, another cereal was invented. To alleviate the bowel problems of his patients, Dr. John Harvey Kellogg invented a biscuit of ground wheat, oat and cornmeal and named the product “Granula,” though he was forced to rename it “Granola” after a lawsuit. It was however, after he accidentally left a batch of boiled wheat soaking overnight and then rolling it out the next morning that Kellogg created wheat flakes. His brother Will Keith Kellogg, who later invented corn flakes from a similar method, bought out his brother’s share in their business, and went on to found the Kellogg Company in 1906. With his shrewd marketing and advertising, Kellogg’s sold their one millionth case after three years.

Oddly enough, some of America’s enduring cereals were created in Sanatoriums. The first was Granula (named after granules), which was in 1863 by James Caleb Jackson, operator of the Jackson Sanatorium in Dansville, New York and a staunch vegetarian. However, the cereal never became popular; it was far too inconvenient, as the heavy bran nuggets needed soaking overnight before they were tender enough to eat. Fourteen years later, in Battle Creek Sanitarium in Battle Creek, Michigan, another cereal was invented. To alleviate the bowel problems of his patients, Dr. John Harvey Kellogg invented a biscuit of ground wheat, oat and cornmeal and named the product “Granula,” though he was forced to rename it “Granola” after a lawsuit. It was however, after he accidentally left a batch of boiled wheat soaking overnight and then rolling it out the next morning that Kellogg created wheat flakes. His brother Will Keith Kellogg, who later invented corn flakes from a similar method, bought out his brother’s share in their business, and went on to found the Kellogg Company in 1906. With his shrewd marketing and advertising, Kellogg’s sold their one millionth case after three years.

In 1893, C.W. Post was a patient at the Battle Creek Sanitarium. After leaving, he began his own sanitarium, the La Vita Inn, and there developed his own coffee substitute, Postum in 1895. Two years later, Post invented Grape-Nuts, whose original formula called for grape sugar, which is composed mostly of glucose unlike most other sugar sources and food sweeteners which are principally sucrose. This, combined with the “nutty” flavor of the cereal inspired its name. Post immediately launched a nation-wide advertising campaign and quickly became a leader in the cereal business, with Post Toasties, a corn flake cereal to rival Kellogg’s following soon after.

Around this time, Cream of Wheat and shredded wheat cereal were invented. The former, a farina-based porridge, was invented in 1893 by wheat millers in Grand Forks, North Dakota and made its debut at the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago, while the latter was created by Henry Perky that same year, who founded The Natural Food Company based at Niagara Falls, NY in 1901. It became the Shredded Wheat Company in 1904.