The silhouette of the Edwardian woman changed drastically between the 1880s and the start of WWI. From the protruding bustle of the 1880s and the aggressive, slightly masculine leg-o’mutton sleeves of the 1890s, to the S-bend, swan-like shape of the 1900s and the ultra-slim line of the hobble-skirt in 1910, each reflected the shift of the roles women played in society. The “New Woman” of the 1890s was the natural reaction to the 1870s and 1880s, when not only were white-collar jobs increasingly available to them, but universities began to open their classes–or, in the case of Oxford and Cambridge–opened colleges for the education of women.

The silhouette of the Edwardian woman changed drastically between the 1880s and the start of WWI. From the protruding bustle of the 1880s and the aggressive, slightly masculine leg-o’mutton sleeves of the 1890s, to the S-bend, swan-like shape of the 1900s and the ultra-slim line of the hobble-skirt in 1910, each reflected the shift of the roles women played in society. The “New Woman” of the 1890s was the natural reaction to the 1870s and 1880s, when not only were white-collar jobs increasingly available to them, but universities began to open their classes–or, in the case of Oxford and Cambridge–opened colleges for the education of women.

The popularity of the bicycle, which enabled women much more freedom (and also brought about the grudging acceptance of the bloomer) from chaperonage and from past restrictions concerning their contact with places outside of the home. While ridiculous to modern eyes, the exaggeratedly puffed sleeves of the 1890s are said to be a metaphor for the aggressiveness of women, who played just as skillfully and competitively as their male counterparts in such sports as fencing, croquet, law tennis and hockey. To the older generation, the”New Woman,” who rode her bicycle to and fro, met single men for tea in the newfangled tea-rooms, attended college and–gasp–might have smoked (and all of it unchaperoned) was a shock to the systems–systems, for those who survived into the first decade of the 20th century, would suffer more shocks.

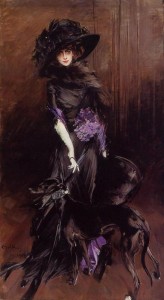

For a brief period at the turn of the century, fashions reverted to the overly feminine: pastel colors and the languid silhouette of the “S”-bend corset. Surprisingly, the S-bend corset (termed such, for it thrust the bosom forward and the derrière backward, causing the posture to bend) was invented by a female doctor as a health corset that fit beneath the bust and allowed for freer movement. Obstinate against their bodies being, in a sense, corset-less, women adapted this corset into its familiar usage. Starting around 1908, with the staggering width of hats, skirts began to narrow and the Directoire style arrived–an adaption of the empire waists and flowing skirts of the Regency era–, and corsets began to lengthen and straighten, starting just above the waist and fitting well down the thighs, thereby making sitting quite difficult.

For a brief period at the turn of the century, fashions reverted to the overly feminine: pastel colors and the languid silhouette of the “S”-bend corset. Surprisingly, the S-bend corset (termed such, for it thrust the bosom forward and the derrière backward, causing the posture to bend) was invented by a female doctor as a health corset that fit beneath the bust and allowed for freer movement. Obstinate against their bodies being, in a sense, corset-less, women adapted this corset into its familiar usage. Starting around 1908, with the staggering width of hats, skirts began to narrow and the Directoire style arrived–an adaption of the empire waists and flowing skirts of the Regency era–, and corsets began to lengthen and straighten, starting just above the waist and fitting well down the thighs, thereby making sitting quite difficult.

Ironically(or not), with the rising militancy of suffragists, skirts began to narrow until they became the barreled, banded style known as the hobble skirt. From 1911-1912, skirts became so narrow they hampered the movement of women, causing them a variety of problems that required the assistance of gentlemen for the most simplest of tasks. After that brief, brief period, hobble skirts began to feature discreet slits and panels, an accomodation which coincided with startling popularity of the Argentine tango. Hemlines also began their discreet rise, hitting the tops of boots by 1913, and rising eight inches from the ground by 1917. Oddly enough, despite the fabric shortages caused by WWI, skirts were wide and full during the war years, slimming down by 1918 and slowly morphing into the knee-skimming styles we identify with the 1920s.

variety of problems that required the assistance of gentlemen for the most simplest of tasks. After that brief, brief period, hobble skirts began to feature discreet slits and panels, an accomodation which coincided with startling popularity of the Argentine tango. Hemlines also began their discreet rise, hitting the tops of boots by 1913, and rising eight inches from the ground by 1917. Oddly enough, despite the fabric shortages caused by WWI, skirts were wide and full during the war years, slimming down by 1918 and slowly morphing into the knee-skimming styles we identify with the 1920s.

To dress the actual Edwardian lady was a daunting task in and of itself. “‘…. A large fraction of our time was spent in changing our clothes.” said Cynthia Asquith. From Lady Randolph Churchill to Consuelo Vanderbilt to Lady Diana Manners , copious memoirs written by the period’s luminaries all described this phenomenon. It wasn’t enough to keep up with the fashions, one had to carry them off with style and aplomb–and the quintessential Edwardian lady, tall, stately and beautiful, was the perfect canvas for the artistry of Worth, Doucet, Beer, Callot Soeurs, and Paquin.

A typical Saturday-to-Monday would require at least half a dozen changes of clothes: tweeds for shooting, habits for hunting, tea gowns for lounging, day dresses for day, evening gowns for supper, walking dress for promenading, and the requisite “tailor-made,” a suit of varying fabrics–depending on the occasion–, worn with shirtwaist, designed by the House of Redfern. Alongside these articles of clothing came sportswear, outerwear (mantelets, coats, jackets, pelisses), gloves, handbags, shoes, boots, parasols, brollies, and most importantly, hats.

The bonnet disappeared in the 1890s, and hats gradually grew wider as the era progressed, the “Merry Widow” hat of 1907-08 retaining its popularity until 1914. Onto these hats were piled masses and masses of flowers, netting, feathers, and sometimes, birds. It was not atypical for a lady to not have an elaborately-made hat with perhaps a stuffed pigeon–shot by her husband or an admirer–perched saucily between feathers. The craze for feathers got so bad, laws began to be passed restricting the use of certain types of bird’s feathers. All of this, besides hats, who were placed in hat boxes, would be packed into a trunk colloquially called a “Noah’s Ark.”

Articles of clothing themselves were as elaborate on the inside as they were without. Snaps and tapes fastened the blouse at either center back or the side and it was then hooked to the back of the skirt to combat gaping when the arms were lifted. These blouses, made of “soft clinging fabrics, with wilting sleeves dripping with expensive lace”, were elaborate and sometimes seductive confections of lace, ribbons and chiffon. The aptly titled “pneumonia blouse”, was a sheer, near transparent V-necked blouse that tantalized and hinted at the delicate skin hidden beneath. The skirts themselves were of languid and elegant gored lines, inspiring such names as “mermaid”, “eel” or “umbrella” skirt. Covering the blouse with a beaded and beribboned bolero jacket, sliding into slender Louis heels, and topping off with a wide hat, the Edwardian lady was dressed for the most simplest of that day’s tasks.

Articles of clothing themselves were as elaborate on the inside as they were without. Snaps and tapes fastened the blouse at either center back or the side and it was then hooked to the back of the skirt to combat gaping when the arms were lifted. These blouses, made of “soft clinging fabrics, with wilting sleeves dripping with expensive lace”, were elaborate and sometimes seductive confections of lace, ribbons and chiffon. The aptly titled “pneumonia blouse”, was a sheer, near transparent V-necked blouse that tantalized and hinted at the delicate skin hidden beneath. The skirts themselves were of languid and elegant gored lines, inspiring such names as “mermaid”, “eel” or “umbrella” skirt. Covering the blouse with a beaded and beribboned bolero jacket, sliding into slender Louis heels, and topping off with a wide hat, the Edwardian lady was dressed for the most simplest of that day’s tasks.

Further Reading:

Handbook of English costume in the nineteenth century by C. Willett Cunnington

Handbook of English Costume in the 20th Century 1900-1950 by Alan Mansfield and Phillis Cunnington

Victorian and Edwardian Fashions from “La Mode Illustree” by JoAnne Olian

A very interesting article!

Very interesting article. I’m learning so much from this blog in terms of researching my historical YA!

To Whom It May Concern,

I have in my possession some turn-of-the-century designer fashion catalogues (Edwardian era) that I find quite interesting. Maybe you can help me with rating their importance. Thank you.

#1) This is a hard cover “Haas Brothers, Blue Book of Models, Fall 1913. Paris (13 Rue des Pyramides) New York (303-305 Fifth Avenue)”: Approx. 146 page bound book. Black and White, in very good condition — and mostly intact. By that I mean my mom’s uncle used the first handful of pages as a boxing scrapbook, pasting over some of the illustrations. (The 1915 sports news clippings still remain.) Each fashion model is illustrated on a 10″x13.5″, glossy page, with brief text description of colors and materials used. Callot, Premet, Worth, Beer, Doucet, Cheruit, Evening, Drecoll, Bulloz, Robert, Georgette, Margaine, Paquin, Agnes, Bernard, Brandt, and Pasqual models.

#2) This is a group of four (4) “String-tied, folder type cover”, Hand-Colored Fashion Engravings Catalogues — 75(?) 10″x15″ individual illustrations, and in very good to excellent condition. From Morton Lasker, 339 Fifth Avenue, New York/Paris. Many of the same designers as above — and then some. And all pages suitable for framing.

In seasonal order:

a) L’AUTOMNE… 1914

b) PRINTEMPS… 1915

c) L’AUTOMNE… 1915

d) PRINTEMPS… 1916

So, there you have it. They are truly an interesting illustrated pictorial study of woman’s design and fashion. Every bit as interesting as what I’ve seen on other websites. What do you know? Thanks once again.

Dear Ray,

I was about to comment on the interesting article when I saw your list of fashion publications ~ I, too, have a Haas Brothers’ catalog, but mine is soft covered and has less pages, it’s from 1921, I think. I’ve never seen the Lasker catalogs, could you post or email me some pics?

Thanks!

Evangeline, bravo on the informative article! Loved the info on the “Merry Widow” hat and hobble skirts…My tastes run from that era through the flapper years, and I, like Ray, have a collection of prints, catalogs & magazines on those fashions. I hope to start posting about them in the upcoming year, will let you know.

Best regards to you both,

Susabella

Hi Susabella,

Thanks for stopping by! I look forward to your posts!