Trousers

During the last year men who ride have rather taken to check knickerbreeches. The material may be either what is called a Saxony or a Cheviot. The best colourings are black and white, black and grey, and brown and white.

The smartest of trouserings is a pure cashmere material. It is expensive but wears well, and if properly taken care of keeps its shape when made up until it is worn out. Some of these cashmeres are not unlike Bedford cords in appearance. Another good trousering is a mixture of cashmere and worsted. I don’t profess to know what advantage there may be in the mixture, but it is an excellent cloth for trousers, and rather stouter than the usual cashmere; in fact, ninety-nine men out of a hundred not in the trade couldn’t tell the difference between the two. Another very good trousering is a worsted. It is very like a cashmere, but not quite so fine. It is, however, quite as good for ordinary purposes. These worsteds are made very hard, so they keep their shape when worn, and the elastic weave of the material is a great advantage. Trousers made of this material soon regain their shape when put in the straighteners (see the chapter on Trousers).

Cashmere and worsted suitings similar in make to the cashmere and worsted trouserings, but stouter and with indistinct patterns instead of stripes, are always more or less fashionable. A mixed worsted suiting is also very serviceable, and most beautiful colourings and designs are worked out every year in this cloth. A very good suit to be worn at off-times in town can be made of this material. The plain worsteds are always more or less fashionable, but of late years there has been quite a rage for them, especially the plain grey. They are made up in frock coats, morning coats, or lounge suits. A good worsted will last as long as any material you can wear in town. A fine worsted is usually made up into summer overcoats, the favourite colour being drab or grey. This material looks very well when made into Raglan coats.

Plain serges are always more or less fashionable. Originally they were manufactured from one special very fine wool, but recently wool has gone up to such very high prices that serges are nearly always made of mixtures of different wools.

Tweed

The Donegal tweed does not seem to hold well together, and it is nothing like so good in any respect as the Harris tweed. The Harris tweed is really far and away the best material for a knickerbocker suit that you can possibly have. Most men have a sort of a vague idea that it is made by a man named Harris. This is quite wrong; the tweed is made in the Island of Harris and in parts of Scotland near it. It is woven from the pure wool of the sheep by the crofters; they get the wool and dye it themselves. Of course all their appliances and methods are very primitive, but the material comes out none the worse for that. All the dyes are composed of purely vegetable products, and are therefore perfectly “safe.” The genuine Harris tweed, being made from pure wool, is almost waterproof. If you are wearing a suit and it comes on to rain, you will find when you get home that you can shake nearly all the water off the coat.

I know that Harris tweeds have been objected to because of their patterns and colourings, which are rather loud. Well, what would you have in a suit that is intended for country wear? There is a kind of rough-and-ready look about the patterns which you cannot help liking when you get used to it, and there is this advantage about the Harris tweed—each pattern is distinct from the rest. You never get two patterns exactly alike. Some years ago you could always tell Harris tweed by the peculiar peaty smell attached to it, but within the last few years unscrupulous manufacturers have imitated Harris tweed to such an extent that they have even imitated this peculiar smell. I need scarcely say that the imitations are nothing like so good as the real thing.

Of course you cannot be expected to tell yourself what is Harris tweed and what isn’t. If you want to be absolutely certain of getting a suit length, you might write to Messrs. Paterson and Company, of Ingram Street, Glasgow. There is only one fault—if you can call it a fault—about the Harris tweeds, and that is, that they are apt to stretch out of shape, but this isn’t a serious matter with a knickerbocker suit. I have heard of men ordering Harris tweed trousers. Of course they (the trousers) looked very clumsy, and of course they went baggy at the knees at once. If you want a material that will last you, with fair wear, until you get absolutely tired of it, buy Harris tweed. I knew a man once who had a suit for eleven years, and then didn’t wear it out.

There are two great varieties of other tweeds—the Saxony and the Cheviot. The Saxony, being a finer material, hangs much better than the coarser and looser Cheviot. Saxony is always to be preferred to a Cheviot both for wear and appearance. Somehow or other, the Cheviot, being a coarser-looking material, is generally supposed to wear better than the Saxony, and so it is the most popular of all materials for general knock-about wear. But a Saxony is really the better of the two.

Suiting

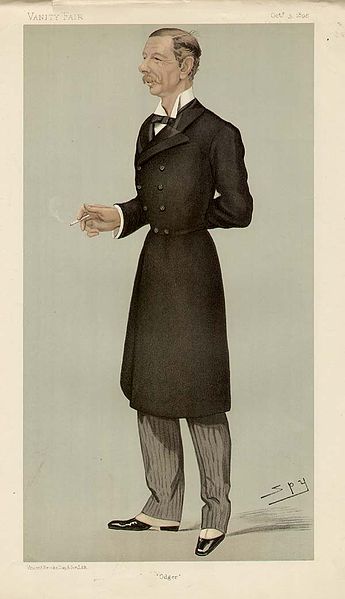

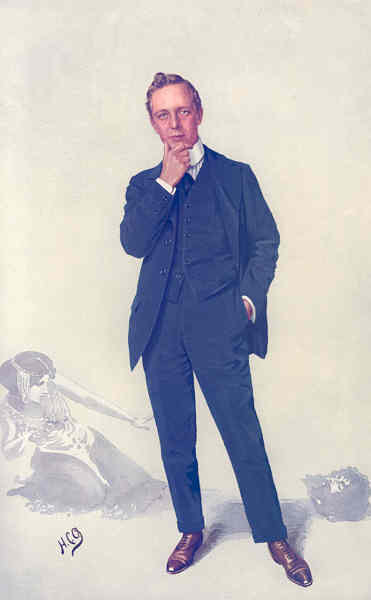

With regard to materials for black frock and morning coats, I have said already that the newest is a plain worsted, called by some tailors a diagonal cloth. This material soon wears shiny, but it wears “clean,” which is a great advantage. There is a smartness of finish about this cloth which recommends it to most men who like good clothes. The exact opposite to this kind of material is a soft llama woollen material. It is really a mixture of pure vicuna and llama, the pure llama being very expensive. It wears badly, picks up the dirt and dust, and although always more or less liked by men who are not obliged to be economical in the matter of clothes, it cannot be recommended for general wear. Plain vicuna, which is a cloth not quite so “woolly” as llama, has been very popular.

It wears well, does not soon go shiny, and its only disadvantage is that it catches the dust somewhat. In almost all black cloths you have to choose between one that wears shiny and one that picks up the dust. Perhaps the only coating in which these two disadvantages are not very apparent is the “West of England,” but it is not a cheap material. A good useful material is made of a mixture of vicuna and worsted. It is a sort of compromise between the glossy worsted and the dust-gathering plain vicuna. This is a good useful material for general purposes. A grey worsted coating mixed with vicuna is an excellent material for frock coats, morning coats, or lounge suits. It is made in all sorts of colourings and designs; there has been a great run on it for some years, and I have no doubt the run will continue for a good many more years to come. A mixture of serge and vicuna, a hard wearing cloth, will not wear shiny or catch the dust badly. It is used for morning coats and jackets.

One of the best materials for dress clothes is a worsted and vicuna mixture. You can also have a plain worsted and a plain vicuna, but the mixture is best. It wears clean and does not soon get glossy. The black material known as an elastic twill is always more or less in the fashion for dress clothes. What you have to remember when you are buying a dress suit is that the material must be jet black, very fine in texture, and not faced. The old-fashioned broadcloth has quite gone cut of fashion.

~ Clothes & The Man by Edward Spencer

Wonderful Artifact of a Bygone era.

Really fascinating! Can’t say I’ve ever fully appreciated the tough choice between dust-gathering or shiny-wearing fabric before.

My, what a to-do about black fabric. Btw, do you have any images of the patterns on Harris Tweed? They sound intriguing.

Yeah, really wonderful all those eras of wholesale men clothing.