Neatness and simple elegance should always characterize a lady, and after that she may be as expensive as she pleases, if only at the right time. And we may say here that simplicity and plainness characterize many a rich woman in a high place; and one can always tell a real lady from an imitation one by her style of dress. Vulgarity is readily seen even under a costly garment. There should be harmony and fitness, and suitability as to age and times and seasons. Every one can avoid vulgarity and slovenliness; and in these days, when the fashions travel by telegraph, one can be à la mode.

French women have a genius for dress. An old or a middle-aged woman understands how to make the best of herself in the assorting and harmonizing of colors; she never commits the mistake of making herself too youthful. In our country we often see an old woman bedizened like a Figurante, imagining that she shall gain the graces of youth by borrowing its garments. All this aping of youthful dress “multiplies the wrinkles of old age, and makes its decay more conspicuous.”

For balls in this country, elderly women are not expected to go in low neck unless they wish to, so that the chaperon can wear a dress such as she would wear at a dinner—either a velvet or brocade, cut in Pompadour shape, with a profusion of beautiful lace. All her ornaments should match in character, and she should be as unlike her charge as possible. The young girls look best in light gossamer material, in tulle, crêpe, or tarlatan, in pale light colors or in white, while an elderly, stout woman never looks so badly as in low-necked light-colored silks or satins. Young women look well in natural flowers; elderly women, in feathers and jewelled head-dresses.

If elderly women with full figure wear low-necked dresses, a lace shawl or scarf, or something of that sort, should be thrown over the neck; and the same advice might be given to thin and scrawny figures. A lady writes to us as to what dress should be worn at her child’s christening. We should advise a high-necked dark silk; it may be of as handsome material as she chooses, but it should be plain and neat in general effect. No woman should overdress in her own house; it is the worst taste. All dress should correspond to the spirit of the entertainment given.

Light-colored silks, sweeping trains, bonnets very gay and garnished with feathers, lace parasols, and light gloves, are fit for carriages at the races, but they are out of place for walking in the streets. They may do for a wedding reception, but they are not fit for a picnic or an excursion. Lawn parties, flower shows, and promenade concerts, should all be dressed for in a gay, bright fashion; and the costumes for these and for yachting purposes may be as effective and coquettish as possible; but for church, for readings, for a morning concert, for a walk, or a morning call on foot, a tailor-made costume, with plain, dark hat, is the most to be admired. Never wear a “dressy ” bonnet in the street.

The costumes for picnics, excursions, journeys, and the sea-side should be of a strong fabric, simple cut, and plain color. Things which will wash are better for our climate. Serge, tweed, and pique are the best. The trim tailor-made dresses and short skirts for bicycle riders leave nothing to be desired as to conciseness arid health, but are not often becoming.

A morning dress for a late breakfast may be as luxurious as one pleases. The modern fashion of imitation lace put on in great quantities over a foulard or a gingham, a muslin or a cotton, made up prettily, is suitable for women of all ages; but an old “company dress ” furbished up to do duty at a watering-place is terrible, and not to be endured.

It has been the fashion of late years to wear full dress at weddings. The groom at the same time wearing morning costume. It is an era of low necks for the young. The pendulum of fashion is swinging that way. We have spoken of this before, so only record the fact that the low neck will prevail in many summer evening house dresses as well as for morning weddings, the bride always wearing a high-necked dress.

The fashion of draping skirts tightly should make all women very careful as to the way they sit down. Some Frenchman said he could tell a gentleman by his walk; another has lately said that he can tell a lady by the way she sits down. A woman is allowed much less freedom of posture than a man. He may change his position as he likes, and loll or lounge, cross his legs, or even nurse his foot if he pleases; but a woman must have grace and dignity; in every gesture she must be “ladylike.” Any one who has seen a great actress like Modjeska sit down will know what an acquired grace it is.

A woman should remember that she “belongs to a sex which cannot afford to be grotesque.” There should never be rowdiness or carelessness.

The mania for extravagant dress on the stage, the pieces des robes, is said to be one of the greatest enemies of the legitimate drama. The leading lady must have a conspicuous display of elaborate gowns, the latest inventions of the modistes. In Paris these stage costumes set the fashions, and bonnets and caps and gowns become individualized by their names. They look very well on the wearers, but they look very badly on some elderly, plain, middle-aged, stout woman who has adopted them.

Plain satins and velvet, rich and dark brocades, made by an artist, make any one look well. The elderly woman should be able to move without effort or strain of any kind; a black silk well made is indispensable; and even ” a celebrity of a by-gone day “may be made to look handsome by a judicious but not too brilliant toilette.

The dress called “complimentary mourning,” which is rather a contradiction in terms, is now made very elegant and dressy. Black and white in all the changes, and black bugles and bead trimming, all the shades of lilac and of purple, are considered by the French as proper colors and trimmings in going out of black; while for full mourning the English still preserve the cap, weepers, and veil, the plain muslin collar and cuffs, the crape dress, large black silk cloak, crape bonnet and veil.

Heavy, ostentatious, and expensive habiliments are often worn in mourning, but they are not in the best taste. The plain-surfaced black silks are commendable.

For afternoon tea in this country the hostess generally wears a handsome high-necked gown, often a combination of stamped or brocaded velvet, satin, and silk. She sometimes wears what in England is called a “tea-gown,” which is a semi-loose garment. For visiting at afternoon teas no change is made from the ordinary walking dress, unless the three or four ladies who help receive come in handsome reception dresses. A skirt of light brocade with a dark velvet over-dress is very much worn at these receptions, and if made by a French artist is a beautiful dress. These dark velvets are usually made high, with a very rich lace ruff.

The high Medicean collar and pretty Medicean cap of velvet are in great favor with the middle-aged ladies of the present day, and are a very becoming style of dress for the opera. The present fashion of full dress at the opera, while it may not improve the music, certainly makes the house look very pretty and stately.

Too many dresses are a mistake, even for an opulent woman. They get out of fashion, and excepting for a girl going out to many balls they are entirely unnecessary. A girl who is dancing needs to be perpetually renewed, for she should be always fresh, and the “wear and tear” of the cotillon is enormous. There is nothing so poor as a dirty, faded, and patched-up ball-dress; the dancer had better stay at home than wear such.

The fashion of sleeves should be considered. A stout lady should wear, for a thin sleeve, black lace to the wrist, with bands of velvet running down, to diminish the size of the arm. All lace sleeves to the elbow, with drops of gold, or steel trimming, or jets, are very becoming to any arm.

Tight lacing is very unbecoming to those who usually adopt it—women of thirty-eight or forty, who are growing a little too stout. In thus trussing themselves up, they simply get an unbecoming redness of the face, and are not the handsome, comfortable-looking creatures which Heaven intended they should be. Two or three beautiful women, well-known in society, killed themselves by tight lacing. This has begun to attract the attention of physicians. The effect of an inch less waist was not apparent enough to make this a wise sacrifice of health and ease of breathing.

At a lady’s lunch party, which is always an occasion for handsome dress, and where bonnets are always worn, the faces of those who are too tightly dressed always show the strain by a most unbecoming flush; and as American rooms are always too warm, the suffering must be enormous.

It is a very foolish plan, also, to starve one’s self, or “bant” for a graceful thinness; women only grow wrinkled, show crow’s-feet under the eyes, and look less young than those who let themselves alone.

A gorgeously dressed woman in the proper place is a fine sight. A well-dressed woman is she who understands herself and her surroundings.

The recent edict of the Queen, that high dresses and long sleeves may be worn on a Presentation, will revolutionize costume in England. It, however, gives elderly and delicate women a great advantage, as only the marble skins look well on a cold English morning.

Tea-gowns are worn at receptions and afternoon teas, sometimes at small dinners in England and the United States, in 1900. They are very beautiful dresses, often of white satin trimmed with sable, and are most restful after a spin on the bicycle or the stiff habit required by horseback riding. They give a relief from the wearisome corset, and can be the most Oriental and charming things in the world.

The present fashion of white waists, or waists of a different color from the dress, is very cleanly, convenient, and economical, but singularly unbecoming to the average woman.

—Manners and Social Usages (1900)

The writer had a problem, since it was wrong to have

a] too many dresses

b] dresses that were theatrical, as an actress would wear

c] dresses with low necks

d] short skirts for bike riding etc etc etc.

Thank goodness there were some positive recommendations. “For afternoon tea in this country the hostess generally wears a handsome high-necked gown, often a combination of stamped or brocaded velvet, satin, and silk – the tea-gown.”

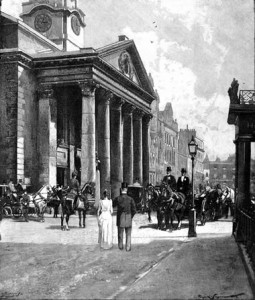

As your photo showed, the tea dress looked very elegant AND comfortable.

The picture says it all. No wonder so many readers love this period of time in their historical fiction. Of course, on a hot summer day one would curse all that draping and layering.