What would Society be without flirtation?

Almost all its arrangements are specially invented for the purpose of rendering flirtation easy and agreeable. The sitting-out corners at balls; the tops of coaches at Ascot or Sandown, or at Lord’s on the occasion of the Eton and Harrow match; the lazy, luxurious punt on the river; the dim recesses of the box at the opera; the tête-à-tête in the garden; the shelter on the grouse moor, shared by the sportsman and his lady friend,—one and all are purposely evolved for man’s delectation and woman’s amusement. American women are said to be the greatest flirts under the sun: they will “carry on” outrageously and publicly under Mrs. Grundy’s very nose, and then, when they have irritated a man to the pitch of insanity, they proceed to what they call “shake” him, or, in vulgar English, “chuck” him.

Flirtations used to be very sternly discouraged by mothers. Now, however, that the empire of parents is waning, and that they have laid the reins of government loosely on the daughters’ necks, young women generally aspire to having a good time. They get engaged at the end of a season——a condition which formerly meant the conclusion of young ladyhood, but now may be prolonged indefinitely, and which eventually may result in the freedom of both parties, the young people having changed their minds. Needless to say that flirtation under these circumstances can be pursued with admirable licence! The most unsophisticated girl learns something after an engagement of three months; and the void created when it has been broken off,——the want of adoration, of the hundred-and-one attentions and trifles that prove the ardour of a man——naturally impels her promptly to try her luck again as soon as ever she gets an opportunity, this time with a better chance of success.

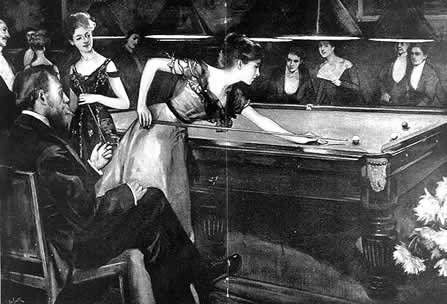

It has always been a mystery to me how our mothers and grandmothers, watched, escorted, and accompanied as they were, ever got wooed and married at all. At any rate, the modern girl would sorely resent any such galling system of chaperonage as formerly prevailed. She has so much liberty nowadays, and she appreciates it so well! There are thousands of opportunities in London for tête-à-têtes, and of these she avails herself freely. When her mother is present, she is probably in another room or at a safe distance; while the crowd and the difficulty of moving about render it impossible for the most watchful mother to know precisely where her daughter is, or with whom she has been dancing for the last hour. At Ascot or Sandown there is the rambling about in the paddock, nominally to look at the horses, in reality the better to carry on a flirtation; there is the long-drawn out luncheon in the Guards’ tent, where between strawberries and champagne much nonsense can be talked, and many loving glances given. In country houses there is the intimacy of billiards or lawn tennis, the rides in country lanes, or the gentle trot home from hunting. All sorts of surroundings suit all sorts of girls.

The London beauty is miserable out of the glare of wax candles and the hum of the city streets; her complexion does not stand early rising, and her feet are especially suited for dainty high-heeled shoes. Her appearance is regal in a ballroom, but she looks uncomfortable and dowdy when the rain has taken the curl out of her fringe, and with lank bits of hair falling over her forehead, with her best hat knocked out of shape, she sits under an umbrella in a Scotch picnic or at a meet of the hounds, disconsolate and weary; while her friend, a country girl who looks rosy and common and under-bred in London, appears charmingly neat and fresh in the studied simplicity of a tailor gown or the dainty adjuncts of a frilled, pink cotton skirt, or in the severe arrangement of a hunting habit.

She knows what sporting men like to talk about; she is up to the last racing tips; is well to the front in the big run, or can walk all day in the nattiest of short frocks with the shooters, and hails a good shot with veritable enthusiasm; while the town girl, who hates mud and wet and sporting “shop,” and the country (except just in July, when she can fly out of town every Saturday), sits silently by, completely out of her element. Flirtation in these two cases is founded on an entirely different basis. The daintiness, the languor, the indifference to everything and everybody carried to a ridiculous pitch in London society, becomes absolutely bad taste in the country: there it is better form to be bright and eager and undaunted in exertion.

Flirtations on the part of married women, too, are pretty frequent, and do not meet with the public disapprobation they provoked some years ago, and ought still to provoke. Whether husbands are more indifferent or more lax or more forgiving, the fact remains that pretty women do and say things constantly which pass the boundary of legitimate coquetry, which differ wholly and sadly from the interchange of compliment and smile that make the current coin of Society intercourse. To conclude: the essence of flirtation is froth; and those who look to find genuine sustenance in it will come away disappointed, for, as has been well said, “flirtation is a spoon with nothing in it.”

— The Gentlewoman in Society by Lady Violet Greville (1892)