Mourning customs in Edwardian England toned down the excesses of the high Victorian period, and the toll of World War One hastened the decline of the elaborate parade of mourning. Nevertheless, most held fast to traditional periods of mourning and their accompanying accoutrements, even as the scarcity of material and the costs of mourning garb and stationery rose considerably in the post-war era.

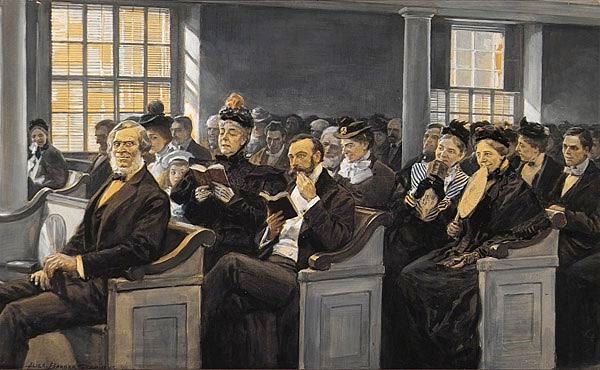

According to Mrs. C.E. Humphry (otherwise known as society columnist “Madge” of Truth): “When a death occurs in a family, the accepted mode of making the fact known to the outside world is by drawing down all the blinds and tying up the knocker with a piece of crape. An announcement of the death is sent to the papers for insertion in the obituary column, and letters are written to relatives and very intimate friends giving them the sad news.” Because women were thought to be in insufficient control of their emotions, the custom arose of forbidding their attendance at funerals. Though this “strict social law” gradually relaxed by the close of the 19th century, women mostly remained in the house until after the funeral service and burial had taken place.

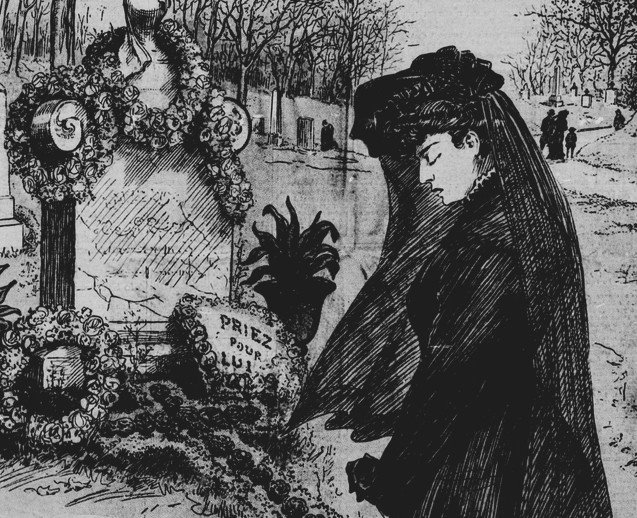

Accordingly, mourning customs for women were much more stringent than they were for men. Widows mourned their husbands for eighteen months to two years, whereupon they wore black dresses made of crepe, with “deep trimming of crape [sic] on the skirt” for the first twelve months. By 1913, widows wore crepe trimming only, and discontinued its wear after 6-8 months. The elaborate and stiff widow’s cap of the Victorian era had given way to the “graceful little Marie Stuart coif, with long ends at the back,” and ladies also had the option of wearing a crepe-trimmed bonnet with heavy veiling (this veil was exchanged for something lighter after two months). Jet was the only jewelry allowed, with “a watch chain, brooch, and ear-rings being the usual limit.” Diamonds and pearls were not permitted until crepe was taken off. Gloves were of black suede or wool.

Half-mourning was donned after a year and nine months, and was worn for three months. During this half-mourning, touches of white gradually appeared to a widow’s dress, and she exchanged her bonnet or cap and veil, for black chiffon toque. Gold jewelry was now permitted. By the end of the full mourning period, purples, greys, and deep mauves joined the black and white, thus signifying the gradual return to colors. During this time, the widow remained secluded from society for the first three months–she neither accepted nor issued invitations–and confined visits to family and intimate friends. After these three months, she gradually entered society, but balls and dances were strictly verboten for the first year.

Mrs. Humphry also mentions a brand new etiquette snafu of the Edwardian era: divorce and separation.

A woman who has divorced her husband would be guided by circumstances as to wearing mourning for him. Should he have married again and left a widow, it would be too absurd for two women to be wearing weeds for him; but if it should be thought advisable, in the interests of children, or for any other reason, for the woman who divorced him to wear mourning, she should do so, though without any exaggerated advertisement of regret. The children would wear mourning for their father, and it would be in singularly bad taste if their mother were not to don black and avoid colours until their period of mourning had expired. But a woman who has been divorced has no right to wear mourning for her former husband.

Women who are separated from their husbands have, in the same way, to be guided by a number of considerations as to whether they shall wear weeds or merely what is called “complimentary mourning ” on the death of the man. An incident that occurred to a lady may be related as showing how difficulties may arise when a couple are separated. She had been living abroad with one of her sons for some years, and meanwhile her husband had formed a temporary union in England with some one else. This latter lady died, and a notice of her death, as wife of Mr. So-and-so, appeared in a great daily paper.

The period of mourning for immediate relatives was less severe: six months in black, the first three with crepe; and three months half-mourning. Seclusion from society ranged from two to six weeks, depending upon the degree of the relationship. For example, a child mourning a parent or a parent mourning a child withdrew for six weeks and did not attend balls and dances for six months. When mourning a sibling, a grandparent, or an aunt or uncle, the period of seclusion was 2-3 weeks. For a daughter- or son-in-law, the mourning period was six months: four in black and two in half-mourning, or evenly split between to the two forms of dress.

In the 1860s and 1870s, men wore broadcloth suits and a tie of dull-surfaced silk for mourning, but by the 1900s, anything black signified mourning. A black hat-band was worn by men mourning various relations; widowers wore black for a year and usually entered society after three months.

Servants were provided mourning attire by their employers–and the men usually just wore black armbands–and they wore this for the same period as the family.

The First World War obviously changed these many of these customs, though society held on to these customs for as long as possible.

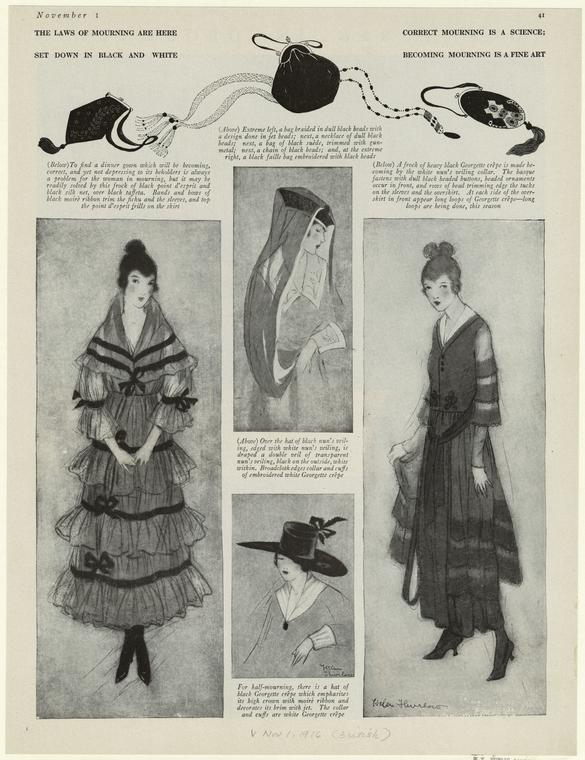

In the August 18, 1915 issue of The Sketch, fashion columnist Carmen of Cockayne considered the question of mourning “one of the most prominent dress problems of the day.” The suggestion of laying aside mourning to wear a white band around the arm was ignored, but it was recognized that “elaborate mourning is in the worst of bad taste, [and] a morbid exaggeration of dolour is equally so.” Widows’ mourning was reduced to eighteen months, with half-mourning for a few months more, and a small cap with small veil replaced the bonnet and widow’s cap. For dress, the first few months were spent in black cashmere with touches of white crape, and for the afternoon, dull black silks were permitted. Overall crepe was left to the widow’s personal taste. Periods of mourning morphed as well, with the mourning for a son lengthened to one year, and six months for a brother and three for a nephew. As with most advice for mourning during the war, the style, depth, and length of mourning was left to an individual’s taste and feeling rather than being standardized and regulated.

After the war, this streak of individuality intensified.

In the June 1922 issue of Vogue, the fashion writer remarked:

A generation ago there were absolutely strict rules for mourning, and in this respect no one who believed in the propriety of the conventions would have broken them. Today, every phase of life is being reexamined in the light of individual opinion, so that even mourning has become largely a question of personal feeling and the ultimate decision rests with the individual. However, there are still rules—or at least accepted conventions—for what is correct; and if one is going to break rules successfully, one must first know them thoroughly.

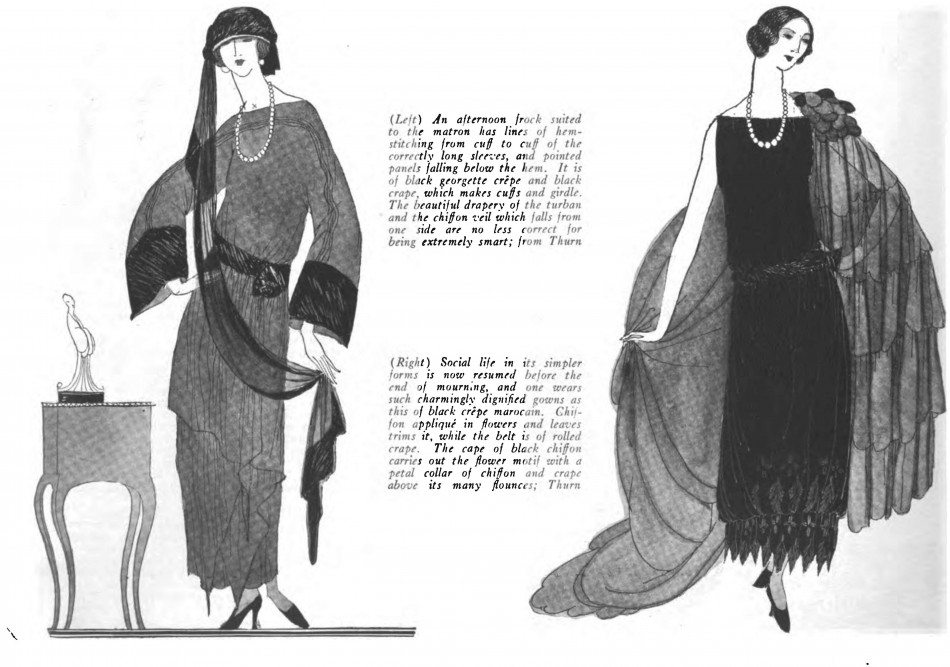

It is generally conceded that whatever the degree of mourning, all black should be worn for the funeral and for the first few weeks. After that time. the black may correctly be relieved with a small distribution of white. such as organdie collar and cuffs or a slight facing for the hat. All white is as strict mourning as the entirely black costume, but a more or less equal division of black and white, or grey and violet, is the accepted convention of second mourning.

One of the most marked changes in the etiquette of mourning is the decided abbreviation of the time that it is worn. The widow of twenty years ago wore the deepest mourning for two years. and half mourning for the rest of her life, if she did not remarry. To-day, the widow rarely wears the long crape veil for more than a year; some young widows, and even a few of the older matrons, now consider six months a sufficient period of deep mourning, but this is a very modern interpretation and is not the accepted convention. it has thus become customary for the widow. after the first year. to substitute a simple face veil, perhaps with a border of crape or chiffon or georgette crepe. It is not, however, considered correct for her to assume half mourning until after the end of the second year.

For a member of the immediate family, meaning a parent, a sister or brother, or a child, a year of deep mourning and a year of second mourning is the strictly correct usage. The crape veil worn in this case is somewhat shorter than the widows veil, and usage varies considerably as to the length of time for which it is worn. In strictly conventional mourning it is worn for six months, but the general tendency in mourning is to be less strictly conventional.

A small amount of jewellery is permitted by even the strict conventions of etiquette. The women who have fine pearls wear them although in the deepest mourning. However, even pearls must be discreetly used—for instance. a single string for the daytime or one beautiful rope in the evening. Also, a little black jewellery, such as onyx or jet set with diamonds. is smart and relieves the often dull appearance of the textiles.

There are two reasons for wearing mourning. The first is to show respect for the person who has died, and the second is for the protection of the person who is wearing it. Mourning may be smart, but it should not be conspicuous, and it may and should be becoming, for there is never a time when a woman is not right in seeking to look her best. Above all, it is important that the apparel of mourning should be always in good taste.

Sources

Etiquette for Every Day (1904) by Mrs. Humphry

Manners and Rules of Good Society (1913 & 1916 editions) by A Member of the Aristocracy

Etiquette of Good Society (1893) by Mrs. Colin Campbell

The Sketch (August 18, 1915)

Vogue (June 1922)

I didn’t know women weren’t supposed to attend funerals! That’s kind of mind-boggling.

They were too emotional, according to the dictates of the day. Can’t have a woman throwing herself on the coffin!

I remember in the late 60s in Scotland a relative of a friend died and no women attended the funeral.

Wow, interesting that the practice lingered.

That annoys me so much. Men wouldn’t allow their wives to work so wives were _totally_ dependent on the financial support of their husbands. Since men died first, on average, widowhood was both inevitable and a struggle for most women.

Of course mourning customs were more stringent for women 🙁 Life itself was more restrictive for women. I cannot even imagine how terrible WW1 must have been for most families.

Not only stringent, but expensive. Women had to change their entire wardrobe when in mourning, whereas men could get away with black suits.

When I was reading primary resources about WWI (diaries, letters, memoirs), I felt I was there, waiting for that telegram to come informing the family of their son or husband or brother’s death in action. Really heart-breaking.

Hi, Evangeline

I know that the blinds/curtains werre closed for mourning (my grandmother was still doing it in the 60s) but was this the case during WW1 as whole streets would have done so? Also can you suggest some diaries/letters/memoirs by women at home in England during WW1. I have read a number based on soldiers’ battlefield experiences but need to do some research on the women’s situation – particuarly where receipt of telegrams, mourning is concerned.

Thanks

One of the articles cited said the spelling of crape was incorrect. Its not. Crape was a crinkly fabric used specifically for mourning dress. Crepe is a modern crinkled paper.

Val

Both crape and crepe are used in fashion to describe the same fabric–in French it’s crêpe!

This is perfect. Edwardian mourning etiquette has been the subject of my research this week. Of course, I checked here first, and didn’t initially find a post. Am glad I checked again!

One question I’ve been unable to answer for myself (and perhaps you can point me towards the appropriate resource): would a matron go into mourning for a close female friend? Were there “official” rules for such mourning?

So glad my post was timely!

According to a dressmaker, mourning for a friend was mostly complimentary–4-6 weeks, and no crape.

Thank you for the response! That makes sense.

This was so interesting! As usual, your post had a wealth of information. I’ve been writing books set in Victorian London. No one has died yet, but I’ve bookmarked this post in case someone does, since you cover a lot of the traditions for mourning in that era, too. 🙂

🙂

I have a question about Lady Mary’s mourning dress in Season 4 of Downton Abbey. The season opens six months following her husband’s death and she is in black. When Lady Mary decides to join in with Tom Branson and her father in running the estate, she appears in a light purple and then a dark purple color. Wasn’t she rushing the color change from black to lighter purples rather quickly? Six months certainly wasn’t very long for deep mourning!

Downton took creative license with mourning, since we couldn’t spend an entire season with Mary in black! But, as the articles above said, the mourning was left to one’s own taste as opposed to the rigid etiquette of the Victorian era.

First of all, your posts have been a life-saver! I’m working on my first historical fiction story, and this website has been a godsend! =D So, you of all people will obviously know that tuberculosis was going around like the plague in the early 1900s, and it killed a lot of unfortunate people, leaving thousands in mourning. Obviously many of those would be widows. But there’s one thing that you didn’t touch on that I want to make clear: did they keep their married name after their husband’s untimely death, or did they revert to their maiden name? Because we know that women today have that option after their spouse passing or getting a divorce, but what about back then? Thanks so much! =D