Though I use the word “Edwardian” to encompass the same time frame on both sides of the Atlantic (with future jaunts to the Continent), and though the upper classes of America aped the aristocracy of Britain, there were some points where the etiquette of smart society diverged. I shall draw my examples from the 1900 edition of Manners and Social Usages by Mrs. John M. E. W. Sherwood (the United States), and the 1893 edition of Etiquette of Good Society by Lady Colin Campbell (Great Britain).

Letters

An elegant hand and proper salutation were key in both social sets, but Mrs. Sherwood lamented the death of letter writing due to telegrams, cheap postage, and postcards. The hustle and bustle of American life was present in the pre-printed address and initials dashed across the corner of the notepaper, and sometimes, the day of the week for shorter notes. Lady Colin Campbell cautioned against this practice, citing nosy servants and mail carriers. The trend for colored notepaper hung on in America, though the most fashionable color was écru, a creamy white. The most drastic difference between the two nation’s was the subject of sealing wax.

According to Mrs. Sherwood, sealing wax fell out of favor during the earliest voyages to California, where “the intense heat of the Isthmus of Panama melted the wax and letters were irretrievably glued together, to the lost of the address and the confusion of the postmaster. So the glued envelope–common, cheap, and necessary–became the almost prevailing fashion for all notes as well as letters. The use of wax is prohibited in correspondence with Cuba and the Philippines.” It is also interesting that Mrs. Sherwood emphasizes correct spelling, as George Cornwallis-West recalled the horrendous spelling of many of his peers in his memoirs, Edwardian Hey-Days (one particular correspondent asked to be remembered to his “yph”).

Dress

Both Mrs. Sherwood and Lady Colin Campbell praised the Frenchwoman as chicest, and wrung their hands over the innate gaudiness and gaucheness of American and English women. Dress for certain occasions were similar–plain, serviceable, and inconspicuous costumes for walking in the streets, delicate colors for lawn parties, fêtes, bazaars, etc; useful and sturdy clothing for picnics and excursions; and elegantly showy costumes for carriage rides. However, American ladies merely wore high-necked gowns at tea, whereas English women donned tea-gowns, and the more daring (such as Lady Randolph Churchill) wore kimonos. Mourning was once again a divergent point. As most of us know, English mourning customs were elaborate and rigid, though they grew less so in the 1900s. The Americans followed English fashions with the exceptions of heavy crepe and veiling, black gloves, thickly bordered notepaper, and “the hired mutes, the nodding plumes, the costly coffin, and the gifts of gloves and bands and rings, etc.”

Visiting

The concept of paying calls and leaving cards was quite difficult in America; “our cities have grown too large for it, and in our villages the population changes too quickly.” The original practice was to call once or twice a year on all one’s friends, with the hope of finding at least two or three at home. As society in cities such as New York grew, this became impossible, and the first solution was the establish a reception day which held good all winter. This was quickly abandoned and was narrowed down to four Tuesdays, perhaps in one month; that resolved itself into one or two five-o’clock teas. To circumvent the changes that would prohibit a woman from making calls or having reception days, one card a year was left at the door, or one sent in an enveloped, continued the acquaintance with new and old friends. Now contrast this rather lackadaisical approach with the strict etiquette of paying calls in England!

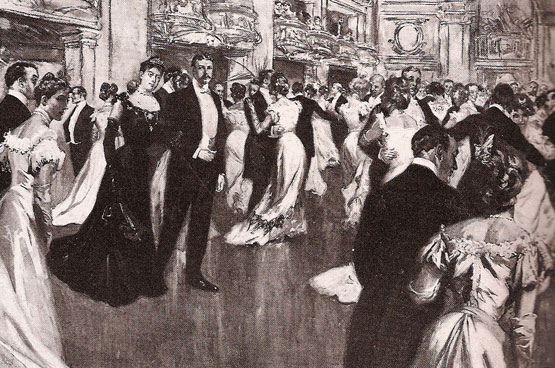

Balls

Dancing and balls were a major pastime in English society. According to Lady Colin Campbell, there were public balls–county balls, hunt balls, hospital balls, bachelors’ balls (or any ball to which a ticket was required)–, fancy dress balls (costume), and private balls, where the list of dances stretched from waltzes, lancers, galops, polkas, quadrilles, reels, country dances, and cotillions. Guests were ushered into cloakrooms when they arrived, where a maid was prepared to take cloaks, coats, hats, and wraps, and mend or repair any last-minute accidents to the toilet. They were then conducted to the tea-room, where tea, coffee, cakes, and biscuits were dispensed by a servant. After partaking of a cup or two, the guests are then shown into the drawing room, where the lady of the house received her guests.

Dancing began immediately, and it was considered the duty of family members to keep the guests happy (introducing strangers to one another, finding dance partners etc; the son of the house was supposed to dance with each lady). Refreshment rooms were also advised, where guests could drink claret, champagne, lemonade, sherry, and so on. In America, balls in the home fell out of fashion by the 1890s, and it was quite smart to host private balls in Sherry’s or Delmonico’s. When a ball was held in the home, guests merely greeted their hostess and circulated throughout the room before the dancing commenced. In both societies, a very good supper was provided. The “Cinderella Dance” rapidly came into favor with both American and English society. This dance was less elaborate and inexpensive, beginning at 8 pm and ending at midnight, and only claret, coffee, tea, and biscuits were provided.

Tea

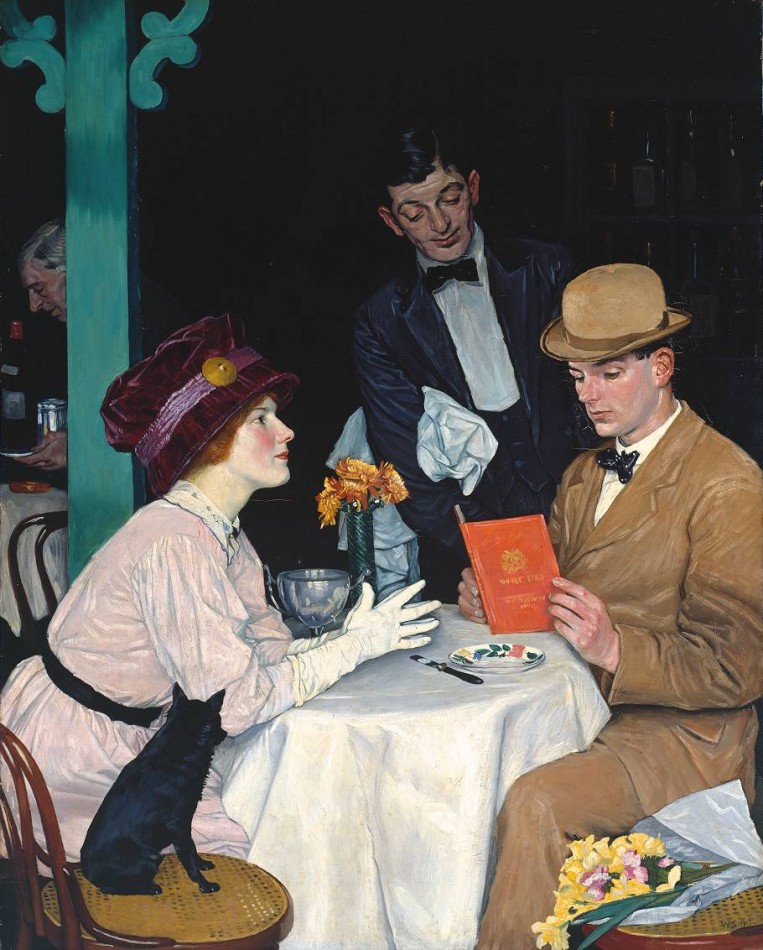

In England, there were two types of tea: “great teas” and “little teas”, with the “high” or “meat” teas coming under the former, and afternoon tea falling under the latter. High tea was largely a country institution, as the custom of late dinners during the London season interfered with the informality of country life. A “high tea” consisted of preserves, cakes of various times, hot muffins, crumpets, toast, and tea-cakes. A tray with the tea and its accoutrement were placed on one end of the table, and a tray with the coffee was placed on the other end. The sideboard held cold salmon, pigeon and veal and ham pies, boiled and roast fowls, tongues, ham, veal cake, and roast beef and lamb were there for the gentlemen of the party. In America, high tea took the place of dinner on Sunday evenings in cities, and were considered dinner in rural cities and the countryside. They were formerly fashionable in Philadelphia, where guests ate hot rolls and butter, escalloped oysters, fried chicken, cold ham, waffles, hot cakes, and preserves, and the hostess offered guests their choice of tea, coffee, or chocolate. Mrs. Sherwood doubted the popularity of high tea in America’s major cities, since “the custom of eight-o’clock dinners prevails.”

Afternoon tea was modified in England, since dinners were so late. It took place about five-o’clock, and the invitation was by card. The hostess poured the tea for her guests, and no plates were brought into the room except those large enough for cake or rolled bread and butter. Since the afternoon tea was an intimate affair, servants were usually dispensed with. The American hostess stood by her drawing room door to greet each guest, and in the adjoining room, usually the dining room, a large table was spread with a white cloth, and one end held the tea service, and the other, service for chocolate. Flowers adorned the table, and dishes containing bread and butter cut thin, and perhaps cake and strawberries were placed for consumption. Servants attended the tea to carry away soiled cups and saucers, and to keep the table looking fresh. In the summer, a bowl of cracked ice was included, for Americans loved iced tea!

English friends refer to “High Tea” as a slightly insulting term for the 4-6ish last meal of the day for “working class” people and small children…”Tea” is the posh little snack…with or without tea…”Dinner” is 8ish…

LOL, that’s funny, considering that (as referenced in the post), “High Tea” was dinner in provincial America of the 19th and early 20th centuries, but nowadays, it’s seen as an ultra-fancy tea time.

It was perfectly reasonable that different rules of etiquette would arise in very different societies. What might have been scary was if a person travelled, and was not aware that people did things differently Over There.

One tiny difference will demonstrate the point nicely. An American woman in a swish London dinner party cut her main course into tiny pieces and then put down her knife and transferred her fork to her right hand. The other guests went silent. Not a big deal but noone likes social gaffes, if they can help it.

Thank goodness for Sherwood’s and Campbell’s books!

I agree! After cook books, etiquette manuals are my favorite primary resource for understanding what was and what wasn’t considered proper behavior for people in the 19th and 20th centuries.

Evangeline, an etiquette writer myself, I always enjoy articles like this. And I’m always on the lookout for misuse of the term “high tea.” Glad to see this post making it clear that high tea is a meal. When I see tea establishments calling Afternoon Tea “high tea,” it bugs me!

Once I realized that misnomer, it bugs me too! Ah well, what was it Professor Higgins said about American English? *g*

You have to remember it evolved from the British and all the immigrants in the country. Roosevelt had an idea to streamline the language here and why the unnecessary U was removed from a lot of words like colour and color. The U is not needed and their are many others and when you use some of these words one has to remember some of them are actual place names which means writing something like Pearl Harbour is wrong. It is a place name and it is Pearl Harbor regardless of language. It is the same for other things. We are Americans and not English and our standards and etiquette and words for things are different just like in any country where the Queen doesn’t influence the language.

Dear Evangeline, I keep on reading (without a specific pattern) your blog. I had to smile at older societies and so-called social gaffes! Here on the West Coast of South Africa, next to the ocean, we are soooooo relaxed! Early coffee in bed, with rusks and biscuits and reading your blog, leads to a late brunch. On Sundays I bake fresh scones at 10. Neighbours and whoever is around “pops in” without formality, sometimes bringing an unusual preserve to add. The rest of the day we will need only one cooked meal at no specific time.

Once again your research is wonderful and you own amazing books and prints!

Thank you Marie! Your day sounds heavenly. 😉