I recently flipped through a research book dealing with Edwardian women and was struck by a passage referencing the brief and scandalous craze for nipple piercing which swept the ladies of the aristocracy during the late 1890s. Fortuitously, someone on the Victorian mailing list I am a member of posed a question about the validity of this trend. Research by other members led to an internet article in which two books are cited. Author Stephen Kern, in his book Anatomy and Destiny, writes that “‘bosom ring’ came into fashion briefly and sold in expensive Parisian jewelry shops. These ‘anneaux de sein’ were inserted through the nipple, and some women wore one on either side linked with a delicate chain.” In England, “a single Bond Street jeweler is supposed to have performed the nipple-boring operation on forty English ladies and young girls”, and the lady quoted above also confirmed the spread of this custom among the fashionable women of London. A certain Madame Beaumont performed the procedure in Paris, as a young woman and her sister, visiting the Paris Exhibition of 1889, shared:

I recently flipped through a research book dealing with Edwardian women and was struck by a passage referencing the brief and scandalous craze for nipple piercing which swept the ladies of the aristocracy during the late 1890s. Fortuitously, someone on the Victorian mailing list I am a member of posed a question about the validity of this trend. Research by other members led to an internet article in which two books are cited. Author Stephen Kern, in his book Anatomy and Destiny, writes that “‘bosom ring’ came into fashion briefly and sold in expensive Parisian jewelry shops. These ‘anneaux de sein’ were inserted through the nipple, and some women wore one on either side linked with a delicate chain.” In England, “a single Bond Street jeweler is supposed to have performed the nipple-boring operation on forty English ladies and young girls”, and the lady quoted above also confirmed the spread of this custom among the fashionable women of London. A certain Madame Beaumont performed the procedure in Paris, as a young woman and her sister, visiting the Paris Exhibition of 1889, shared:

“…a certain Madame Beaumont, who made the performance of the operation a part of her business. We obtained her address, and made an appointment to visit her. We found her occupying an elegantly-furnished apartment in a street leading from the Rue de Rivoli…Madame B’s business is to minister to the little wants and requirements of ladies, such as hair-dyeing, enamelling, corn doctoring, piercing their ears, and occasionally their nipples. She has quite an assortment of gold rings made expressly for this purpose, and she showed us that both herself and her daughter were at the time wearing them

…Madame B has invented an instrument for the purpose of insuring that the perforation is made in the proper direction through the nipple, and without any chance of failure. It is something like sugar tongs in form, but instead of spoons at the ends of the legs there is a pair of small tubes about 1 inch long, and in a straight line with each other, so that when the nipple is grasped between the inner ends of the tubes by means of a screw in the handle, a piercer can be passed through the whole without any chance of deviating from its proper course…

I partially undressed and seated myself on a couch by the side of Madame B, who passed her arm round my neck and held me steadily. Madame B then bathed my right breast for a few minutes with something which smelt like benzoline, and seemed almost to freeze it. She then adjusted the instrument to the niple, and screwed it up securely, and then, almost before I was aware of her insertion, she plunged the piercer through the tubes…

She then unscrewed and removed the tongs, leaving the piercer still sticking through the nipple, the point of the ring being then put into a hollow in the base of the piercer, the ring was passed through the nipple and closed…we spent the next few hours bathing our breasts with camphorated water, which Madame B had recommended us to use…after a time subsided we were able to dress and go about.“

In fact many ladies had small chains, instead of rings, fastened from breast to breast, and a celebrated actress of the Gaiety Theater wore “a pearl chain with a bow at each end.” Interestingly enough, these ladies pierced their nipples not only for its purported improvement to the bustline, but for the titillation factor, as acknowledged by a London modiste in a letter to a magazine:

“For a long time could not understand why I should consent to such a painful operation without sufficient reason. I soon, however, came to the conclusion that many ladies are ready to bear the passing pain for the sake of love. I found that the breasts of those who wore rings were incomparably rounder and fuller developed than those who did not. My doubts were now at an end…So I had my nipples pierced, and when the wounds healed, I had rings inserted…With regard to the experience of wearing these rings, I can only say that they are not in the least uncomfortable or painful. On the contrary, the slight rubbing and slipping of the rings causes in me an extremely titillating feeling, and all my colleagues to whom I have spoken on this subject have confirmed my opinion.”

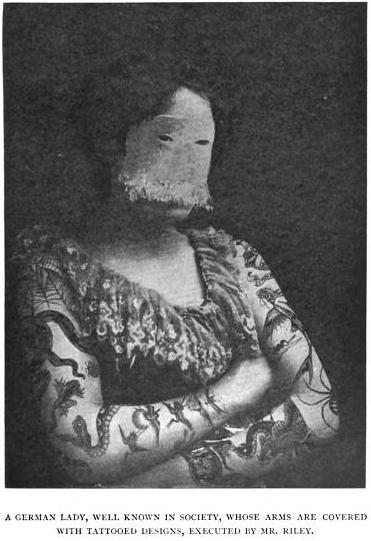

Another craze shared by both ladies and gentlemen alike during the Edwardian era were tattoos. Sparked by the Prince of Wales being inked on a visit to Jerusalem in 1862, the trend reached its height in the 1890s, when a foreign paper remarked upon the craze in “which even gentlemen are having done on the less exposed parts of their bodies” (Corriere della Sera, Milan, April 5, 1901).

Another craze shared by both ladies and gentlemen alike during the Edwardian era were tattoos. Sparked by the Prince of Wales being inked on a visit to Jerusalem in 1862, the trend reached its height in the 1890s, when a foreign paper remarked upon the craze in “which even gentlemen are having done on the less exposed parts of their bodies” (Corriere della Sera, Milan, April 5, 1901).

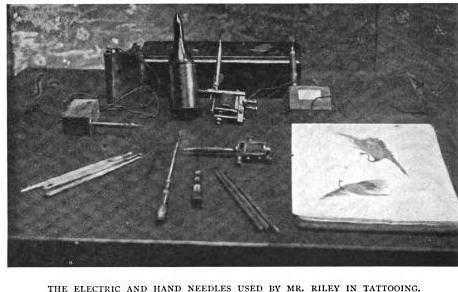

The go-to tattoo artist of the era was Mr. Tom Riley, who set up shop at the Earl’s Court Exhibitions, where he had quarters in the Western Arcades. In 1891, he and his American-based cousin S.F. O’Riley shared the patent on a tattoo needle. The needles worked like an electric bell and stylographic pen, and it was moved by a vibrating strip of metal in a similar way to the hammer of an electric bell. The needle itself worked up and down in a hollow spindle, from the end of which protruded every time the vibrating bar in the head of the machine moving up and down. The speed at which the vibrating bar moved was as nearly 1800 times a minute, so that the needle made about thirty distinct punctures in the skin every second. The hand needles used for “filling in” were made up of from two to eight to ten needles fastened together at the end of the a small wood or bone handle somewhat resembling a pen holder in size and shape.

The tattooing process was a set of five to six distinct operations as followed: “the preparation of the ‘canvas.’ Washing and shaving of the arm. The design selected on it with Indian ink and a very fine camel-hair brush, or transferred onto it by means of a drawing made with an aniline dye on tissue paper. The Paper is placed on the arm and damped all over a sponge: a towel is then tightly wound round the arm for a few seconds and when it and the paper and removed the design is left marked on the skin. When once the design is ‘fixed,’ whichever process is used, the work proceeds rapidly Selecting one of his machine needles and dipping the point in the slab of freshly-mixed Chinese ink, Mr. Riley commences the tattooing of the outline of the picture and as soon as this is done the principal dividing lines are worked in. next the small details are done.”

The tattooing process was a set of five to six distinct operations as followed: “the preparation of the ‘canvas.’ Washing and shaving of the arm. The design selected on it with Indian ink and a very fine camel-hair brush, or transferred onto it by means of a drawing made with an aniline dye on tissue paper. The Paper is placed on the arm and damped all over a sponge: a towel is then tightly wound round the arm for a few seconds and when it and the paper and removed the design is left marked on the skin. When once the design is ‘fixed,’ whichever process is used, the work proceeds rapidly Selecting one of his machine needles and dipping the point in the slab of freshly-mixed Chinese ink, Mr. Riley commences the tattooing of the outline of the picture and as soon as this is done the principal dividing lines are worked in. next the small details are done.”

Ladies had their lips and cheeks tattooed with color as well as regular tattoos. Accordingly, Lady Randolph Churchill (nee Jennie Jerome of Brooklyn, NY) was rumored to have a tattoo of a small snake winding around one of her wrists, and the scandalous Princess de Caraman-Chimay sported tattoos up and down both arms. Besides King Edward VII, known royalties with tattoos were the Duke of Saxe-Coburg, Prince George of Greece and Edward’s son, who reigned as George V.

Visit the Tattoo History Source, or read articles here and here for further information on Edwardian tattooing.

What magazine is the blockquote from? I assume it wasn’t the sort of thing one would find at WH Smith! 🙂

I had the quote for a while, but it wasn’t until I was browsing Google Books that I found its source: “The English Mechanic and World of Science”!

Interesting post. Anne Sebba however claims in her new biography that the story of Jennie Jerome Churchill having a tattoo was just a rumor, like the one that they had Iroquois Indian blood.

I did read that, but, who knows! All other media I’ve read which mentions Lady Randolph references a tattoo.