Richard Harding Davis, American adventurer, journalist, and prototype “Gibson man” (truly–he was the model!), was twenty-eight when he spent a term at Balliol College, but these excerpts from his letters home give a taste of the relatively leisured life of a privileged young man attending one of the top universities in the 1890s.

OXFORD–May, 1892.

DEAR FAMILY:

I came down here on Saturday morning with the Peels, who gave an enormous boating party and luncheon on a tiny little island. The day was beautiful with a warm brilliant sun, and the river was just as narrow and pretty as the head of the Squan river, and with old walls and college buildings added. We had the prettiest Mrs. Peel in our boat and Mrs. Joseph Chamberlain, who was Miss Endicott and who is very sweet and pretty. We raced the other punts and rowboats and soon, after much splashing and exertion, reached the head of the river. Then we went to, tea in New College and to see the sights of the different colleges now on the Thames. The barges of the colleges, painted different colors and gilded like circus band-wagons and decorated with coats of arms and flying great flags, lined the one shore for a quarter of a mile and were covered by girls in pretty frocks and under-grads in blazers.

Then the boats came into sight one after another with the men running alongside on the towpath. This was one of the most remarkable sights of the country so far. There were over six hundred men coming six abreast, falling and stumbling and pushing, shouting and firing pistols. It sounded like a cavalry charge and the line seemed endless. The whole thing was most theatrical and effective. Then we went to the annual dinner of the Palmerston Club, where I made a speech which was, as there is no one else to tell you, well received, “being frequently interrupted with applause,” from both the diners and the ladies in the gallery. It was about Free Trade and the way America was misrepresented in the English papers, and composed of funny stories which had nothing to do with the speech. I did not know I was going to speak until I got there, and considering the fact, as Wilson says, that your uncle was playing on a strange table with a crooked cue he did very well.

The next morning we breakfasted with the Bursar of Trinity and had luncheon with the Viscount St. Cyres to meet Lord and Lady Coleridge. St. Cyres is very shy and well-bred, and we would have had a good time had not the M. P.’s present been filled with awe of the Lord Chief Justice and failed to draw him out. As it was he told some very funny stories; then we went to tea with Hubert Howard, in whose rooms I live and am now writing, and met some stupid English women and shy girls. Then we dined with the dons at New College, so–called because it is eight hundred years old. We sat at a high table in a big hall hung with pictures and lit by candles. The under-grads sat beneath in gowns and rattled pewter mugs. We all wore evening dress and those that had them red and white fur collars. After dinner we left the room according to some process of selection, carrying our napkins with us. We entered a room called the Commons, where we drank wines and ate nuts and raisins. It was all very solemn and dull and very dignified.

Outside it was quite light although nine o’clock. Then we marched to another room where there were cigars and brandy and soda, but Arthur Pollen and I had to go and take coffee with the Master of Balliol, the only individual of whom Pollen stands in the least awe. He was a dear old man who said, “O yes, you’re from India,” and on my saying “No, from America”; he said, “O yes, it’s the other one.” I found the other one was an Indian princess in a cashmere cloak and diamonds, who looked so proud and lovely and beautiful that I wanted to take her out to one of the seats in the quadrangle and let her weep on my shoulder. How she lives among these cold people I cannot understand. We were all to go to a concert in the chapel, and half of the party started off, but the Master’s wife said, “Oh, I am sure the Master expects them to wait for him in the hall. It is always done.” At which all the women made fluttering remarks of sympathy and the men raced off to bring the others back. Only the Indian girl and I remained undisturbed and puzzled.

The party came back, but the Master saw them and said, “Well, it does not matter, but it is generally done.” At which we all felt guilty. When we got to the chapel everybody stood up until the Master’s party sat down, but as it was broken in the middle of the procession, they sat down, and then, seeing we had not all passed, got up again, so that I felt like saying, “As you were, men,” as they do out West in the barracks. Then Lord Coleridge in taking off his overcoat took off his undercoat, too, and stood unconscious of the fact before the whole of Oxford. The faces of the audience which packed the place were something wonderful to see; their desire to laugh at a tall, red-faced man who looks like a bucolic Bill Nye struggling into his coat, and then horror at seeing the Chief Justice in his shirt-sleeves, was a terrible effort–and no one would help him, on the principle, I suppose, that the Queen of Spain has no legs. He would have been struggling yet if I had not, after watching him and Lady Coleridge struggling with him, for a full minute, taken his coat and firmly pulled the old gentleman into it, at which he turned his head and winked.

I will go back to town by the first to see the Derby and will get into lodgings there. I AM HAVING A VERY GOOD TIME AND AM VERY WELL. The place is as beautiful as one expects and yet all the time startling one with its beauty.

DICK.

~ Adventures and letters of Richard Harding Davis

Davis later culled from his experiences at Oxford to write an article for Harpers Weekly:

The day of an Oxford man is somewhat different from that of an American student. He rises at eight, and goes to chapel, and from chapel to breakfast in his own room, where he gets a most substantial breakfast—I never saw such substantial breakfasts anywhere else — or, what is more likely, he breakfasts with some one else in some one else’s rooms. This is a most excellent and hospitable habit, and prevails generally. So far as I could see, no one ever lunched or dined or breakfasted alone. He either was engaged somewhere else or was giving a party of his own. And it frequently happened that after we were all seated our host would remember that he should be lunching with another man, and we would all march over to the other man’s rooms and be received as a matter of course. It was as if they dreaded being left alone with their thoughts. It struck me as a university for the cultivation of hospitality before anything else.

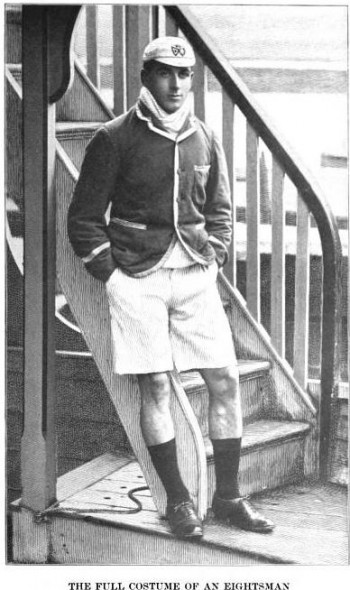

After breakfast the undergraduate “reads” a bit, and then lunches with another man, and reads a little more, and then goes out on the river or to the cricket-field until dinner. The weather permits this out-of-door life all the year round, which is a blessing the Oxford man enjoys and which his snow-bound American cousin does not. His dinner is at seven, and if in hall it is a very picturesque meal. The big hall is rich with stained glass and full-length portraits of celebrated men whose names the students never by any possible chance know, and there are wooden carved wainscotings and heavy rafters. There is a platform at one end on which sit the dons, and below at deal tables are the undergraduates in their gowns—worn decorously on both shoulders now, and not swinging from only one—and at one corner by themselves the men who are training for the races. The twilight is so late that the place needs only candles, and there is a great rattle of silver mugs that bear the college arms, and clatter of tongues, and you have your choice of the college ale or the toast and water of which you used to read and at which you probably wondered in Tom Brown at Oxford. The dons are the first to leave, and file out in a solemn procession. If you dine with the dons and sit above your fellow-men you are given the same excellent and solid dinner and wine in place of beer, and your friends of the morning make faces at you for deserting them and because of your higher estate,

My first dinner with the dons was somewhat confusing. After a most excellent service somebody rose, and I started with the rest down the steps towards the door, when my host stopped me and said, “You have forgotten to bring your napkin.” What solemn rite this foretold I could not guess. I had enjoyed my dinner, and I wanted to smoke, and why I needed a napkin, unless as a souvenir, I could not see; and I continued wondering as we marched in some certain order of precedence up and down stone stairways and through gloomy passages to another room in an entirely different part of the college, where we found another long table spread as carefully as the one in the hall below with many different wines and fruits and sweets. And we all sat down at this table as before, and sipped port and passed things around and talked learnedly, as dons should, for half an hour, when we rose, and I again bade my host good-night, but he again stopped me with a deprecatory smile, and again we formed a procession and marched solemnly through passages and over stone floors to another room, where a third table was spread, with more bottles, coffee, and things to smoke. It struck me that an Oxford don mixes some high living with his high thinking. I did not wait to see if there were any more tables hidden around the building, but I suppose there were.

After dinner the undergraduate reads with his tutor out of college or in his own rooms. He cannot leave the college after a certain early hour, and if he should stay out all night the consequences would be awful. This is, of course, quite as incomprehensible to an American as are the jagged iron spikes and broken glass which top the college walls. It seems a sorry way to treat the sons of gentlemen, and more fitted to the wants of a reformatory. There is one gate at Trinity which is only open for royalty, and which was considered to be insurmountable by even the most venturesome undergraduate, until one youth scaled it successfully, only to be caught out of bounds. The college authorities had no choice in the matter but to send him down, as they call suspending a man in Oxford; but so great was their curiosity and belief in the virtue of the gate that they agreed to limit his term of punishment if he would show them how he scaled it. To this, of course, he naturally agreed, and the undergraduates were edified by the sight of one of their number performing a gymnastic feat of rare daring on the top of the sacred .iron gate, while the college dignitaries stood gazing at him in breathless admiration from below.

~ Our English Cousins

This sounds very ordered and civilized compared to accounts from American university students in the late 19th century!