Until the emergence of the waltz in the early 19th century, the minuet reigned supreme as the courtliest, most aristocratic of dances. It was stately, it was elegant, it was—most importantly—proper; only the hands of the dance partners touched, their fingers clasped ever so gently. When the Viennese waltz set a dainty foot on English ballrooms, it shock the church and society with the prolonged bodily contact not just of the hands, but of the body! The dance was quickly denounced by the Anglican archbishops as a lust-inducing, decidedly degenerate action to be left to those hot-blooded, silly foreigners. Needless to say, the more forbidden the dance became the more anxious society was to engage in it—while at the same time considering it scandalous. However, by 1816, the dance had finally reached respectability and the waltz firmly fastened itself onto the dance schedules of balls and routs of English society for the majority of the 19th century. Society thought itself safe from unruly and scandalous dances, having only added the polka in the 1840s, the Virginia reel, germans, and other vigorous dances which did no more harm than red faces and shortness of breath.

Until the emergence of the waltz in the early 19th century, the minuet reigned supreme as the courtliest, most aristocratic of dances. It was stately, it was elegant, it was—most importantly—proper; only the hands of the dance partners touched, their fingers clasped ever so gently. When the Viennese waltz set a dainty foot on English ballrooms, it shock the church and society with the prolonged bodily contact not just of the hands, but of the body! The dance was quickly denounced by the Anglican archbishops as a lust-inducing, decidedly degenerate action to be left to those hot-blooded, silly foreigners. Needless to say, the more forbidden the dance became the more anxious society was to engage in it—while at the same time considering it scandalous. However, by 1816, the dance had finally reached respectability and the waltz firmly fastened itself onto the dance schedules of balls and routs of English society for the majority of the 19th century. Society thought itself safe from unruly and scandalous dances, having only added the polka in the 1840s, the Virginia reel, germans, and other vigorous dances which did no more harm than red faces and shortness of breath.

Then came ragtime.

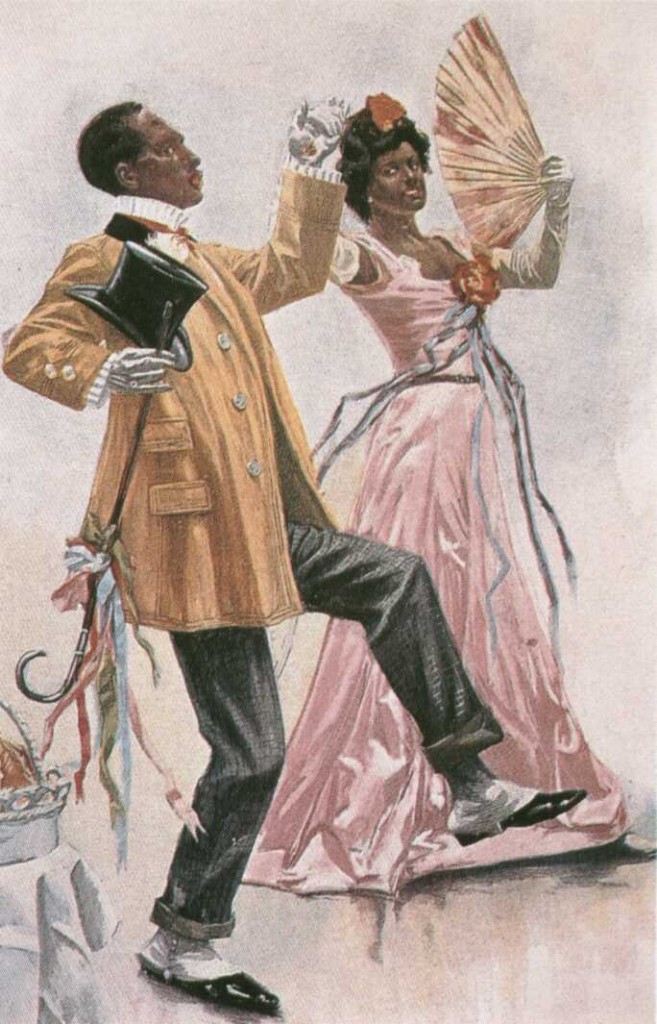

By the turn of the century, the syncopated rhythms of African-Americans had slowly but surely invaded the sedate ballrooms of American society. Composers like Scott Joplin, whose Maple Leaf Ragtime made him the first mainstream black artist in American history, created a furor for ragtime and the phonograph. By the time Irving Berlin became an overnight sensation with Alexander’s Ragtime Band and Everybody’s Doin’ It Now, ragtime music had inspired dances with amusing names like the Turkey Trot, the Grizzly Bear, and the Bunny-Hug. Moralists, parents, and statesmen from America to Russia decried the corrupting influence of these dances on youths, but they only served to make them even more popular. However, nothing prepared the terrified older generation for the tango.

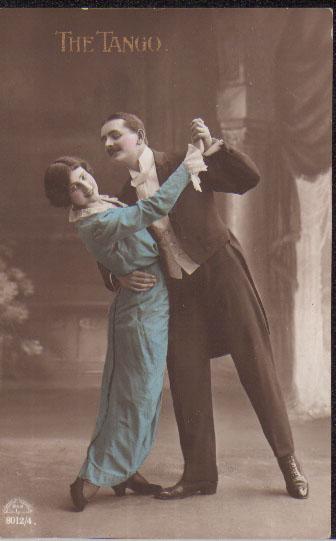

This slinky, sensual dance emerged from the fusion of Afro-Latin-American rhythms and movements. It was said the dance originated from the brothels of Argentina, where they were danced by the lower classes and prostitutes of both sexes. Upon the migration of Argentinians to Europe, the dance hit mainstream first in Paris, around 1910, making its way to England and the US by 1913. In reaction to the fluid movements of the tango, skirts suddenly slit to the knee, people began to talk of gigolos, “Tango teas” became the craze, and Latin American music began to supersede the graceful Viennese melodies of the nineteenth century.

This slinky, sensual dance emerged from the fusion of Afro-Latin-American rhythms and movements. It was said the dance originated from the brothels of Argentina, where they were danced by the lower classes and prostitutes of both sexes. Upon the migration of Argentinians to Europe, the dance hit mainstream first in Paris, around 1910, making its way to England and the US by 1913. In reaction to the fluid movements of the tango, skirts suddenly slit to the knee, people began to talk of gigolos, “Tango teas” became the craze, and Latin American music began to supersede the graceful Viennese melodies of the nineteenth century.

And history repeated itself once again with the vitriolic protest Pope Pius X launched against the tango. In Milan, priests thundered from the pulpits, warning congregations “not to indulge in the immoral dance; better still not even to watch it for fear of temptation.” But as with the waltz, Society turned a deaf ear to the remonstrations and in fact, took to the tango (and those wild ragtime dances) with even more alacrity than with the waltz.

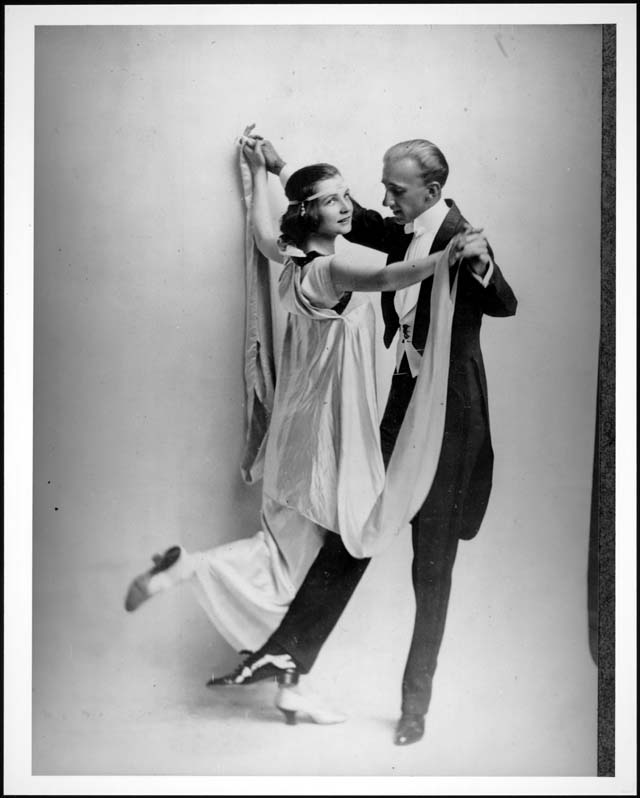

For many, despite the insistence that in order to be fashionable, one must do the dances, the tangos and Boston two-steps and such were too much for their sensibilities. Into the fray leaped an American couple by the names of Irene and Vernon Castle. After a stint in Paris, the Castles introduced sedate versions of the raucous dances into the parlors of America’s aristocracy. They placed a firm emphasis on the health benefits and gracefulness of dancing, and as a result of their performances on Broadway, garnered the patronage of thankful matrons such as Mrs. Stuyvesant Fish and Mrs. Rhinelander. The highly-successful couple made the first dance instruction video (1909) and wrote a number of popular books on dancing. To date, a number of films have been made about them, most especially a movie featuring Fred Astaire and Ginger Rogers.

For many, despite the insistence that in order to be fashionable, one must do the dances, the tangos and Boston two-steps and such were too much for their sensibilities. Into the fray leaped an American couple by the names of Irene and Vernon Castle. After a stint in Paris, the Castles introduced sedate versions of the raucous dances into the parlors of America’s aristocracy. They placed a firm emphasis on the health benefits and gracefulness of dancing, and as a result of their performances on Broadway, garnered the patronage of thankful matrons such as Mrs. Stuyvesant Fish and Mrs. Rhinelander. The highly-successful couple made the first dance instruction video (1909) and wrote a number of popular books on dancing. To date, a number of films have been made about them, most especially a movie featuring Fred Astaire and Ginger Rogers.

These days, dances that scandalized our ancestors are consigned as relics of the past, considered “fusty” and “fussy”, only seen in old musicals or costume movies, and sometimes at ballroom dancing competitions. Except the tango. To today, it continues to be seen as a sensual, decidedly un-fusty dance of seduction. For more information on these dances and others, visit Street Swing!

Further Reading:

Vernon and Irene Castle’s Ragtime Revolution by Eve Golden

The Golden Age of Tango: An Illustrated Compendium of Its History by Horacio Ferrer

This Is Ragtime by Terry Waldo

Dance, A Very Social History by Carol McD. Wallace

we don’t know how to dance properly- as couple -in two, today, even if some people dance on blues but they are not trained to dance, they don’t know the moves, today it is preferred solo,and as society as well, it is advisable independence of a person rather than dance as a couple