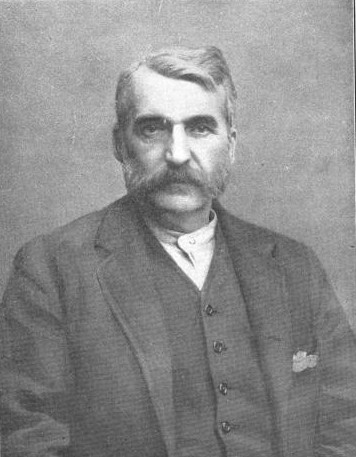

For a large part of the late 19th century, one man confounded, outwitted, and bemused the police forces of multiple continents: Adam Worth (1844-1902). So difficult was it to catch him red-handed, so wily were his swindles, and so brazen were his thefts that Scotland Yard called him the “Napoleon of Crime.” His greatest and most famous theft of all was that of Gainsborough’s portrait of Georgiana, the Duchess of Devonshire in 1876. Worth, who was born to Jewish parents in Cambridge, Massachusetts, worked his way up from a bounty jumper during the Civil War (bounty jumpers were those who joined the Army and then deserted with their enlistment bounties), to bank robber, to gambling saloon owner, and finally to jewel and art thief. With his dapper good looks and excellent manners, Worth even managed to infiltrate English high society for a brief period–though of course he used his position to rob his esteemed and flattered aristocratic friends.

In 1875, several members of Worth’s band were arrested at Smyrna, in Asia Minor, on a charge of uttering forged notes. Among the members thus captured were Joe Chapman, Charles Becker and Joe Elliot, all American thieves, who had followed the reluctant Worth into his exile. Always obsessed by the fear of a captured confederate turning State’s evidence, Worth, as he never failed to do in similar cases, moved heaven and earth in his efforts to secure their release from the Turkish prison into which they had been cast. Finally, though it cost him almost the whole of his remaining fortune, Worth succeeded in bribing the jailer and the thieves escaped. They came back to join Worth in London, and there resumed their old business of forging bank paper.

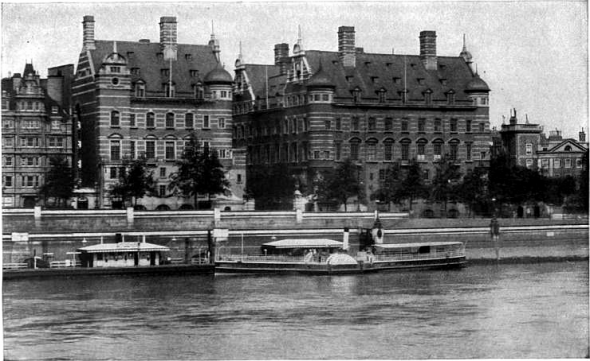

One of them was arrested in Paris on complaint of a swindled bank and was extradited to London, where it again became the first duty of Worth to get the man out of the clutches of the law. But English authorities are of quite a different type from those who rule the prisons of the sultan, and Worth knew the futility of attempting bribes. Moreover he had no money, even if bribery had been possible. It became necessary in some way to secure the release of his confederate under heavy bonds. Then he could cut and run, leaving the bondsman to pay the forfeit. But how should a professional criminal, without funds or friends, secure the signature of a man who would be willing to take the risk and whose responsibility would be accepted by the sharp-eyed English courts?

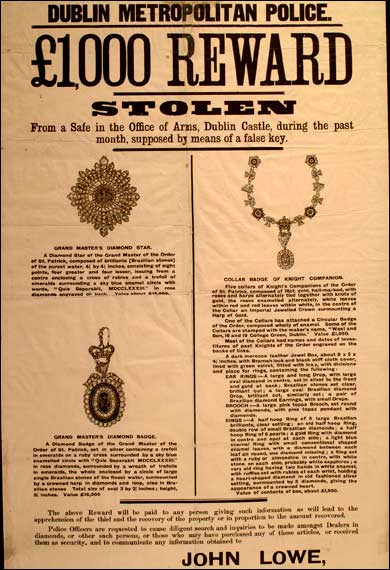

In his flush days, Adam Worth—then as always a lover of the fine arts and something of a connoisseur—had often visited the galleries of the Messrs. Agnew & Co., for many years one of the leading art dealers in London. He had seen hanging on the walls of their galleries a portrait of the Duchess of Devonshire, by Gainsborough, the famous English artist. He knew that the painting was a famous one and was valued by its owners at fifty thousand dollars.

To the cunning mind of Worth, evolving plan after plan for securing a bondsman for his trapped confederate, finally came the idea of stealing this noted canvas from its frame and using it as a lever for getting the necessary signature. His resources were exhausted, his confederates in hiding, his need was instant. He was, in fact, desperate, and he hailed the idea of stealing the masterpiece as an inspiration.

Contrary to his invariable rule, Worth decided to take an active part himself in the actual robbery. It may well have been that his boldest lieutenants were frightened by the sheer audacity of Worth’s plan. At any rate, one dark and rainy night, when a fog fell down over the streets of London, Adam Worth and one confederate, a gigantic thief named Philipps, started out from their lodgings to commit the theft. They crept down Bond Street in the dark, waited until the policeman on the beat had passed them by, then Philipps made a ladder of his broad back and the dapper little Worth climbed up until he was able to reach the stone coping which ran around the front of the gallery. From this, as a standing place, Worth was able to reach a second story window, the sash of which he pried up with a jimmy. Once inside it took him less than a minute to reach the Gainsborough picture, the location of which he had clearly in mind. Lighting a single match to make sure of his prize, he quickly ran a sharp knife through the canvas, close to the edge of the frame, and in an instant the treasured masterpiece was rolled in a tight cylinder, wrapped in a sheet of paper and hidden away under Worth’s coat.

Listening for a moment for a possible signal from Philipps on the outside, Worth quickly mounted to the window and jumped lightly from the coping to the ground.

The negotiations through which Worth hoped to obtain a bondsman for his captured confederate,—using the stolen picture as a lever,—came to nothing. Their only result was to make it fairly certain that the missing Gainsborough was in Worth’s possession. He being an American thief, the Pinkertons were called in to secure, if possible, the return of the picture. They made immediate efforts towards that end, but it was not until twenty-six years later that William A. Pinkerton personally secured the precious bit of canvas in Chicago and turned it over to the representative of the Messrs. Agnew, who had crossed the ocean for the purpose of receiving it.

During the quarter of a century which elapsed between the theft of the picture and its return, it was always in the custody of Worth or hidden away where he alone knew its location. Many times Phillips, who assisted in robbing the Agnew gallery, forced Worth to pay him money under threats of exposure. Once, indeed, he actually told the people most interested, that Worth had stolen the picture, and still had it in his possession. But the crafty Worth had never revealed to anyone the hiding place of the masterpiece, and the employers of the Pinkertons were less anxious to punish the robber than to recover their lost and extremely valuable property. So for some years negotiations went on, Worth using his possession of the Gainsborough picture as a shield against punishment for other crimes.

Finally Pat Sheedy, of international notoriety as a gambler, who had known Worth for years, came to the Pinkertons endowed with all the powers of an ambassador to negotiate terms for the return of the painting. Such terms were finally arranged,— though never made public,—and, at a hotel in Chicago, before the wondering and delighted eyes of the Agnews’ representative, Sheedy finally produced a little metal cylinder, within which was enclosed the canvas, rolled up as it had been on the night of the theft, and none the worse for its long confinement in such narrow space.

Meanwhile, during these long, drawnout negotiations, Worth continued his career of crime. He introduced the American railroad train “hold-up” into South Africa, and succeeded in stealing nearly a million dollars’ worth of diamonds in this way. Then he purchased a steam yacht, and cruised for a time in the Mediterranean, hoping thus to evade the constant demands of his confederates, who hounded him continually with demands for “hush money.” But even a steam yacht did not prove a safe refuge for the King of Criminals. He was forced to sell his “floating palace,” and to engage again in robbery and swindling operations. In Belgium, while attempting the robbery of a mail wagon, he was captured, and sentenced to seven years’ imprisonment.

–“Greatest Detective Agency in the World,” The Strand (1905)

Read more about the extraordinary life of Adam Worth in The Napoleon of Crime: The Life and Times of Adam Worth, Master Thief by Ben Macintyre

Comments are closed.