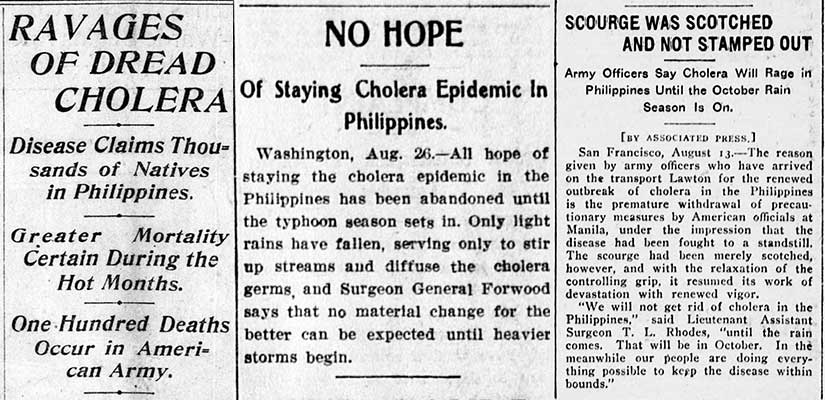

My upcoming novella Tempting Hymn will be the second in my series to mention the 1902 cholera epidemic in the Philippines. The book’s hero, Jonas Vanderburg, volunteered his family for mission work in the Philippines, only to lose his wife and daughters in the same outbreak that Georgina Potter dodged when she arrived in Manila in Under the Sugar Sun. Do I just need a new idea? I would argue that I’m writing about what people feared most in the Edwardian era. Before the mechanical death of the Great War, disease was the worst of the bogeymen.

My books may be historical romance, but this post will not romanticize the history. Census figures put the total death toll from Asiatic cholera in the Philippines (1902-1904) between 100,000 and 200,000 people. Even that number might be low. This strain of the disease was particularly virulent, killing 80 to 90 percent in the hospitals. The disease progressed rapidly and painfully:

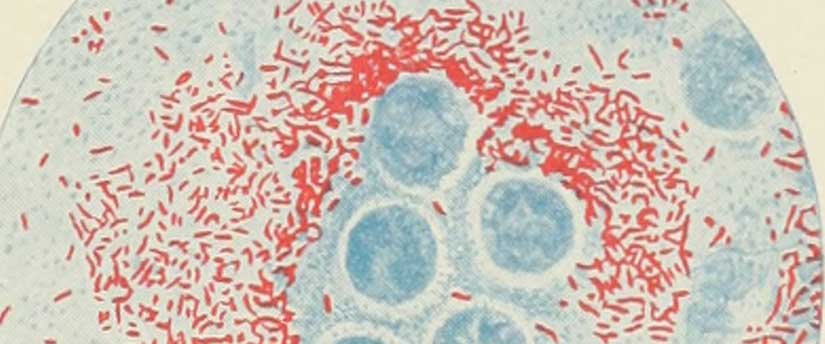

Often the disease appears to start suddenly in the night with a violent diarrhea, the matter discharged being whey-like, ‘rice-water’ stools…Copious vomiting follows, accompanied by severe pain in the pit of the stomach, and agonizing cramps of the feet, legs, and abdominal muscles. The loss of liquid is so great that the blood thickens, the body becomes cold and blue or purple in color…Death often occurs in less than a day, and the disease may prove fatal in less than two hours. (A.V.H. Hartendorp, editor of Philippine Magazine)

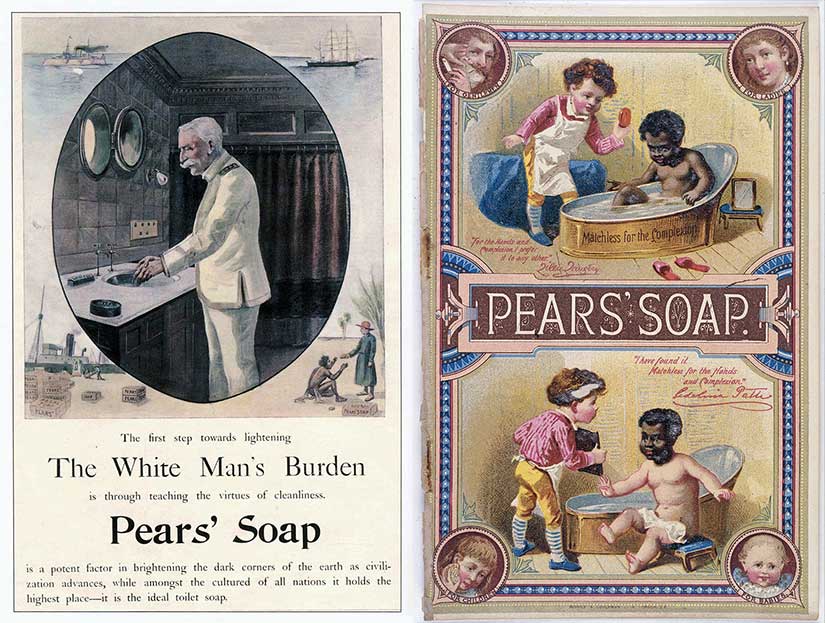

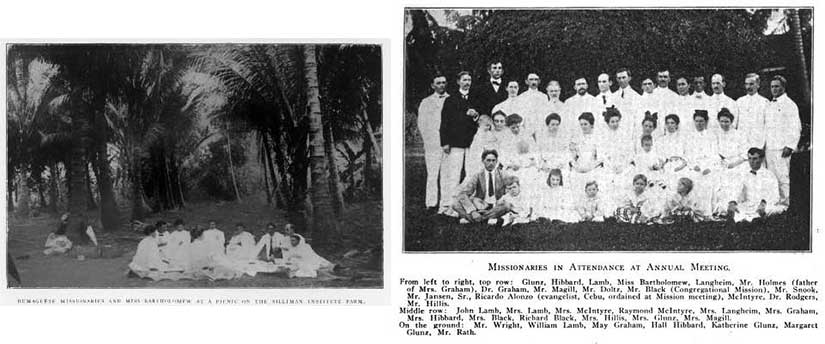

The Yanks saw cholera as a personal challenge to their colonial ideology. They had come to the Philippines to “Fill full the mouth of famine and bid the sickness cease,” in the words of Rudyard Kipling. What was the point of bringing the “blessings of good and stable government upon the people of the Philippine Islands” if they could not prove the value of their civilization with some “modern” medicine?

Cholera was not a new killer in the islands, nor did the Americans bring the disease with them. Though the Eighth and Ninth Infantries were initially blamed, the epidemic had its roots in China. As Ken de Bevoise said in his outstanding work, Agents of Apocalypse: “The volume of traffic…between Hong Kong and Manila in 1902 was so high that it is pointless to try to pinpoint the exact source.” However, just because Americans did not bring cholera does not mean that they are off the hook.

War weakens and disperses a population, leaving it more vulnerable to disease. And the way the war was fought south of Manila in 1902 was particularly brutal. General J. Frederick Bell had set up “protection zones” where all civilians were forced to live in close quarters without access to their homes, farms, and wells. Once cholera hit these zones, there was no escape: 11,000 people died. Even worse, mass starvation forced the general public to ignore the food quarantine, meant to keep tainted vegetables from being sold on the market. The Americans blamed Chinese cabbages for bringing cholera spirilla to the Philippines to begin with, but then gave the people no other choice but to eat (possibly contaminated) contraband to survive.

Inside Manila itself people were also quarantined—not a terrible idea on the face of it. The traditional Filipino home quarantine had worked well in the past: infected homes were marked with a red flag to signal people to stay away while loved ones were cared for. But the Americans thought bigger. They “collected” the infected and brought them to centralized hospitals outside of the city. Hospitals…detention camps…who’s to say? According to De Bevoise, eighty percent of the time, when the patient was dragged out of their home and carted off to this “hospital,” which suspiciously also housed a morgue and crematorium, that was the last their family saw of them. Despite the Manila Times portraying the Santiago Cholera Hospital as a “little haven of rest, rather than a place to be shunned,” and bragging that it was staffed by the “gentle…indefatigable, ever cheerful” Sisters of Mercy, people knew better. They would do anything to keep their family members from being taken there. They fled. They hid their sick. Because cremation was forbidden for Catholics at this time, the Filipinos hid their dead.

And the disease spread.

My book Under the Sugar Sun began with a dramatic house burning scene, where public health officials destroyed an entire neighborhood in the name of sanitation. The road to hell is not just paved with good intentions. It is also littered the corpses of industrious, exuberant, and dogmatic government officials. Any houses found to be infected were burned, “because the nipa hut cannot be properly disinfected,” in the words of one American commissioner’s wife. People were forced to find refuge elsewhere in the city, carrying the disease with them. Because it was such a bad policy, Filipinos thought the American officials must an ulterior motive in the burnings: to drive the poor out of their homes, clear the land, and build their own palaces. The commissioner’s wife, Edith Moses, herself said: “Sometimes, when I think of our rough ways of doing things, I feel an intense pity for these poor people, who are being what we call ‘civilized’ by main force….it seems an act of tyranny worse than that of the Spaniards.”

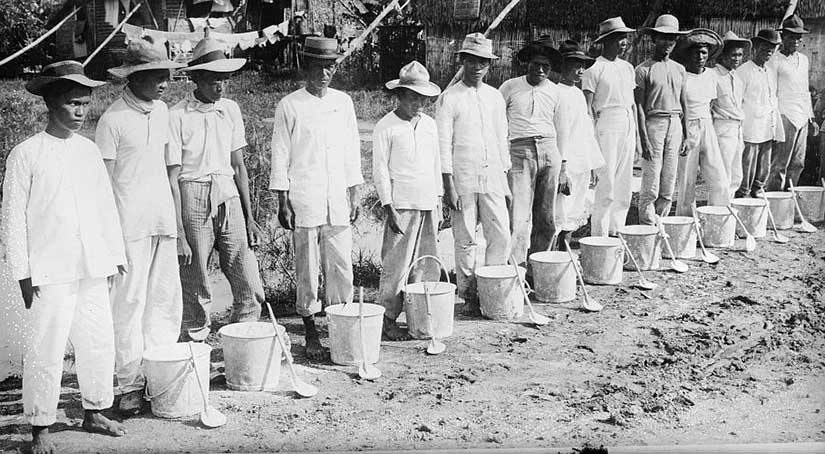

American instructions to the sick were also confusing—and sometimes bizarre. Clean water was a necessity, but this was not something the poor had access to. Commissioner Dean C. Worcester claimed: “Distilled water was furnished gratis to all who would drink it, stations for its distribution being established through the city, supplemented by large water wagons driven through the streets.” But no other source mentions such bounty. In fact, as author Gilda Cordero-Fernando pointed out in her article, “The War on Germs,” in Filipino Heritage, most people treated distilled water like a magic tonic, it was so rare: “Asked whether a certain family was drinking boiled water, as prescribed, one’s reply was ‘Yes, regularly—one teaspoon, three times a day.’” Even worse, though, was this advice by Major Charles Lynch, Surgeon, U.S. Volunteers, which was reprinted in the Manila Times:

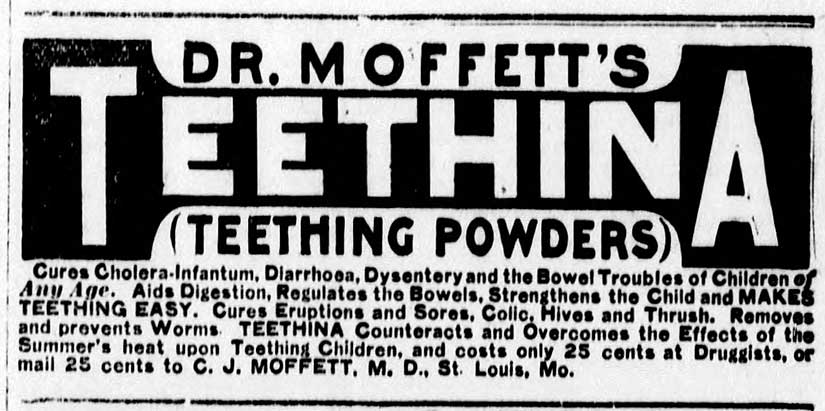

Chlorodyne, or chlorodyne and brandy, have been found especially useful; lead and opium pills, chalk, catechu, dilute sulphuric acid, etc., have all been used. With marked abdominal pain and little diarrhea, morphine should be given…Ice and brandy, or hot coffee, may be given in small quantities, and water, in small sips, may be drunk when they do not appear to increase the vomiting…cocaine and calomel in minute doses—one-third grains—every two hours, having been used with benefit in some cases.

Lead pills. Opium. Morphine. Chalk. Cocaine. And do you know what “calomel” is? Mercurous chloride. If the cholera doesn’t kill you, Dr. Lynch’s treatment will! Though the coffee and brandy sounds nice…

When the Americans could not control the spread of the disease with their ridiculous treatments and counterproductive policies, they blamed the epidemic on the victims. As public health historians Roy M. MacLeod and Milton James Lewis wrote:

American cleanliness was being undermined by Philippine filth. The Manila Times lamented the cholera deaths of “clean-lived Americans.” It identified the “native boy” as “the probable means of infection” since in hotels and houses he prepared and served food and drinks to unwitting Americans. The newspaper reminded its American readers that “cholera germs exude with the sweat through the pores of the [Filipino servant’s] skin” and that “his hands may be teeming with the germs.”

According to the Manila Times, the Americans organized their cholera hospitals by race: the tent line marked street A was “Chinatown,” street B was for the Spanish, street C for white Americans, street D for black Americans, and E through G for Filipinos. Though trade with China had been the cholera vector, Chinese-Filipinos actually had the lowest death rate of any group, including Americans. A Yankee health official ascribed this to the fact that they “eat only long-cooked and very hot food, in individual bowls and with individual chopsticks, and that they drink only hot tea.”

The epidemic reached its peak in Manila in July 1902, and in the provinces in September 1902, before running its course. Its decline was probably due to the heavy rains cleansing the city, increased immunity among the remaining population, and a strategic call by the Archbishop of Manila to encourage Filipinos to bury their dead quickly—but Americans still congratulated themselves on their great efforts. And they had worked hard, it is true: Dr. Franklin A. Meacham, the chief health inspector, and J. L. Judge, superintendent of sanitation in Manila, died from exhaustion. The Commissioner of Public Health, Lt. Col. L. M. Maus, suffered a nervous breakdown. Even the American teachers on summer vacation were encouraged to moonlight as health inspectors—for free, in the end. The wages paid to them by the Police Department were deducted from their vacation salaries because no civil employee was allowed to receive two salaries at once. (The relevant Manila Times article explaining this policy is not online, but its title, “Teachers are Losers” is worth mentioning.)

All their hard work might have been for nought, though. Filipino policies of quarantine would have probably been more effective, had they been given the chance to work. Whipping up the population into a panic was exactly what the Americans should not have done. In the name of containing the disease, they caused the real carriers—people—to disperse wider and faster throughout the country. We all need to be on guard against such hubris, which is why I write my love stories in the middle of strange settings like cholera fires and open insurrections. Come for the sexy times, stay for the political history. Enjoy!

If the total death toll from Asiatic cholera in the Philippines was up to 200,000 people, rampant diseases probably were the most feared crisis in the Edwardian era. But that seems ahistorical. Medieval diseases, starvation and war _were_ expected; Edwardian catastrophes should not have been.

Good on the Archbishop of Manila for encouraging the Filipinos to bury their dead quickly. But how sad that they needed an archbishop to tell them in 1902.

Thanks for the comment, Hels. It does feel like epidemics should not have been so feared in the relatively modern Edwardian era, but then again the “Spanish” influenza pandemic of 1918-1919 killed 50 million people in a single year, more than double the death toll of the Great War. Our state of medicine had improved by the Edwardian era, but it had a ways to go. The descriptions of how to treat cholera are telling…mercury?